New Zealand

Seitenübersicht

[Ausblenden]1 Country Profile

1.1 General Information

Source: http://www.backpack-newzealand.com/mapofnewzealand.html

Located in the South Pacific Ocean, New Zealand is a remote island nation of around 4.9 million inhabitants. Secluded from its nearest neighbor Australia by a distance of 1600 kilometers, the territory is comprised of two main and a number of small islands. [1] While around three quarters of the population lives on the North Island, the nation in general is divided into two cultural groups: descendants of European immigrants and the native Maori, who are of Polynesian heritage. Economically, the wealthy nation depends primarily on agriculture, but also on manufacturing and tourism. [2]

1.2 New Zealand Politics

Even though New Zealand can formally be classified as a constitutional monarchy, its government functions much like a parliamentary republic. Since 1952, Queen Elizabeth II has been the country’s titular Head of State, represented by Governor-General Dame Patsy Reddy. As of today, the roles of the Head of State as well as the appointed Governor-General are primarily ceremonial. [3]

At the heart of New Zealand’s legislative is the unicameral House of Representatives. Its 120 members are elected for a three-year term through a mixed member proportional system that much resembles Germany’s. Voters can cast an electorate as well as a party vote; while the former is used to directly select a representative in a total of 70 constituencies, the latter determines the total number of party seats. Parties need to receive at least 5% of all votes in order to enter parliament. Appointed by the Governor-General, the Prime Minister traditionally adheres to the strongest party in parliament and is in turn entitled to select the members of cabinet. [4] In 2017, Labour Party Leader Jacinda Ardern was elected the 40th Prime Minister of New Zealand. [5] Her leadership style has been praised internationally as progressive, compassionate and overall extraordinary, especially in the aftermath of the Christchurch killing, during which fifty people were killed at two mosques in a domestic terror attack. [6]

At the heart of New Zealand’s legislative is the unicameral House of Representatives. Its 120 members are elected for a three-year term through a mixed member proportional system that much resembles Germany’s. Voters can cast an electorate as well as a party vote; while the former is used to directly select a representative in a total of 70 constituencies, the latter determines the total number of party seats. Parties need to receive at least 5% of all votes in order to enter parliament. Appointed by the Governor-General, the Prime Minister traditionally adheres to the strongest party in parliament and is in turn entitled to select the members of cabinet. [4] In 2017, Labour Party Leader Jacinda Ardern was elected the 40th Prime Minister of New Zealand. [5] Her leadership style has been praised internationally as progressive, compassionate and overall extraordinary, especially in the aftermath of the Christchurch killing, during which fifty people were killed at two mosques in a domestic terror attack. [6]

2 Preparedness

2.1 Government Structures

Essential in any New Zealand crisis is the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA), an autonomous departmental agency that was established in December of 2019 as a replacement for the Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management. Since then, the Agency is headed by Hon Peeni Henare, Labour Party member and Minister of Civil Defence. [7] Working with central and local government as well as communities and businesses, NEMA aims to “provide strong, national leadership to create an emergency management system that reduces the impact of emergencies”. [8]

In crisis situations, either a local or a national state of emergency can be proclaimed. While the former is managed by regional Civil Defence Emergency Groups (CDEMs), the latter can only be declared by the Minister of Civil Defence.[9] Looking at past states of emergencies, it becomes obvious that New Zealand is mostly affected by natural disasters: from 2002 to 2020, the most common emergencies were floodings, followed by severe weather, earthquakes, landslides and fire. It is also worth noting that the current Covid-19 pandemic is only the second emergency that was declared on a national level during this period of time, after the Christchurch earthquake in 2011.[10]

In crisis situations, either a local or a national state of emergency can be proclaimed. While the former is managed by regional Civil Defence Emergency Groups (CDEMs), the latter can only be declared by the Minister of Civil Defence.[9] Looking at past states of emergencies, it becomes obvious that New Zealand is mostly affected by natural disasters: from 2002 to 2020, the most common emergencies were floodings, followed by severe weather, earthquakes, landslides and fire. It is also worth noting that the current Covid-19 pandemic is only the second emergency that was declared on a national level during this period of time, after the Christchurch earthquake in 2011.[10]

2.2 Health Care System

Another aspect of preparedness is New Zealand’s health care system. Due to government subsidies, health care is affordable – either free or low cost- for the country’s residents and there is a widespread network of doctors in place that is accessible to most.[11] In a ranking among the 24 OECD countries, New Zealand comes in at 19th with a score of 60 out of 100. [12] However, experts such as leading academic Professor Des Gorman have criticized the underfunding of public health units and a shortage of equipment, pointing out that New Zealand only has three intensive care unit beds per 100,000 people, compared to 6.4 in the Netherlands, 11.6 in Switzerland and 12.5 in Bulgaria.[13]

2.3 Global Health Security Index

Source: https://www.ghsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/New-Zealand.pdf

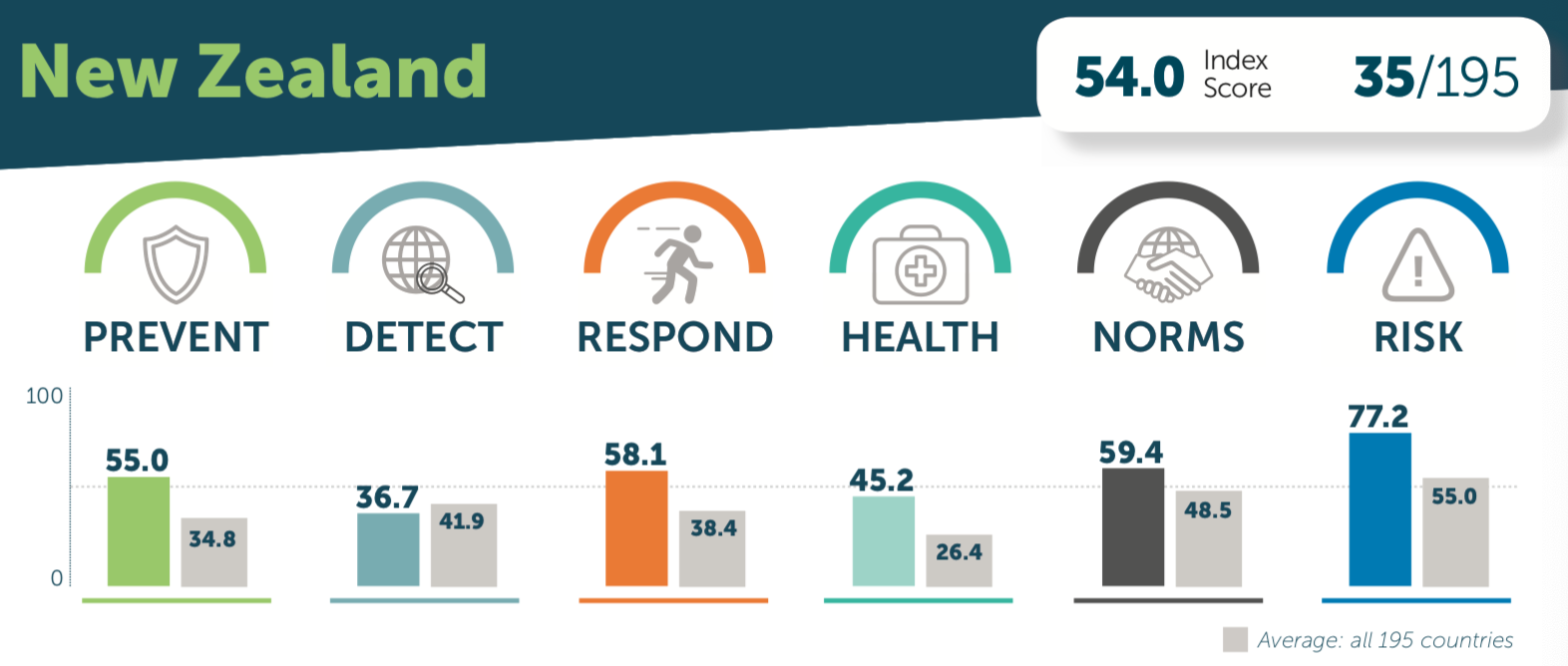

New Zealand’s pandemic preparation can be described as adequate, however it shows some weaknesses in certain areas. According to the 2019 Global Health Security Index, the island nation is among the countries “more prepared” for a pandemic, producing a score of 54 out of 100, which is slightly above the average score of 51.9 for high-income nations. In international comparisons, New Zealand ranks 35th out of 195, below countries such as France, Sweden, Brazil or neighbor Australia. However, both India and Bulgaria have produced lower GHS scores, with 46.5 and 45.6 respectively. [14]

Delving deeper into the GHSI-categories, New Zealand scores particularly low on disease detection and is shown to have a small capacity for real-time surveillance and reporting as well as a frail epidemiology workforce. The latter aspect is particularly concerning, showcasing that the country does not have an effective epidemiology training program available, especially one that is based on international collaboration and cooperation. Additionally, there is no publicly available strategy in place that addresses possible supply shortages of personal protective equipment, and one further weakness concerns the lack of a national disaster risk reduction strategy for pandemics.

That being said, the country does well in emergency preparedness and response planning and exhibits high socio-economic resilience as well as low political and security risk. New Zealand has an effective risk communication system in place, which includes communication protocols that run through social media in order to reach as many people as possible. Both the infrastructure and the health care system have received high scores, and the country meets basic hygienic conditions such as access to sanitation and potable water. Internationally, New Zealand has ratified several conventions that ensure cooperation in case of epidemics and biological attacks, with several cross-border agreements regarding public health emergencies in place. Lastly, there is a special emergency public funding mechanism in place, which is further outlined in the National Health Emergency Plan. [15]

Delving deeper into the GHSI-categories, New Zealand scores particularly low on disease detection and is shown to have a small capacity for real-time surveillance and reporting as well as a frail epidemiology workforce. The latter aspect is particularly concerning, showcasing that the country does not have an effective epidemiology training program available, especially one that is based on international collaboration and cooperation. Additionally, there is no publicly available strategy in place that addresses possible supply shortages of personal protective equipment, and one further weakness concerns the lack of a national disaster risk reduction strategy for pandemics.

