Workshop "Digital games through muddled pasts and modded history"

Throughout this two-day event, we will explore the epistemological and political implications that arise from the interweaving of digital games and history. Examining how the decision-making process behind history-themed games is tailored between developers, narrative designers, and historical advisors, we aim to grasp the significance placed on historical representation within the gaming industry. Our guest list includes the narrative director and one of the historians involved in the development of Assassin's Creed: Mirage, which was released in October 2023. Mirage is set in 9th-century Baghdad, and deals with controversial historical subjects such as the memorialisation of the ‘Islamic Golden Age’, the ‘translation movement’ from Greek to Arabic that was patronised by the Abbasid Caliphate, and the Zanj slave rebellion. Additionally, we have invited scholars who have published on different topics connecting digital games and historical motifs, with the aim of stimulating engaged debate among the participants and the wider university community.

The workshop is led by a set of questions concerning the practical and conceptual intricacies of developing and presenting games about historical themes to a global audience:

- How is the decision-making process tailored between developers, concept designers, and historical advisors?

- How are the imageries of medieval or modern conflicts and cross-cultural relationships developed within games?

- In what ways do game mechanics and structures, as well as historical tropes in entertainment software, serve as engagement tools for companies and governments?

- Under which circumstances can play transform into learning about history, and what aspects of gaming defy this shift?

- What are the different implications of digital games for historical knowledge when history is meant to be experienced as a user-oriented medium?