That being said, the country does well in emergency preparedness and response planning and exhibits high socio-economic resilience as well as low political and security risk. New Zealand has an effective risk communication system in place, which includes communication protocols that run through social media in order to reach as many people as possible. Both the infrastructure and the health care system have received high scores, and the country meets basic hygienic conditions such as access to sanitation and potable water. Internationally, New Zealand has ratified several conventions that ensure cooperation in case of epidemics and biological attacks, with several cross-border agreements regarding public health emergencies in place. Lastly, there is a special emergency public funding mechanism in place, which is further outlined in the National Health Emergency Plan. [15]

2.4 National Pandemic Plan and Further Aspects

Additional attention can be drawn to New Zealand’s extensive pandemic plan, which has been in place since 2017 and provides guidance in case of large-scale infectious disease outbreaks. Like similar pandemic plans that can be found in Switzerland and Norway, it had originally been created as a preparation for a possible influenza pandemic. However, it can also provide guidance in dealing with other respitory-type pandemics. In general, the New Zealand Influenza Pandemic Plan (NZIPAP) lays out the foundation for the government’s pandemic response with an overarching framework of possible responses that can be adjusted to fit the pandemic’s context. It features an advanced approach to pandemic planning, outlines coordination arrangements and guides through the phases of a pandemic as well as the actions that should follow. Although the course of action for every individual government agency is not specifically addressed in the plan, it nevertheless provides the basis for further detailed response plans. [16]

Further assessment of New Zealand’s pandemic preparedness, tailored specifically to Covid-19 and published at the beginning of Februrary 2020, mentions the National Pandemic Plan as a strength of the country’s response to the looming threat. Highlighting the early travel restrictions for persons coming into the country from China, Prof. Nick Wilson of the University of Otago draws attention to the precautionary approach that was taken by New Zealand’s leaders and praised their sensible cross-party communication. He argues that it is also important to take into account natural advantages: since New Zealand is a remote Pacific Island nation, closing the boarders to foreigners is relatively easy and illegal crossings are largely a non-issue. [17]

Further assessment of New Zealand’s pandemic preparedness, tailored specifically to Covid-19 and published at the beginning of Februrary 2020, mentions the National Pandemic Plan as a strength of the country’s response to the looming threat. Highlighting the early travel restrictions for persons coming into the country from China, Prof. Nick Wilson of the University of Otago draws attention to the precautionary approach that was taken by New Zealand’s leaders and praised their sensible cross-party communication. He argues that it is also important to take into account natural advantages: since New Zealand is a remote Pacific Island nation, closing the boarders to foreigners is relatively easy and illegal crossings are largely a non-issue. [17]

3 Sense-making

3.1 Sense-making Following Boin et al.

The first of five critical tasks of crisis management, Boin et al. (2017) define sense making as “collecting and processing information that will help crisis managers to detect an emerging crisis and understand the significance of what is going on during a crisis”[18] . As a crisis hits, its implications are often impossible to recognize for leaders, which is why gathering, processing and sorting information proves to be vital as a crisis manifests itself. The sense-making process in New Zealand’s Covid-19 occurred contemporaneously as the world tried to navigate the pandemic in its early stages. The country placed its first restrictions on incoming travel from China shortly after the WHO declared the virus a pandemic.

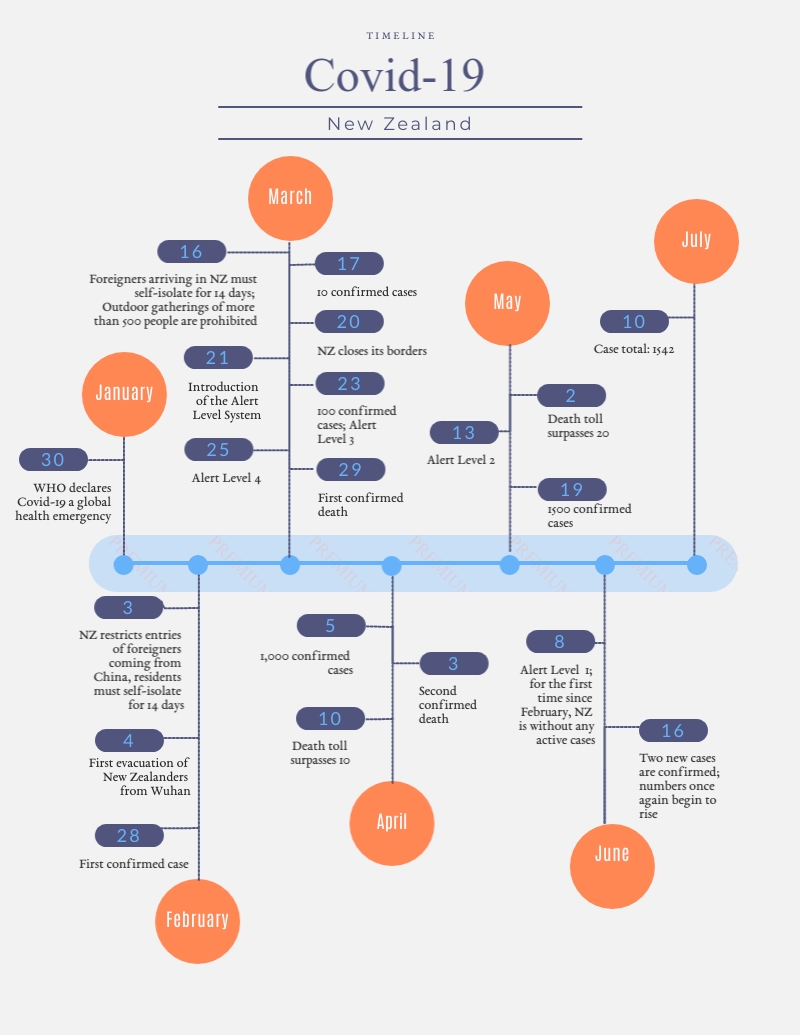

3.2 Brief Timeline of New Zealand's Response

Source: own illustration

3.3 Infections

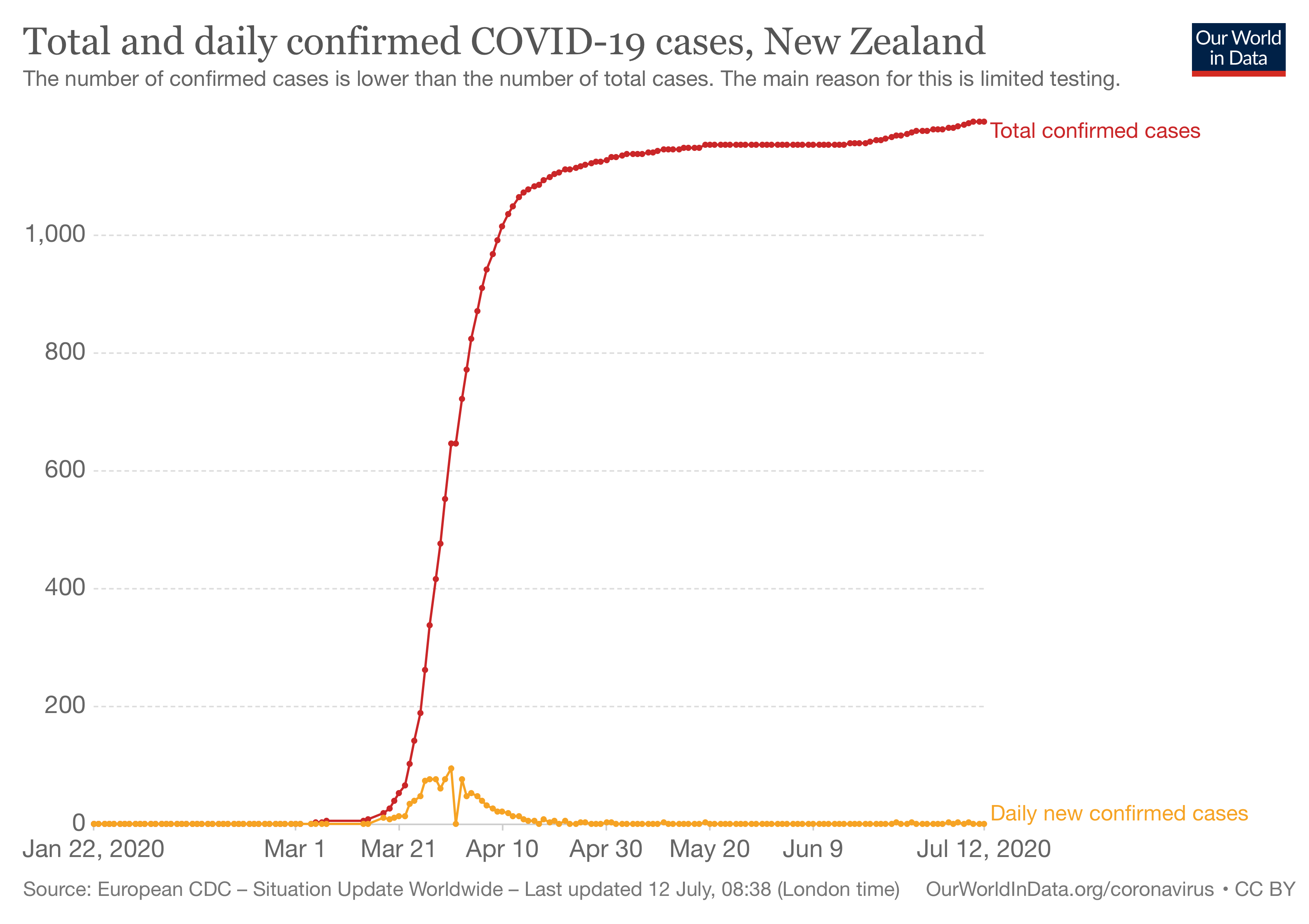

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases?country=~NZLAccess date: 12 July

On 28 February, New Zealand reported its first case of Covid-19, brought to the country by a resident returning from Iran. In mid-March, numbers began to rise with two cases occurring out of Auckland for the first time. On 31 March, New Zealand showed its biggest increase in one day, as 95 new infections are counted. [19] Around the end of April, total and daily cases began to decrease significantly, while on 8 June, the Ministry of Health announced that there were no longer any active cases in the country, for the first time since February 28. On June 16, however, two new cases were brought in from travellers entering New Zealand from the UK, after 24 consecutive days without any new cases. Since then, numbers have once again begun to rise, and as of July 12, there are 25 active cases in the country, with the confirmed number of confirmed and probable cases being 1544. [20]