Workshop Programme

Digital games through muddled pasts and modded history

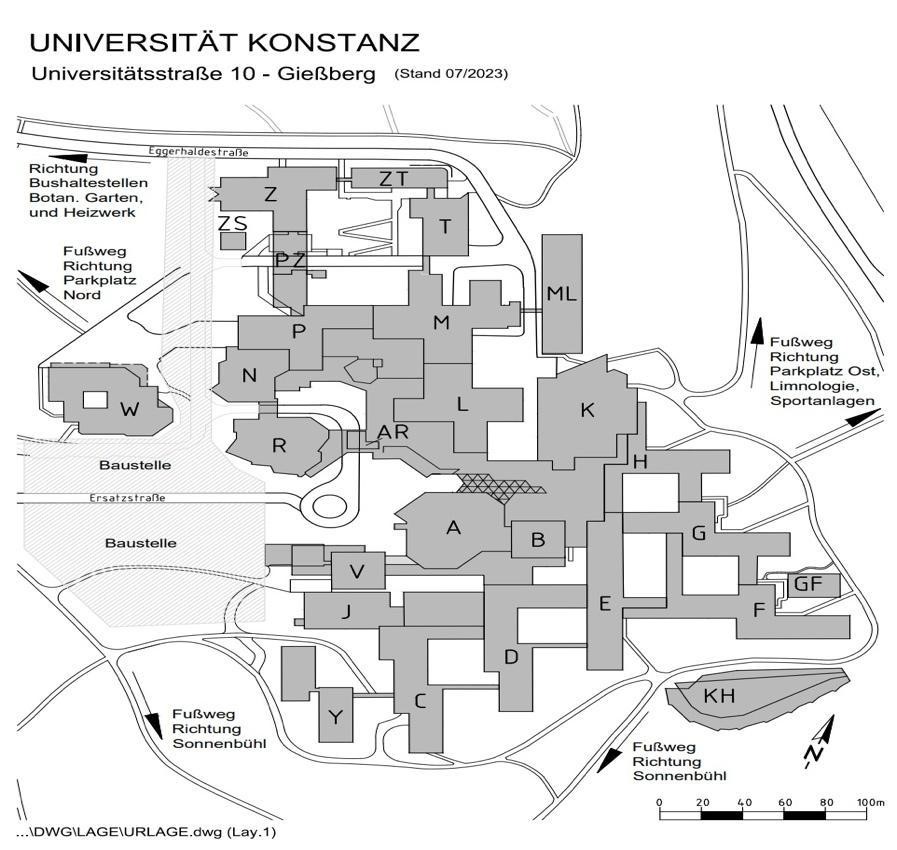

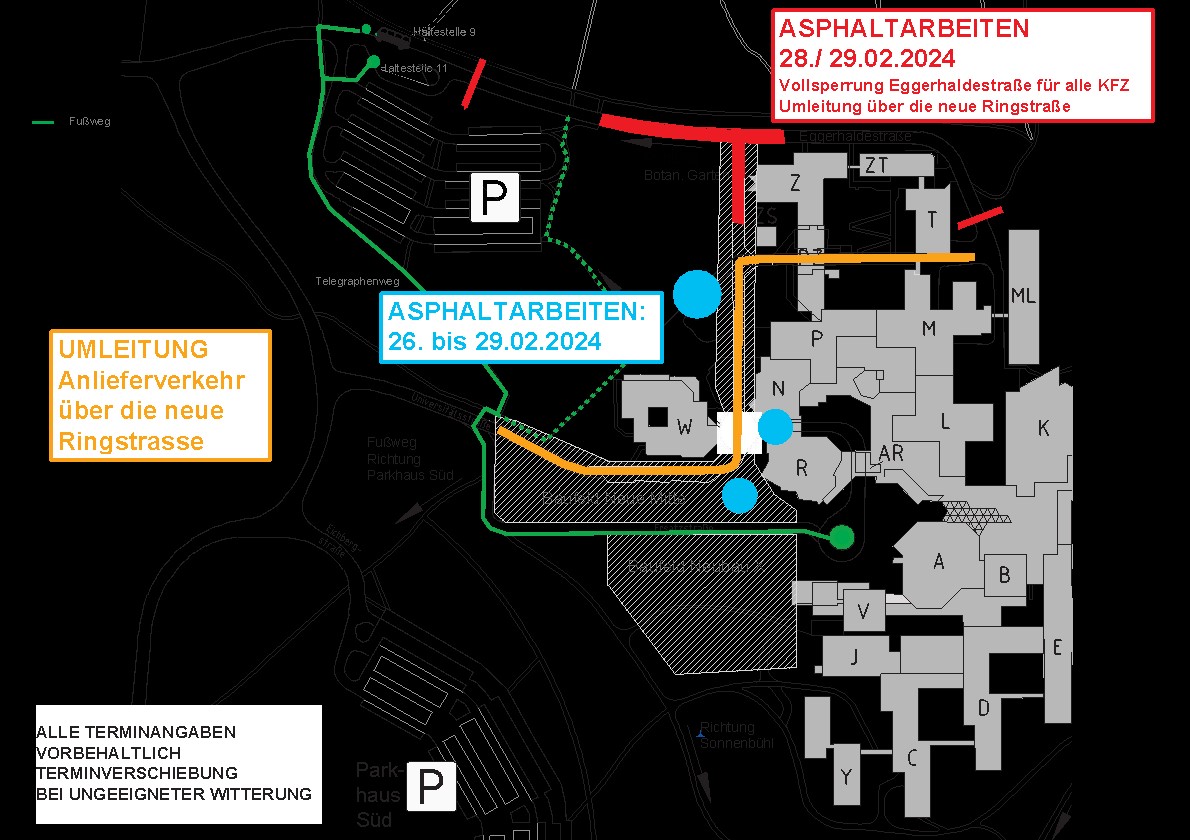

24-25 April 2024, Y 326, Zukunftskolleg

24.04.2024 | OPENING EVENING |

17:00-17:10 CET | Welcome Address at the Zukunftskolleg at the University of Konstanz |

17:10-18:40 CET | Round Table "Presenting the past in Assassin's Creed Mirage" Participants: The round table will deal with the topic of how the Narrative Directors and Historians who recently worked together for the game developer Ubisoft on Assassin’s Creed Mirage (2023) managed to integrate historical content into this hugely popular computer game. The questioning line will involve questions on the representation of historical motifs in games as well as on the ground game production aspects involved in decision-making. Moderated by: |

18:40-19:00 CET | Break |

19:00-20:00 CET | GameLab Session (in situ only) C202 In this session we will have a short, collective gaming session at the GameLab at the University of Konstanz. The GameLab is a facility dedicated to promoting and shaping interdisciplinary research on computer, board and card games as well as ludic initiatives at the university. The core idea of this session is to bring researchers together to exchange ideas on the flight, as they experiment games related to the context of the workshop. |

20:00-20:30 CET | Transfer to restaurant |

20:30 CET | Dinner in Konstanz |

25.04.2024 | WORKING PAPERS* |

10:00-10:15 CET | Coffee reception |

10:15-10:30 CET | Workshop introduction |

10:30-12:15 CET | SESSION A (20 minutes presentations + 15 minutes discussions) 10:30 - James Baillie, Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna: 11:05 - Pedro Panhoca da Silva, Paula Souza State Centre for Technological Education: 11:40 - Ylva Grufstedt, Malmö University: Moderated by: |

12:15-13:15 CET | Lunch |

13:15-15:00 CET | SESSION B (20 minutes presentations + 15 minutes discussions) 13:15 - Robert Houghton, University of Winchester: 13:50 - William Hepburn, University of Aberdeen & Jackson Armstrong, University of Aberdeen: 14:25 - Michael A. Conrad, University of St. Gallen: 15:00 - Jakub Šindelář, Charles University in Prague: Moderated by: |

15:35-15:45 CET | Break |

15:45-16:00 CET | Closing remarks |

*You can find the abstracts below.