The biggest age group that has been affected by Covid-19 are persons between the age of 20 and 29, making up 24% of all cases, while females are more likely to contract the virus than men. Almost 70% of cases in New Zealand were imported through international travel or can be closely linked to an overseas acquired case, compared to 30% being locally acquired.[21]

The biggest age group that has been affected by Covid-19 are persons between the age of 20 and 29, making up 24% of all cases, while females are more likely to contract the virus than men. Almost 70% of cases in New Zealand were imported through international travel or can be closely linked to an overseas acquired case, compared to 30% being locally acquired.[21]

3.4 Deaths

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-deaths?country=~NZLAccess date: 12 July

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/mortality-risk-covid?country=~NZL

On 29 March, New Zealand reported its first Covid-related death. Four people in the country died of the virus on 14 April, the most in one day thus far. Since May 28, the government has reported no new deaths, locking in the death toll at 22 in total. [22]

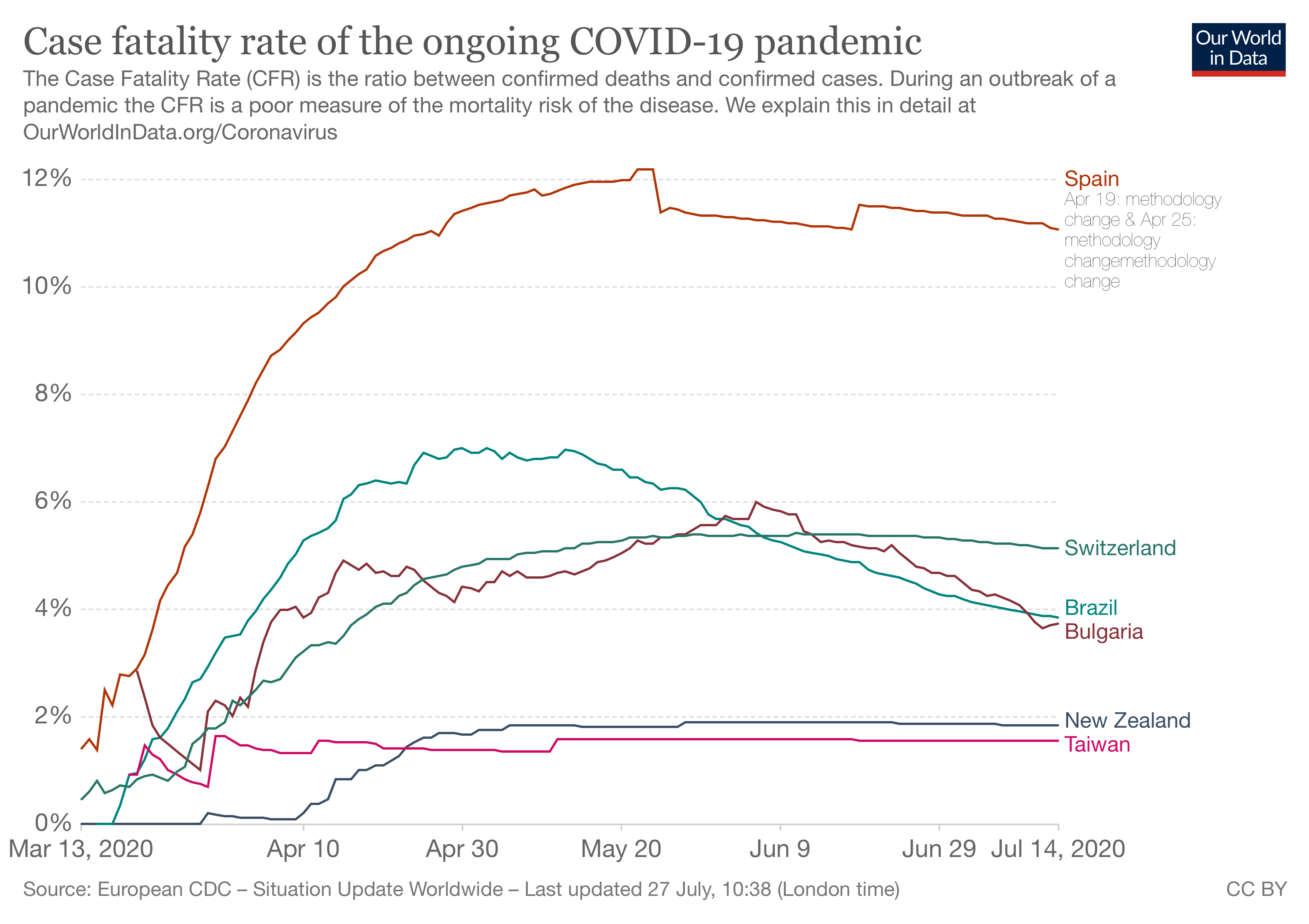

Considering the relatively low death count in New Zealand, the mortality risk of Covid-19 in the country is arguably more interesting. However, it is difficult to obtain reliable information, since we need the number of total cases as well as the final number of deaths. While the former can only be approximated through the number of confirmed cases, the amount of unrecorded cases is difficult to pinpoint. The risk of dying from Covid-19 can be assessed using the case fatality rate, the crude mortality rate and the infection fatality rate, with all of the indicators showing some limitations. Most commonly discussed is the case fatality rate (CFR), which is easily calculated dividing the number of deaths by the number of diagnosed cases. The CFR is important, but provides only limited information, since the total number of cases and deaths would be necessary to obtain the true risk of dying. The crude mortality rate, in turn, measures the likelihood for any individual in the population to die from Covid-19, going beyond the infection rate. Calculated by dividing the number of deaths by the total population, the crude mortality rate can easily be misinterpreted as the case fatality rate. Lastly, and most importantly, the infection fatality rate (IFR) measures the probability of an infected person dying from Covid-19. Dividing the number of deaths by the total number of cases, the IFR would be the most reliable way of looking at the case fatality rate of Covid-19. However, the total number of infections remains unknown, and the quality of its approximation differs widely, depending on the amount of tests processed. [23]

In short, only the CFR can in practice be used to assess the mortality of Covid-19. Looking at data from New Zealand, the case fatality rate has been just under two percent since the end of April, compared to around eleven percent in Spain and five percent in Switzerland. This difference can be attributed to many factors, such as the number of tests processed, the measures put in place by the government, and whether the health care system suffered a collapse.[24]

Considering the relatively low death count in New Zealand, the mortality risk of Covid-19 in the country is arguably more interesting. However, it is difficult to obtain reliable information, since we need the number of total cases as well as the final number of deaths. While the former can only be approximated through the number of confirmed cases, the amount of unrecorded cases is difficult to pinpoint. The risk of dying from Covid-19 can be assessed using the case fatality rate, the crude mortality rate and the infection fatality rate, with all of the indicators showing some limitations. Most commonly discussed is the case fatality rate (CFR), which is easily calculated dividing the number of deaths by the number of diagnosed cases. The CFR is important, but provides only limited information, since the total number of cases and deaths would be necessary to obtain the true risk of dying. The crude mortality rate, in turn, measures the likelihood for any individual in the population to die from Covid-19, going beyond the infection rate. Calculated by dividing the number of deaths by the total population, the crude mortality rate can easily be misinterpreted as the case fatality rate. Lastly, and most importantly, the infection fatality rate (IFR) measures the probability of an infected person dying from Covid-19. Dividing the number of deaths by the total number of cases, the IFR would be the most reliable way of looking at the case fatality rate of Covid-19. However, the total number of infections remains unknown, and the quality of its approximation differs widely, depending on the amount of tests processed. [23]

In short, only the CFR can in practice be used to assess the mortality of Covid-19. Looking at data from New Zealand, the case fatality rate has been just under two percent since the end of April, compared to around eleven percent in Spain and five percent in Switzerland. This difference can be attributed to many factors, such as the number of tests processed, the measures put in place by the government, and whether the health care system suffered a collapse.[24]

3.5 Testing

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-testing#new-zealand

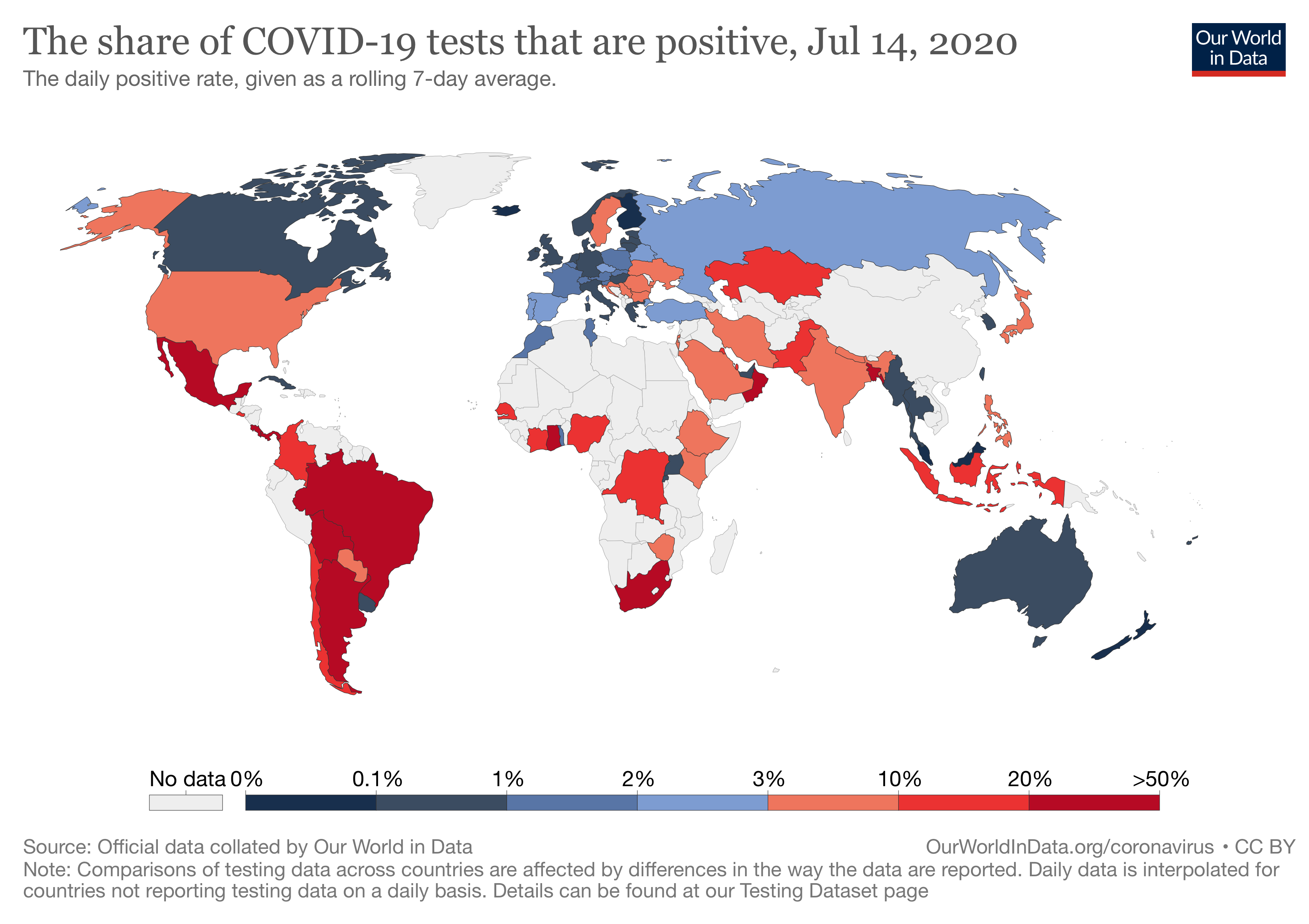

As of 27 June, almost 400 000 tests have been processed. Large-scale testing began around 20 March, during the same time the country closed its boarders and introduced a new Alert Level system. While the Ministry of Health has published data for the total number of tests that have been conducted in New Zealand, the number of people to have been tested is unknown.[25]

At the end of April, the government released its testing approach in Alert Levels 2 and 3. The country follows a local testing approach which involves the twenty District Health Boards responsible for the provision of health care in a certain area.[26] They are instructed to provide testing for every person showing symptoms of Covid-19 as well as close contacts of residents who have tested positive, all while ensuring isolation and quarantine for positive cases. Following this approach, the Ministry of Health sets the following four objectives:

At the end of April, the government released its testing approach in Alert Levels 2 and 3. The country follows a local testing approach which involves the twenty District Health Boards responsible for the provision of health care in a certain area.[26] They are instructed to provide testing for every person showing symptoms of Covid-19 as well as close contacts of residents who have tested positive, all while ensuring isolation and quarantine for positive cases. Following this approach, the Ministry of Health sets the following four objectives:

- Fast identification of all Covid-19 cases, followed by tracing and isolation of contacts

- Equitability of testing for different ethnic groups and in all areas of the country

- Identification of a possible community spread

- Close observation of possible Covid-19 outbreaks among those at high risk of exposure [27]

4 Decision-making

4.1 Decision-making Following Boin et al.

Following once again the definition of Boing et al., decision making and coordinating is defined as “making critical calls on strategic dilemmas and orchestrating a coherent response to implement those decisions”.[29] Decision making in crisis response goes beyond a traditional top-down command process; it requires strategic communication to and throughout crisis networks. A highly centralized state with no regional governments, New Zealand’s central government is largely in charge of the decision making process.[30] Key public figures include the Minister for Civil Defence Peeni Henare, who declared a State of National Emergency on 25 March as well as Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, who is in charge of setting the national Alert Levels. [31] [32] Internationally, the island nation has been praised for its aggressive and pro-active pandemic response, implementing a radical plan that aimed at getting ahead of the virus before it spread beyond control. [33]

4.2 Border Closings

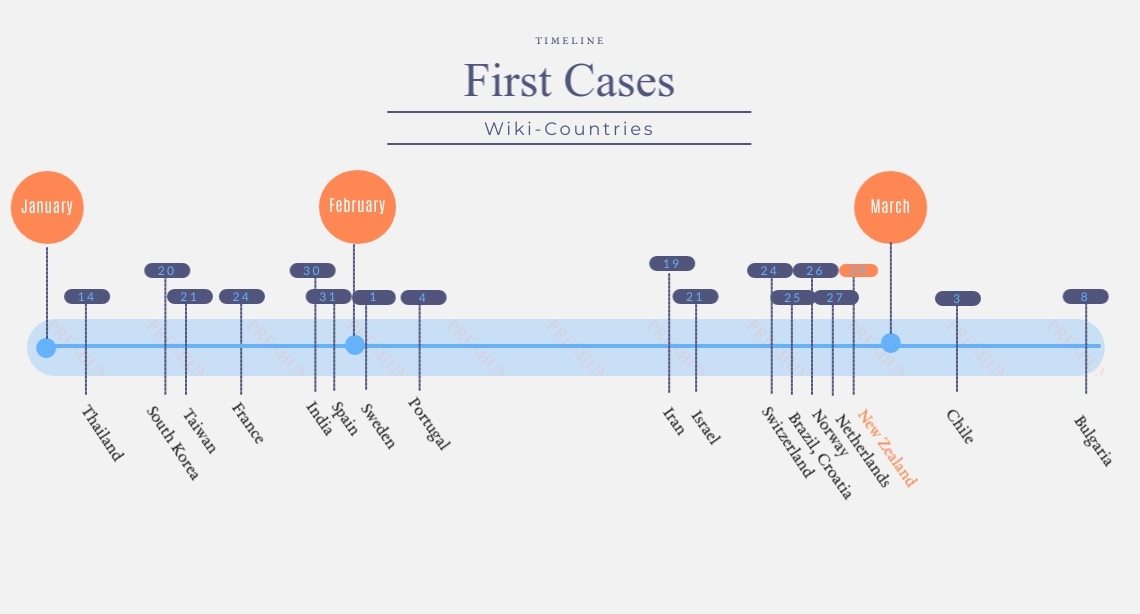

Looking at the timeline of New Zealand’s Covid-19 response, the central government began taking measures aimed at preventing the spread of the virus on 3 February by restricting inbound travel from China, four days after the WHO declared Covid-19 a global health emergency. This decision has been met with praise as well as criticism, with some seeing the gradual boarder closure as an appropriate step considering the nation is largely dependent on tourism, while others argued that border crossings should have come to a complete stop mid-February, not at the end of March. [34] [35] In comparison to other counties, New Zealand closed its borders later than most: Israel, India, Chile and Croatia all took this step up to 8 days before New Zealand did. However in Thailand, another country whose economy heavily relies on tourism, travel came to a stop almost a week later, on March 26.

4.3 Alert System

Central to New Zealand’s pandemic response plan is the newly developed Covid-19 Alert system that was introduced on 20 March. Consisting of four different Alert Levels, the plan provides concise and comprehensive information about the current risk and the arising restrictions to the country’s population. Over the course of the pandemic, the different levels have exclusively come into force on a national scale, but can in theory also be applied at the regional or local level following an outbreak of the virus that is limited to a certain geographical area.

- At Alert Level 1, Covid-19 is contained on a national level, but remains uncontrolled overseas. Measures range from extensive travel restrictions to large-scale testing for the virus, while contact tracing takes place and individuals tested positive or showing symptoms are placed in quarantine. However, schools and workplaces are open and operate as usual, while all restrictions on domestic transport, personal movement and gatherings are lifted.

- At Alert Level 2, the virus is contained in New Zealand, with a remaining risk of community transmission and cluster outbreaks. Businesses are required to follow public health guidance and a physical distance of two meters between individuals in public places is in order. Gatherings are restricted to 100 people, and those at risk for a severe disease progression are advised to take additional precautions.

- At Alert Level 3, the disease is likely not contained, while community transmissions and outbreak clusters may occur. People are instructed to work from home whenever possible, while schools operate at limited capacity and public venues are closed. Contact between individuals is limited to their immediate household and close family members, and gatherings of up to ten people are allowed exclusively for wedding and funeral services. Public movement is severely restricted, and especially inter-regional travel remains largely exclusive to essential workers.

- At Alert Level 4, the disease is not contained, with community transmission and widespread cluster outbreaks taking place and the country moves to a complete lockdown. The population is instructed to stay at home unless personal movement is essential, and traveling is severely limited. Gatherings are prohibited and public venues, non-essential businesses and educational facilities are closed. [36]

4.4 Economic Response

Charged with the task of considering the economic implications of the Covid-19 crisis is the New Zealand Treasury, a central agency that serves as the government’s primary advisor for economic and financial matters.[41] The Treasury has set three central goals for New Zealand’s economic response, namely to

In May, the 2020 budget was delivered by the Minister of Finance, taking Covid-19 into particular consideration. Through the establishment of the $50 billion Covid-19 Response and Recovery Fund (CRRF), public services are expected to rebuild from this crisis situation.[44]

- “cushion the financial blow to (…) families, workers, businesses and communities form the impacts of COVID-19

- Position New Zealand for recovery, and

- Reset and rebuild our economy”[42]

In May, the 2020 budget was delivered by the Minister of Finance, taking Covid-19 into particular consideration. Through the establishment of the $50 billion Covid-19 Response and Recovery Fund (CRRF), public services are expected to rebuild from this crisis situation.[44]

4.5 The NZ COVID Tracer App

On 20 May, the Ministry of Health released its NZ COVID tracer app.[45] The application encourages users to create a digital diary, recording the places they visited by scanning official QR codes that are placed in public buildings, stores and shops. As an alternative, it is also possible to add a manual entry, which is especially useful for private visits to individuals where a QR code is not available. By manually contacting users that came into contact with an infected person and asking them to share their complete digital diary information, the government aims for a more efficient contact tracing through quickly identifying and isolating anyone who came in contact with Covid-19.[46]

As of July 7, the NZ COVID tracer has 590 000 registered users, thus around 11.7% of the population has downloaded the app. Meanwhile, active use reached its peak while the country was at Alert Level 2, with 50 000 daily poster scans. This number has gone down significantly, and as of July 7, only 10 000 scans are made on average every day. This translates to only 0.2% of the population making regular use of the app. Leading experts are concerned about this development, recognizing the opportunity to actively include the population in the contact tracing process, while at the same time warning that such small usage numbers will hardly make any difference in preventing and detecting community outbreaks.[47]

Similar apps in other countries are technologically more advanced, such as the contact tracing apps in Israel and South Korea, as well as the Aarogya Setu App in India. The latter uses Bluetooth based contact tracing, thus reducing the effort it takes to use the app. This can also be observed in the number of users: In India, the app had 114 million downloads at the end of May and has helped to identify over 3500 hotspots.