Abstracts

“Calculated actions: how game code makes arguments about the past”, James Baillie, Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna

The analysis of history in games often starts with visual and narrative presentations which are some of the clearest representations of historical topics in ludic formats. These are, however, not the only ways through which players of games access ideas about the historical past. Digital games also present implicit arguments about the sorts of pasts we imagine through their code and mechanics, which can both responsively reshape the visual and narrative elements of a game and can provide a representation of processes, dynamics and decision-making in historical and pseudo-historical settings. In settings inspired by history, whether explicitly ‘historical’ or not, these ideas enter a complex space where historical research, popular historiography, modern ideas and ideals, ludic imperatives and the pseudohistorical fantastic can all collide.

This paper will analyse some examples of how access to imagined pasts in game worlds is mediated by computer code, and how it models particular historical processes. The implicit arguments that developers make about their game-worlds can provide key parts of how players intuitively feel historical and pseudo-historical game worlds should work – including but not limited to perceptions of how trade and exchange function, the role of violence in pre-modern societies, or how pre-modern people thought about their world. This feel and the space for interactions in a particular setting embed historiography at the heart of a game’s processes. Players’ ability to access curated selections of historical ideas through games should, therefore, be understood through the reshaping of game spaces around the player that code allows.

Pedro Panhoca da Silva, Paula Souza State Centre for Technological Education

Since their inception, gamebooks have focused on narratives inspired by Tolkenian fantasy. After its culture spread around the world, conquering reader-players from different countries, and the “original” gamebook became a part of other literary genres such as Science Fiction and Horror, an experimental endeavour deserved to be highlighted in the still primitive history of Brazilian gamebooks: the gamebooks of the now defunct publishing house Akritó. With a collection of just two volumes, Renascido (1996) and Espectro (1996), these interactive texts, even though they didn't sell very much at the time, can be the subject of academic study precisely because they offer their readers-players something different from the standard RPG fantasy adventure. By presenting the first title in the collection, Renascido, the aim is to show the potential of gamebooks like this to promote social reflection and contemporary historical studies by combining fantasy with social criticism. This makes these gamebooks, already immersive and interactive by nature, even more attractive by placing their reader-players in everyday situations in the country, as well as meeting the demand of consumers looking for something more than what is normally found in these products.

“The source of wisdom? – Historians’ knowledge and expertise in digital game development", Ylva Grufstedt, Malmö University

Since at least the 1990s, digital game development and marketing has borrowed knowledge and legitimacy from the academic world, for example by hiring historians to carry out research, translation, proofreading as well as design work. This paper explores a few historians' experiences of being employed by game development companies and how notions of popular history and historical culture interplay with scientific expertise. Historians who participate on such terms find themselves in a state of tension between different epistemologies and areas of expertise. That is, historiographical and methodological aspects on history are interjected into a game context which is primarily governed by game development skills and values. This paper highlights how developers as well as historians navigate this tension and what it means for historical as well as game development as fields of knowledge.

The underlying project is an interview study with historians who have fulfilled or currently fulfil such roles, as well as with game developers who hire and engage with them. Through their experiences of influence, agency and limitations, the project seeks answers to questions about whose and which history is in focus, to what extent historian consultants feel that academically situated methodology has a place in this context, and if so how and when, as well as questions about expertise, interdisciplinarity and the notion of the academic historian's relationship to digital popular culture.

“Beyond ‘Press F to Pay Respects’: Accessing History through Empathic Games”, Robert Houghton, University of Winchester

Within the field of Historical Games Studies, roleplaying games, and similar games which engage with their players on a more empathetic level, have often been overlooked. Most research and practical use of games for historical education and engagement has focused on either realist games with high fidelity visuals and engaging stories (such as Assassin’s Creed) or on conceptual games with complex mechanics which can present elaborate historical systems (such as Civilization). Both of these approaches can allow greater accessibility to new and alien periods of history for their players and have been deployed extensively within and outside the classroom.