As of July 7, the NZ COVID tracer has 590 000 registered users, thus around 11.7% of the population has downloaded the app. Meanwhile, active use reached its peak while the country was at Alert Level 2, with 50 000 daily poster scans. This number has gone down significantly, and as of July 7, only 10 000 scans are made on average every day. This translates to only 0.2% of the population making regular use of the app. Leading experts are concerned about this development, recognizing the opportunity to actively include the population in the contact tracing process, while at the same time warning that such small usage numbers will hardly make any difference in preventing and detecting community outbreaks.[47]

Similar apps in other countries are technologically more advanced, such as the contact tracing apps in Israel and South Korea, as well as the Aarogya Setu App in India. The latter uses Bluetooth based contact tracing, thus reducing the effort it takes to use the app. This can also be observed in the number of users: In India, the app had 114 million downloads at the end of May and has helped to identify over 3500 hotspots.

5 Meaning-making

5.1 Meaning-making Following Boin et al.

We define meaning making as “the attempt to reduce public and political uncertainty and inspire confidence in crisis leaders by formulating and imposing a convincing narrative” (Boin et al. 2017, 79) [48] . This process consists of two steps: Firstly, a persuasive message must be formulated in order to explain the nature, unfolding and repercussions of a crisis, and secondly, said narrative needs to be delivered to the public. Key figures in this process are polical actors, the mass media, and the citizenry.

5.2 Political Leadership

In the political arena, crisis communication in New Zealand’s Covid-19 management largely went through Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, who addressed the nation multiple times during the different stages of the pandemic. As the country closed its borders mid-march, Ardern appealed to the nation to “go hard and go early” [49] , introducing a six-week period of harsh social distancing measures that cumulated in an almost complete lockdown that lasted for over a month.

Looking at a theoretical framework for leader communication strategies, Mayfield & Mayfield (2002) have established a strategy-based model that identifies “direction giving”, “meaning-making” and “empathy” as three key aspects that can increase follower’s trust and loyalty.[50] In the first dimension, Ardern and her government provided very effective crisis communication ranging from government statements, press conferences and speeches to emergency text messages that were delivered to all residents. This direction-giving approach provided very comprehensive information about the current state of affairs and steps to take in the following weeks. Framing the necessary adherence to social distancing measures as a sacrifice taking for the greater good – “stay home and save lives” [51] – Ardern offered a convincing meaning-making narrative to New Zealand’s citizens. Taking it one step further, the PM relied on various unconventional channels of information, spending more than 30 minutes a day online, checking in on New Zealanders via live streams and social media posts and holding a special Covid-19 press conference meant for children and the questions they had concerning the pandemic. [52] [53] In freely acknowledging the struggles Covid-19 has put on the country’s residents, from unemployment, isolation and loss of loved ones to an overall feeling of overwhelmingness, Ardern plays directly into the empathy – dimension of Mayfield & Mayfield’s model.[54]

That being said, the perception of Ardern as an almost infallible example of crisis leadership took a hit when two new cases emerged on June 16 after 24 days with no new infections had passed. While the PM had previously declared that New Zealand had “won the battle”[55] against community transmission of the virus, her optimistic tone shifted a few weeks later as she dubbed the emergence of new cases as “an unacceptable failure of the system” [56] . Slightly shifting from her empathetic narrative to a more vigorous stance, Ardern announced the suspension of the so called “compassionate exemptions” that allowed individuals to leave isolation in urgent situations, such as death of a family member.

Looking at a theoretical framework for leader communication strategies, Mayfield & Mayfield (2002) have established a strategy-based model that identifies “direction giving”, “meaning-making” and “empathy” as three key aspects that can increase follower’s trust and loyalty.[50] In the first dimension, Ardern and her government provided very effective crisis communication ranging from government statements, press conferences and speeches to emergency text messages that were delivered to all residents. This direction-giving approach provided very comprehensive information about the current state of affairs and steps to take in the following weeks. Framing the necessary adherence to social distancing measures as a sacrifice taking for the greater good – “stay home and save lives” [51] – Ardern offered a convincing meaning-making narrative to New Zealand’s citizens. Taking it one step further, the PM relied on various unconventional channels of information, spending more than 30 minutes a day online, checking in on New Zealanders via live streams and social media posts and holding a special Covid-19 press conference meant for children and the questions they had concerning the pandemic. [52] [53] In freely acknowledging the struggles Covid-19 has put on the country’s residents, from unemployment, isolation and loss of loved ones to an overall feeling of overwhelmingness, Ardern plays directly into the empathy – dimension of Mayfield & Mayfield’s model.[54]

That being said, the perception of Ardern as an almost infallible example of crisis leadership took a hit when two new cases emerged on June 16 after 24 days with no new infections had passed. While the PM had previously declared that New Zealand had “won the battle”[55] against community transmission of the virus, her optimistic tone shifted a few weeks later as she dubbed the emergence of new cases as “an unacceptable failure of the system” [56] . Slightly shifting from her empathetic narrative to a more vigorous stance, Ardern announced the suspension of the so called “compassionate exemptions” that allowed individuals to leave isolation in urgent situations, such as death of a family member.

5.3 The Media

According to Boin et al. (2017), the media plays a central role in the meaning-making process of crisis management. Through varying focus, tone and wording, journalists contribute a large part to the framing of any crisis, and are able to strengthen or weaken any organization’s position. In recent years, as news have started to shift from a print to an online format, the role of social media has become increasingly important.[57]

New Zealand has been overwhelmingly present on social media platforms and in international news, with many sources praising its management of the pandemic as the golden standard that other countries should follow. Attributing the country’s success in fighting the virus to a vigilant lockdown, geographic conditions and widespread testing, many news outlets have additionally singled out Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern as a role model of leadership. [58] However, some argue that the nation’s media presence might be too high: While some non-western countries such as Taiwan have not enjoyed similar coverage despite recording even lower transmission and death rates, New Zealand’s strategy has received disproportionate attention.[59]

New Zealand has been overwhelmingly present on social media platforms and in international news, with many sources praising its management of the pandemic as the golden standard that other countries should follow. Attributing the country’s success in fighting the virus to a vigilant lockdown, geographic conditions and widespread testing, many news outlets have additionally singled out Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern as a role model of leadership. [58] However, some argue that the nation’s media presence might be too high: While some non-western countries such as Taiwan have not enjoyed similar coverage despite recording even lower transmission and death rates, New Zealand’s strategy has received disproportionate attention.[59]

6 Legitimacy

6.1 Public Opinion

Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, New Zealand’s crisis management approach has enjoyed considerable approval among its population. According to a leaked poll conducted by UMR at the end of April, 92% of respondents supported the strict measures previously taken as the country moved into Alert Level 2. [60] Currently in charge of governing the country, the Labour Party has reached a 55% approval rating, leaving it at a considerable advantage for the upcoming election this September over the opposing National party, whose ratings dropped to 29%. The cleavage between the two parties becomes even more apparent when looking at their leaders’ approval ratings: while Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern enjoys the support of 65% of respondents, National Party leader Simon Bridges lags behind at only 7%.[61]

However, these numbers are to be taken with a grain of salt. UMR itself stressed the importance of a nuanced interpretation of the results, explaining that while governments’ approval ratings usually benefit from natural disasters, this effect is usually short-lived and wears off quickly. [62]

While I was unable to find a representative survey that gives a detailed overlook over public attitudes toward the government, public health expert Nick Wilson has praised the government for ensuring clear and transparent communication with New Zealand’s residents. Prime Minister Ardern in particular was said to have evoked high levels of public trust, inter alia by cutting her own and other top government officials’ salaries by 20%. Furthermore, Wilson drew particular attention to the fact that New Zealand’s decision-making process was largely guided by expert opinion, while potential political gains and losses for government and opposition were of smaller importance.[63]

Considering implicit clues for public opinion towards New Zealand’s crisis management, the behavioral changes of the residents recorded during the four-week lockdown indicate a high compliance with the imposed Covid-19 measures. A research team from Otago University evaluated Google data in order to track mobility reduction, finding that overall mobility had dropped by 73% at the end of March compared to the baseline data from a five-week period from early January to early February. As Alert Level 4 came into effect, citizens exhibited a high level of behavior change, with workplace movement being reduced by 57% and retail and recreation activities by 90%, which in all likelihood contributed to the levelling of active cases by around April 6. [64]

However, these numbers are to be taken with a grain of salt. UMR itself stressed the importance of a nuanced interpretation of the results, explaining that while governments’ approval ratings usually benefit from natural disasters, this effect is usually short-lived and wears off quickly. [62]

While I was unable to find a representative survey that gives a detailed overlook over public attitudes toward the government, public health expert Nick Wilson has praised the government for ensuring clear and transparent communication with New Zealand’s residents. Prime Minister Ardern in particular was said to have evoked high levels of public trust, inter alia by cutting her own and other top government officials’ salaries by 20%. Furthermore, Wilson drew particular attention to the fact that New Zealand’s decision-making process was largely guided by expert opinion, while potential political gains and losses for government and opposition were of smaller importance.[63]

Considering implicit clues for public opinion towards New Zealand’s crisis management, the behavioral changes of the residents recorded during the four-week lockdown indicate a high compliance with the imposed Covid-19 measures. A research team from Otago University evaluated Google data in order to track mobility reduction, finding that overall mobility had dropped by 73% at the end of March compared to the baseline data from a five-week period from early January to early February. As Alert Level 4 came into effect, citizens exhibited a high level of behavior change, with workplace movement being reduced by 57% and retail and recreation activities by 90%, which in all likelihood contributed to the levelling of active cases by around April 6. [64]

6.2 Accountability, Transparency and Opposition Concerns

The New Zealand government has taken several extraordinary measures in order to effectively prevent the spread of Covid-19. In March 2020, the virus was added to the Health Act of 1956, classifying it as a ‘quarantinable disease’ and broadening the scope of action concerning border closures, isolation of individuals and the introduction of the Alert system. By declaring a state of emergency under the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act of 2002, the Director of Civil Defence was given the power to limit access to roads and public places, evacuate premises and provide food, shelter and other first aid measures to the residents. [65] Under general legislation, judges were allowed to modify rules of court to adapt to the situation, and on March 25, Parliament decided to pass two additional laws that aimed at protecting tenants at risk of eviction and enabled the arrangement of virtual meetings in educational facilities and local governments. The same day, Parliament adjourned for over a month until the end of April. [66]

The New Zealand government ensured accountability and transparency in various ways. At the end of March, the government motioned to establish and Epidemic Response Committee in Parliament to keep an eye the government’s crisis management approach. Most importantly, the committee is led by the opposition and chaired by Simon Bridges, Leader of the National Party, and has far-reaching power to subpoena documents, persons and records. While several opposition politicians have criticized the decision to adjourn Parliament at the end of March, arguing that the emergency powers of the government went too far, the establishment of the committee as the principal mechanism for political accountability has received bipartisan support.[67] As far as transparency is concerned, the government published its actions as well as the legal foundations for the measures that were implemented in a comprehensive manner online.[68] Furthermore, leaders and key officials held daily briefings, especially at the beginning of the Covid-19 outbreak, formulating their messages in a clear and concise way while leaving considerable time for questions from journalists.[69]

The New Zealand government ensured accountability and transparency in various ways. At the end of March, the government motioned to establish and Epidemic Response Committee in Parliament to keep an eye the government’s crisis management approach. Most importantly, the committee is led by the opposition and chaired by Simon Bridges, Leader of the National Party, and has far-reaching power to subpoena documents, persons and records. While several opposition politicians have criticized the decision to adjourn Parliament at the end of March, arguing that the emergency powers of the government went too far, the establishment of the committee as the principal mechanism for political accountability has received bipartisan support.[67] As far as transparency is concerned, the government published its actions as well as the legal foundations for the measures that were implemented in a comprehensive manner online.[68] Furthermore, leaders and key officials held daily briefings, especially at the beginning of the Covid-19 outbreak, formulating their messages in a clear and concise way while leaving considerable time for questions from journalists.[69]

7 Overall Evaluation

Source: own illustration

Boin et al. (2017) identify threat, urgency and uncertainty as major characteristics of any crisis. Given the threat of the coronavirus, which manifests itself through potentially severe symptoms and a global mortality rate of around 3-4%, nations worldwide were faced with the urgency of containing the virus as well as possible, and the uncertainty of how the pandemic would progress. [70]

While a complete evaluation of New Zealand’s crisis management won’t be possible until the Covid-19 pandemic is over, some valuable lessons can already be drawn from the country’s strategies.

New Zealand recorded its first case on February 28, which was rather late in international comparison. While other countries were hit by the pandemic soon after it emerged, New Zealand had more time to assess the development overseas, and by the time community transmission started to occur, there was already a good amount of awareness about the severity of the situation. Nevertheless, the country closed its borders later than other nations, a decision which may be linked to the high economic dependence on tourism.

Several international media outlets have praised the country’s leadership for its clear-cut, comprehensive and empathetic crisis communication, and similar tendencies can be observed among the nation’s residents. The government has managed to get citizens to comply

with the strict lockdown that was the centerpiece of New Zealand’s pandemic response and brought many aspects of public life to a complete stop. The country’s pro-active, preventative approach manifests itself in a low infection rate and a marginal death toll.

However, large parts of the nation’s success can be attributed to its favorable geographical features; most notably its low population density, remoteness and easily sealable borders. Considering the fact that these conditions cannot be replicated by other nations looking for an good response strategy, one might do better to look at Taiwan as a more realistic example of effective crisis management: Despite its close proximity to China, the country has managed to keep numbers to a minimal level through the extensive use of technology for case identification and subsequent quarantining, and its contact-tracing methods proved to be very effective, aside from emerging privacy concerns.

In my personal opinion, the major takeaway from New Zealand’s crisis management response is the futile notion of “eradicating” the virus through social distancing measures alone. Even though the country managed to keep the infection rate at zero for over three weeks, the pandemic came to a pause rather than a full stop, and numbers continued to rise again. Covid-19 remains ongoing in most parts of the world, and until there is a vaccine or a general immunity among the population it will not be defeated.

While a complete evaluation of New Zealand’s crisis management won’t be possible until the Covid-19 pandemic is over, some valuable lessons can already be drawn from the country’s strategies.

New Zealand recorded its first case on February 28, which was rather late in international comparison. While other countries were hit by the pandemic soon after it emerged, New Zealand had more time to assess the development overseas, and by the time community transmission started to occur, there was already a good amount of awareness about the severity of the situation. Nevertheless, the country closed its borders later than other nations, a decision which may be linked to the high economic dependence on tourism.

Several international media outlets have praised the country’s leadership for its clear-cut, comprehensive and empathetic crisis communication, and similar tendencies can be observed among the nation’s residents. The government has managed to get citizens to comply

with the strict lockdown that was the centerpiece of New Zealand’s pandemic response and brought many aspects of public life to a complete stop. The country’s pro-active, preventative approach manifests itself in a low infection rate and a marginal death toll.

However, large parts of the nation’s success can be attributed to its favorable geographical features; most notably its low population density, remoteness and easily sealable borders. Considering the fact that these conditions cannot be replicated by other nations looking for an good response strategy, one might do better to look at Taiwan as a more realistic example of effective crisis management: Despite its close proximity to China, the country has managed to keep numbers to a minimal level through the extensive use of technology for case identification and subsequent quarantining, and its contact-tracing methods proved to be very effective, aside from emerging privacy concerns.

In my personal opinion, the major takeaway from New Zealand’s crisis management response is the futile notion of “eradicating” the virus through social distancing measures alone. Even though the country managed to keep the infection rate at zero for over three weeks, the pandemic came to a pause rather than a full stop, and numbers continued to rise again. Covid-19 remains ongoing in most parts of the world, and until there is a vaccine or a general immunity among the population it will not be defeated.

8 Country's favourite stay at home song

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rVhd21jpjGQ

[1] Conrad, Keith, Alexander Blyth, Warren Moran, Raewyn Dalziel, William Hosking Oliver and Jack Vowles. 2020. „New Zealand“ Britannica, June 12 2020. https://www.britannica.com/place/New-Zealand

Access date: 15 June

Access date: 15 June

[2]

New Zealand Country Profile“ BBC News, June 8 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-15357770

Access date: 15 June

New Zealand Country Profile“ BBC News, June 8 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-15357770

Access date: 15 June

[3] „Frequently Asked Questions“ New Zealand Republic. http://www.republic.org.nz/faqs

Access date: 15 June

Access date: 15 June

[4] „New Zealand: Constitution and politics“ The Commonwealth. https://thecommonwealth.org/our-member-countries/new-zealand/constitution-politics

Access date: 15 June

Access date: 15 June

[5] „RT Hon Jacinda Ardern“ New Zealand Labour Party. https://www.labour.org.nz/jacindaardern

Access date: 16 June

Access date: 16 June

[6] Lester, Amelia. 2019. „The Roots of Jacinda Ardern’s Extraordinary Leadership after Christchurch“ The New Yorker March 23 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/what-jacinda-arderns-leadership-means-to-new-zealand-and-to-the-world

Access date: 16 June

Access date: 16 June

[7] „Hon Peeni Henare“ New Zealand Parliament, May 15 2020. https://www.parliament.nz/en/mps-and-electorates/members-of-parliament/henare-peeni/

Access date: 19 June

Access date: 19 June

[8] „National Emergency Management Agency“ New Zealand Government, June 19 2020. https://www.govt.nz/organisations/national-emergency-management-agency/

Access date: 19 June

Access date: 19 June

[9] „Who does what in an emergency“ Get Ready New Zealand https://getready.govt.nz/emergency/who-does-what-in-an-emergency/

Access date: 19 June

Access date: 19 June

[10] „Declared States of Emergency“ National Emergency Management Agency https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/resources/previous-emergencies/declared-states-of-emergency/

Access date: 19 June

Access date: 19 June

[11] „Healthcare“ New Zealand Now https://www.newzealandnow.govt.nz/living-in-nz/healthcare

Access date: 20 June

Access date: 20 June

[12] Bateman, Sophie. 2020. „How does New Zealand’s healthcare system stack up against the rest of the world?" Newshub June 18th 2020. https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/world/2019/06/how-does-new-zealand-s-healthcare-system-stack-up-against-the-rest-of-the-world.html

Access date: 22 June

Access date: 22 June

[13] Young, Audrey. 2020. „Covid 19 coronavirus: NZj ill-prepared, caught with ‚pants down‘, says Professor Des Gorman; Jacinda Ardern rejects criticism“ New Zealand Herald April 30 2020. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12328348

Access date: 22 June

Access date: 22 June

[14] „Welcome to the 2019 Global Health Security Index“ Global Health Security Index https://www.ghsindex.org

Access date: 20 June

Access date: 20 June

[15] „2019 GHS Index Country Profile for New Zealand“ Global Health Security Index https://www.ghsindex.org/country/new-zealand/

Access date: 20 June

Access date: 20 June

[16]

„New Zealand Influenza Pandemic Plan: a framework for action“ Ministry of Health August 4 2017. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-influenza-pandemic-plan-framework-action

Access date: 20 June

„New Zealand Influenza Pandemic Plan: a framework for action“ Ministry of Health August 4 2017. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-influenza-pandemic-plan-framework-action

Access date: 20 June

[17]

Wilson, Nick. 2020. „NZ Should Prepare for a Potentially Severe Global Coronavirus Pandemic“ University of Otago February 6 2020.https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/2020/02/06/nz-should-prepare-for-a-potentially-severe-global-coronavirus-pandemic/

Access date: 30 June

Wilson, Nick. 2020. „NZ Should Prepare for a Potentially Severe Global Coronavirus Pandemic“ University of Otago February 6 2020.https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/2020/02/06/nz-should-prepare-for-a-potentially-severe-global-coronavirus-pandemic/

Access date: 30 June

[18] Boin, Arjen, Eric Stern, and Bengt Sundelius. 2017. The politics of crisis management: public leadership under pressure. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

[19] „Statistics and Research: Coronavirus (COVID-19) Cases“ Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases

Access date: 22 June

Access date: 22 June

[20]