However, games which deliver their historical engagement by encouraging the player to embody a historical character and experience their world can allow interaction with the past in a very different manner from either realist or conceptual games. By encouraging roleplay or otherwise making the player care for the characters around them, these games can encourage the development of historical empathy and a distinct understanding of the characters and cultures portrayed. These empathetic games offer great potential for education and engagement as a result.

This paper considers the particular qualities of empathetic games such as Papers Please, This War of Mine, and Pentiment. It opens with a discussion of the place of roleplaying and other empathetic games within the realist-conceptual dichotomy described by Chapman before addressing the relative absence of these games within historical game studies. It goes on to argue that empathetic games and empathetic elements within games can play an important role in developing historical understanding and engaging a broader audience.

“Historical primary sources in videogames”, William Hepburn, University of Aberdeen & Jackson Armstrong, University of Aberdeen

The foundation of history as a modern academic discipline is the use of primary sources. Use of such sources, along with secondary sources and clear referencing of both, distinguish academic history amongst other forms of historical practice. The theory and practice of how to incorporate this foundation of academic history into the creation of digital historical games remains underdeveloped in the burgeoning field of historical games studies. As this field has shown, there are many ways a game can be historical, and it need not use or reference primary sources. The contention of this article, however, is that making more transparent reference to primary source material in games is a way in which historians can bring their specialised skills into game development to create compelling experiences for players as well as meet popular demand for historical authenticity in games. Drawing on a survey of historical games and games studies literature, as well as the speakers’ experience making historical games, this paper examines how primary sources have been incorporated and referenced in games and considers other possibilities for doing so. It argues that the use of primary sources in games provides a form of authenticity which increases historians’ potential to use their existing skills to make engaging games and that it better reflects the epistemology of modern historical practice than the positivist theories of history underpinning much of the marketing of authenticity around existing historical games.

“Between Trees and Branches: The Representation of Mediterranean Culture and Cultural Hybridity in Crusader Kings III”, Michael A. Conrad, University of St. Gallen

How to represent the abstract, but nonetheless so very vital, concept of culture is an extremely challenging and difficult task. This is especially true for historical strategy games, given their insurmountable media restrictions that afford to simplify complexity to turn history into a fun and playable experience while at the same time trying to avoid any stereotyping. This danger can be minimized in that historical games do not have to reenact the past but instead offer an experience of alterity that stresses how much history is rooted in contingency.

That said, Crusader Kings III (2020) presumably offers one of the most complex culture systems available in current historical strategy games. The game does not only conceptualize culture as a resource for historical development within a technology tree with path dependencies, which has become a standard since the first edition of the Civilization series (1991). What makes Crusader Kings III stand out is how it adds a further layer of unpredictability by integrating ideas of cultural hybridity and cultural exchange. One of the game’s latest DLCs, Fate of Iberia (2022), whose contents are modelled after the historic power struggle on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages, highlights their important roles for historical development. By comparing its game mechanics with those of other relevant games, such as Civilization, the paper wants to demonstrate how the game offers a more complex historical narrative that acknowledges culture and cultural hybridity as drivers of innovation and change next to research, technology, and war.

“Reception and negotiation of WW1 through digital games by the public(s)”, Jakub Šindelář, Charles University in Prague

When people play and watch others play historical digital games, they are not only passive consumers but can also be considered active actors and co-creators of Public History. This contribution will explore how Public History through WW1 digital games involves the public from three main angles: history for the Public, history with, and by the public. The example of digital games set in WW1 demonstrates why it is important to problematize the singular category of "the public" and look at differences in reception contexts, which warry according to the particular national experience with WW1 and other factors. This period is also an interesting case for being only a relatively recently accepted historical setting for digital games legitimized only around the conflict’s Centenary. There is a significant divergence between the major Western participants like the USA, France, and Germany. Digital game creators sometimes take great care to cater to these differences (Ubisoft Montpellier's Valiant Hearts), sometimes less so, which may result in controversies (EA DICE's Battlefield 1). In detail, the transnational anti-war framing of WW1 in Valiant Hearts as a predominantly (Western) European conflict and the differences between how this framing resonates in different reception contexts. The contribution will also look at possible ways of studying differences in Public negotiation and reception of digital historical games, using multiscalar mixed method approach ranging from auto-ethnography, close reading of paratextually related Let’s Play videos to distant reading using Digital Humanities approaches.