„Covid-19 pandemic timeline: How the coronavirus started, spread and stalled life in New Zealand“ Radio New Zealand https://shorthand.radionz.co.nz/coronavirus-timeline/

Access date: 13 July

„Covid-19 pandemic timeline: How the coronavirus started, spread and stalled life in New Zealand“ Radio New Zealand https://shorthand.radionz.co.nz/coronavirus-timeline/

Access date: 13 July

[21]

„COVID-19 – current cases“ Ministry of Health June 22 2020. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-current-cases

Access date: 22 June

„COVID-19 – current cases“ Ministry of Health June 22 2020. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-current-cases

Access date: 22 June

[22]

[1] Statistics and Research: Coronavirus (COVID-19) Deaths“ Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases

Access date: 27 June

[1] Statistics and Research: Coronavirus (COVID-19) Deaths“ Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases

Access date: 27 June

[23]

„Statistics and Research: Mortality Risk of COVID-19“ Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/mortality-risk-covid?country=~NZL

Access date: 14 July

„Statistics and Research: Mortality Risk of COVID-19“ Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/mortality-risk-covid?country=~NZL

Access date: 14 July

[24]

„Statistics and Research: Mortality Risk of COVID-19“ Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/mortality-risk-covid?country=~NZL

Access date: 14 July

„Statistics and Research: Mortality Risk of COVID-19“ Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/mortality-risk-covid?country=~NZL

Access date: 14 July

[25]

COVID-19 – current cases“ Ministry of Health June 28 2020. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-current-cases

Access date: 28 June

COVID-19 – current cases“ Ministry of Health June 28 2020. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-current-cases

Access date: 28 June

[26]

„District health boards“ Ministry of Health February 12 2020 https://www.health.govt.nz/new-zealand-health-system/key-health-sector-organisations-and-people/district-health-boards

Access date: 28 June

„District health boards“ Ministry of Health February 12 2020 https://www.health.govt.nz/new-zealand-health-system/key-health-sector-organisations-and-people/district-health-boards

Access date: 28 June

[27] „COVID-19 – Testing rates for ethnicity and DHB“ Ministry of Health June 23 2020 https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-current-cases/covid-19-testing-rates-ethnicity-and-dhb Access date: 28 June

[28]

„Statistics and Research: Coronavirus (COVID-19) Testing“ Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-testing

Access date: 14 July

„Statistics and Research: Coronavirus (COVID-19) Testing“ Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-testing

Access date: 14 July

[29]

Boin, Arjen, Eric Stern, and Bengt Sundelius. 2017. The politics of crisis management: public leadership under pressure. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Boin, Arjen, Eric Stern, and Bengt Sundelius. 2017. The politics of crisis management: public leadership under pressure. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

[30]

„Central Government“ New Zealand Now June 22 2020. https://www.newzealandnow.govt.nz/living-in-nz/history-government/central-government

Access date: 30 June

„Central Government“ New Zealand Now June 22 2020. https://www.newzealandnow.govt.nz/living-in-nz/history-government/central-government

Access date: 30 June

[31]

Covid-19: State of National Emergency explained“ RNZ March 25 2020. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/412583/covid-19-state-of-national-emergency-explained

Access date: 30 June

Covid-19: State of National Emergency explained“ RNZ March 25 2020. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/412583/covid-19-state-of-national-emergency-explained

Access date: 30 June

[32]

„Coronavirus alert system: What you need to know“ stuff March 21 2020. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/120468173/coronavirus-alert-system-what-you-need-to-know

Access date: 30 June

„Coronavirus alert system: What you need to know“ stuff March 21 2020. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/120468173/coronavirus-alert-system-what-you-need-to-know

Access date: 30 June

[33]

Klein, Alice. 2020. „Why New Zealand decided to go for full elimination of the coronavirus“ NewScientist June 23 2020. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2246858-why-new-zealand-decided-to-go-for-full-elimination-of-the-coronavirus/

Access date: 29 June

Klein, Alice. 2020. „Why New Zealand decided to go for full elimination of the coronavirus“ NewScientist June 23 2020. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2246858-why-new-zealand-decided-to-go-for-full-elimination-of-the-coronavirus/

Access date: 29 June

[34]

Young, Audrey. 2020. „Covid 19 coronavirus: NZj ill-prepared, caught with ‚pants down‘, says Professor Des Gorman; Jacinda Ardern rejects criticism“ New Zealand Herald April 30 2020. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12328348

Access date: 22 June

Young, Audrey. 2020. „Covid 19 coronavirus: NZj ill-prepared, caught with ‚pants down‘, says Professor Des Gorman; Jacinda Ardern rejects criticism“ New Zealand Herald April 30 2020. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12328348

Access date: 22 June

[35]

Wilson, Nick. 2020. „NZ Should Prepare for a Potentially Severe Global Coronavirus Pandemic“ University of Otago February 6 2020.https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/2020/02/06/nz-should-prepare-for-a-potentially-severe-global-coronavirus-pandemic/

Access date: 30 June

Wilson, Nick. 2020. „NZ Should Prepare for a Potentially Severe Global Coronavirus Pandemic“ University of Otago February 6 2020.https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/2020/02/06/nz-should-prepare-for-a-potentially-severe-global-coronavirus-pandemic/

Access date: 30 June

[36] „Alert system overview“ New Zealand Government June 23 2020 https://uniteforrecovery.govt.nz/covid-19/covid-19-alert-system/alert-system-overview/Access date: 29 June

[37]

Graham-McLay, Charlotte. 2020. „Ardern urges New Zealanders to ‚act like you have Covid-19‘ as lockdown looms“ The Guardian March 25 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/25/ardern-urges-new-zealanders-to-act-like-you-have-covid-19-as-lockdown-looms

Access date: 29 June

Graham-McLay, Charlotte. 2020. „Ardern urges New Zealanders to ‚act like you have Covid-19‘ as lockdown looms“ The Guardian March 25 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/25/ardern-urges-new-zealanders-to-act-like-you-have-covid-19-as-lockdown-looms

Access date: 29 June

[38]

Conforti, Kaeli. 2020. „Alert Level 3 Restrictions To Begin In New Zealand This Week“ Forbes April 25 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kaeliconforti/2020/04/25/alert-level-3-restrictions-to-begin-in-new-zealand-this-week/#3da41e5e16fd

Access date: 29 June

Conforti, Kaeli. 2020. „Alert Level 3 Restrictions To Begin In New Zealand This Week“ Forbes April 25 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kaeliconforti/2020/04/25/alert-level-3-restrictions-to-begin-in-new-zealand-this-week/#3da41e5e16fd

Access date: 29 June

[39]

Conforti, Kaeli. 2020. „Alert Level 2 Restrictions To Begin In New Zealand This Week“ Forbes May 13 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kaeliconforti/2020/05/13/alert-level-2-restrictions-to-begin-in-new-zealand-this-week/#4b9518f46497

Access date: 29 June

Conforti, Kaeli. 2020. „Alert Level 2 Restrictions To Begin In New Zealand This Week“ Forbes May 13 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kaeliconforti/2020/05/13/alert-level-2-restrictions-to-begin-in-new-zealand-this-week/#4b9518f46497

Access date: 29 June

[40]

Ardern, Jacinda. 2020. „New Zealand moves to Alert Level 1“ New Zealand Government June 8 2020. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/new-zealand-moves-alert-level-1

Access date: 29 June

Ardern, Jacinda. 2020. „New Zealand moves to Alert Level 1“ New Zealand Government June 8 2020. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/new-zealand-moves-alert-level-1

Access date: 29 June

[41]

„About the Treasury“ The Treasury March 20 2018. https://treasury.govt.nz/about-treasury

Access date: 15 July

„About the Treasury“ The Treasury March 20 2018. https://treasury.govt.nz/about-treasury

Access date: 15 July

[42] „COVID-19 economic response“ The Treasury July 24 2020. https://treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/nz-economy/covid-19-economic-response

Access date: 24 July 2020

Access date: 24 July 2020

[43]

„Covid-19 Economic Package at a Glance: He Waka Eke Noa: We Are All Working Together – April 2020“ The Treasury April 15 2020. https://treasury.govt.nz/publications/glance/covid-19-economic-package-glance-he-waka-eke-noa-we-are-all-working-together-april-2020

Access date: 15 July

„Covid-19 Economic Package at a Glance: He Waka Eke Noa: We Are All Working Together – April 2020“ The Treasury April 15 2020. https://treasury.govt.nz/publications/glance/covid-19-economic-package-glance-he-waka-eke-noa-we-are-all-working-together-april-2020

Access date: 15 July

[44]

„Covid-19 economic response measures“ The Treasury June 26 2020. https://treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/new-zealand-economy/covid-19-economic-response/measures

Access date: 15 July

„Covid-19 economic response measures“ The Treasury June 26 2020. https://treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/new-zealand-economy/covid-19-economic-response/measures

Access date: 15 July

[45]

„Covid-19 tracing app launched earlier than expected” RNZ May 19 2020. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/417045/covid-19-tracing-app-launched-earlier-than-expected

Access date: 15 July

„Covid-19 tracing app launched earlier than expected” RNZ May 19 2020. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/417045/covid-19-tracing-app-launched-earlier-than-expected

Access date: 15 July

[46]

„NZ COVID Tracer app” Ministry of Health July 13 2020. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-novel-coronavirus-resources-and-tools/nz-covid-tracer-app

Access date: 15 July

„NZ COVID Tracer app” Ministry of Health July 13 2020. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-novel-coronavirus-resources-and-tools/nz-covid-tracer-app

Access date: 15 July

[47]

Wade, Amelia. 2020. “When did you last use the contact tracing app? Usage falls off a cliff as experts warn the system isn’t working” New Zealand Herald July 7 2020. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12346155

Access date: 15 July

Wade, Amelia. 2020. “When did you last use the contact tracing app? Usage falls off a cliff as experts warn the system isn’t working” New Zealand Herald July 7 2020. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12346155

Access date: 15 July

[48] Boin, Arjen, Eric Stern, and Bengt Sundelius. 2017. The politics of crisis management: public leadership under pressure. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

[49]

Matthews, Alex. 2020. „5 things New Zealand got right.“ Dw June 8 2020. https://www.dw.com/en/jacinda-ardern-leadership-in-coronavirus-response/a-53733397

Access date: 13 July

Matthews, Alex. 2020. „5 things New Zealand got right.“ Dw June 8 2020. https://www.dw.com/en/jacinda-ardern-leadership-in-coronavirus-response/a-53733397

Access date: 13 July

[50]

Mayfield, Jaqueline, Milton Mayfield. 2002. „Leader communication strategies: Critical paths to improving employee commitment“. American Business Review 20(2): 89-94.

Mayfield, Jaqueline, Milton Mayfield. 2002. „Leader communication strategies: Critical paths to improving employee commitment“. American Business Review 20(2): 89-94.

[51]

PM: stay at home and save lives“ Otago Daily Times March 25 2020. https://www.odt.co.nz/star-news/star-national/pm-stay-home-and-save-lives

Access date: 12 July

PM: stay at home and save lives“ Otago Daily Times March 25 2020. https://www.odt.co.nz/star-news/star-national/pm-stay-home-and-save-lives

Access date: 12 July

[52]

Menon, Praveen. 2020. „Ardern’s online messages keep spirits up in New Zealand’s coronavirus lockdown“. Reuters March 30 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-newzealand/arderns-online-messages-keep-spirits-up-in-new-zealands-coronavirus-lockdown-idUSKBN21H0HN

Access date: 13 July

Menon, Praveen. 2020. „Ardern’s online messages keep spirits up in New Zealand’s coronavirus lockdown“. Reuters March 30 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-newzealand/arderns-online-messages-keep-spirits-up-in-new-zealands-coronavirus-lockdown-idUSKBN21H0HN

Access date: 13 July

[53]

Roy, Eleanor Ainge. 2020. „Jacinda Ardern holds special coronavirus press conference for children“. The Guardian March 19 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/19/jacinda-ardern-holds-special-coronavirus-press-conference-for-children

Access date: 13 July

Roy, Eleanor Ainge. 2020. „Jacinda Ardern holds special coronavirus press conference for children“. The Guardian March 19 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/19/jacinda-ardern-holds-special-coronavirus-press-conference-for-children

Access date: 13 July

[54]

„ ‚The last thing I want is grief on grief‘ – Ardern issues plea for people not to attend tangis“ 1 news March 30 2020. https://www.tvnz.co.nz/one-news/new-zealand/last-thing-want-grief-ardern-issues-plea-people-not-attend-tangis

Access date: 13 July

„ ‚The last thing I want is grief on grief‘ – Ardern issues plea for people not to attend tangis“ 1 news March 30 2020. https://www.tvnz.co.nz/one-news/new-zealand/last-thing-want-grief-ardern-issues-plea-people-not-attend-tangis

Access date: 13 July

[55]

Anderson, Charles. 2020. „Ardern: New Zealand has ‚won battle‘ against community transmission of Covid-19“. The Guardian April 27 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/27/new-zealand-prepares-to-lift-strict-lockdown-after-eliminating-coronavirus

Access date: 13 July

Anderson, Charles. 2020. „Ardern: New Zealand has ‚won battle‘ against community transmission of Covid-19“. The Guardian April 27 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/27/new-zealand-prepares-to-lift-strict-lockdown-after-eliminating-coronavirus

Access date: 13 July

[56]

„Two new cases leaving isolation ‚an unacceptable failure of the system‘ – Ardern“ RNZ June 17 2020. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/419210/two-new-cases-leaving-isolation-an-unacceptable-failure-of-the-system-ardern

Access date: 13 July

„Two new cases leaving isolation ‚an unacceptable failure of the system‘ – Ardern“ RNZ June 17 2020. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/419210/two-new-cases-leaving-isolation-an-unacceptable-failure-of-the-system-ardern

Access date: 13 July

[57] Boin, Arjen, Eric Stern, and Bengt Sundelius. 2017. The politics of crisis management: public leadership under pressure. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

[58]

Fifield, Anna. 2020. „New Zealand isn’t just flattening the curve. It’s squashing it.“ The Washington Post April 7, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/new-zealand-isnt-just-flattening-the-curve-its-squashing-it/2020/04/07/6cab3a4a-7822-11ea-a311-adb1344719a9_story.html

Access date: 13 July

Fifield, Anna. 2020. „New Zealand isn’t just flattening the curve. It’s squashing it.“ The Washington Post April 7, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/new-zealand-isnt-just-flattening-the-curve-its-squashing-it/2020/04/07/6cab3a4a-7822-11ea-a311-adb1344719a9_story.html

Access date: 13 July

[59]

Ben Lazreg, Houssem, Adel Dhahri. 2020. „The COVID-19 „success story“: Why has the world singled out New Zealand for praise?“ ABC June 24 2020. https://www.abc.net.au/religion/why-single-out-new-zealands-coronavirus-response/12387528

Access date: 13 July

Ben Lazreg, Houssem, Adel Dhahri. 2020. „The COVID-19 „success story“: Why has the world singled out New Zealand for praise?“ ABC June 24 2020. https://www.abc.net.au/religion/why-single-out-new-zealands-coronavirus-response/12387528

Access date: 13 July

[60]

Ainge Roy, Eleanor. 2020. „Jacinda Ardern hits poll high as National urged to get over Bridges“ The Guardian May 18 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/19/jacinda-ardern-poll-high-popularity-national-simon-bridges-new-zealand-covid-19

Access date: 29 June

Ainge Roy, Eleanor. 2020. „Jacinda Ardern hits poll high as National urged to get over Bridges“ The Guardian May 18 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/19/jacinda-ardern-poll-high-popularity-national-simon-bridges-new-zealand-covid-19

Access date: 29 June

[61]

Anderson, Charles. 2020. „Jacinda Ardern and her government soar in populartiy during coronavirus crisis“ The Guardian May 1 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/01/jacinda-ardern-and-her-government-soar-in-popularity-during-coronavirus-crisis

Access date: 29 June

Anderson, Charles. 2020. „Jacinda Ardern and her government soar in populartiy during coronavirus crisis“ The Guardian May 1 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/01/jacinda-ardern-and-her-government-soar-in-popularity-during-coronavirus-crisis

Access date: 29 June

[62]

Walls, Jason. 2020. „A leaked poll shows National has dropped below 30 per cent, and Labour at 55 per cent“ New Zealand Herald May 1 2020. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12328854

Access date 6 July

Walls, Jason. 2020. „A leaked poll shows National has dropped below 30 per cent, and Labour at 55 per cent“ New Zealand Herald May 1 2020. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12328854

Access date 6 July

[63]

Medaris Miller, Anna. 2020. „New Zealand has no new coronavirus cases and just discharged ist last hospital patient. Here are the secrets to the country’s success.“ Business Insider May 28 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-new-zealand-beat-coronavirus-testing-tracing-trust-in-government-2020-5?r=DE&IR=T

Access date: 6 July

Medaris Miller, Anna. 2020. „New Zealand has no new coronavirus cases and just discharged ist last hospital patient. Here are the secrets to the country’s success.“ Business Insider May 28 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-new-zealand-beat-coronavirus-testing-tracing-trust-in-government-2020-5?r=DE&IR=T

Access date: 6 July

[64]

Boyd, Matt, Michael Baker, Nick Wilson. 2020. „Changes in mobility in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: NZ vs other countries and the stories it suggests“. University of Otago April 12 2020. https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/2020/04/12/changes-in-mobility-in-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-nz-vs-other-countries-and-the-stories-it-suggests/

Access date: 6 July

Boyd, Matt, Michael Baker, Nick Wilson. 2020. „Changes in mobility in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: NZ vs other countries and the stories it suggests“. University of Otago April 12 2020. https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/2020/04/12/changes-in-mobility-in-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-nz-vs-other-countries-and-the-stories-it-suggests/

Access date: 6 July

[65]

Ladley, Andrew. 2020. „New Zealand and COVID-19: Parliamentary accountability in time of emergencies”. Constitutionnet April 7 2020. http://constitutionnet.org/news/new-zealand-and-covid-19-parliamentary-accountability-time-emergencies

Access date: July 15

Ladley, Andrew. 2020. „New Zealand and COVID-19: Parliamentary accountability in time of emergencies”. Constitutionnet April 7 2020. http://constitutionnet.org/news/new-zealand-and-covid-19-parliamentary-accountability-time-emergencies

Access date: July 15

[66]

Parker, David. 2020. “New Zealand’s Covid-19 response- legal underpinnings and legal privilege” Beehive May 8 2020. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/new-zealand’s-covid-19-response-legal-underpinnings-and-legal-privilege

Access date: 15 July

Parker, David. 2020. “New Zealand’s Covid-19 response- legal underpinnings and legal privilege” Beehive May 8 2020. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/new-zealand’s-covid-19-response-legal-underpinnings-and-legal-privilege

Access date: 15 July

[67]

Sachdeva, Sam. 2020. “The committee keeping the government honest” Newsroom March 24 2020. https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2020/03/24/1099009/the-covid-committee-keeping-the-government-honest

Access date: July 15

Sachdeva, Sam. 2020. “The committee keeping the government honest” Newsroom March 24 2020. https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2020/03/24/1099009/the-covid-committee-keeping-the-government-honest

Access date: July 15

[68]

“Legislation and key documents” New Zealand Government. https://covid19.govt.nz/updates-and-resources/legislation-and-key-documents/

Access date: July 15

“Legislation and key documents” New Zealand Government. https://covid19.govt.nz/updates-and-resources/legislation-and-key-documents/

Access date: July 15

[69]

Ladley, Andrew. 2020. „New Zealand and COVID-19: Parliamentary accountability in time of emergencies”. Constitutionnet April 7 2020. http://constitutionnet.org/news/new-zealand-and-covid-19-parliamentary-accountability-time-emergencies

Access date: July 15

Ladley, Andrew. 2020. „New Zealand and COVID-19: Parliamentary accountability in time of emergencies”. Constitutionnet April 7 2020. http://constitutionnet.org/news/new-zealand-and-covid-19-parliamentary-accountability-time-emergencies

Access date: July 15

[70]

„WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 3 March 2020“ WHO March 3 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---3-march-2020#:~:text=COVID%2D19%20causes%20more,%25%20of%20those%20infected.

Access date: 13 July

„WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 3 March 2020“ WHO March 3 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---3-march-2020#:~:text=COVID%2D19%20causes%20more,%25%20of%20those%20infected.

Access date: 13 July