Chile

Seitenübersicht

[Ausblenden]1 Introduction

This student-curated Wiki deals with the crisis management of Chile during the actual COVID-19 pandemic, evaluating the aspects of Preparedness, Sense-making, Decision-making, Meaning-making and Legitimacy proposed by Boin et. al [1] .

1.1 General Information

Located in the southwest of Latin America, the „República de Chile“ has approximately 17,5 million inhabitants and is seperated into 15 different regions additional to the metropolitan region. The country´s regime is a presidential democracy, governed by the conservative head of government and head of state Sebastián Piñera Echenique since 2018 [2] .

He has been reelected in 2017, before he was already incumbent from 2010 until 2014. Being also an entrepreneur, Piñera is among the richest persons in the country and part of it´s elite with an asset of more than USD2,7 miliards[3] .

Due to the Human Development Report 2019, Chile is the leading southamerican country regarding the Human Development Index, the economic competitveness, the per capita income, the amount of globalisation, state of peace, economic freedom and perceived amount of corruption[4] .

He has been reelected in 2017, before he was already incumbent from 2010 until 2014. Being also an entrepreneur, Piñera is among the richest persons in the country and part of it´s elite with an asset of more than USD2,7 miliards[3] .

Due to the Human Development Report 2019, Chile is the leading southamerican country regarding the Human Development Index, the economic competitveness, the per capita income, the amount of globalisation, state of peace, economic freedom and perceived amount of corruption[4] .

1.2 Political Situation before the crisis

On one hand, Chile is among the richest countries on the whole continent, as a result of the neoliberal economic system that was implemented under dictator Augusto Pinochet with the help of the economist Milton Friedmann during the 1980s. The privatization of hospitals, highways, copper mines and even schools led to impressive economic growth, while the role of the state has been shrinked down to the minimum.On the other hand, the exact same system caused and still causes massive cleavages in todays society, where only the countrie´s elite is wealthy , while 14 percent of the population lives below the breadline. The vast majority of chileans has to live with a minium wage of approximately 330 Euro per month, facing similar costs of living as Germany[5] .

This major injustice led to massive nationwide anti-government protests since the beginning of october. A price increase of the metro tickets was the straw that broke the camel´s back and led to months of protests for a systemic change, shaped by the demand for the reformation of the health, pension and school system[6] , claiming overall social justice.

This major injustice led to massive nationwide anti-government protests since the beginning of october. A price increase of the metro tickets was the straw that broke the camel´s back and led to months of protests for a systemic change, shaped by the demand for the reformation of the health, pension and school system[6] , claiming overall social justice.

2 Preparedness

2.1 General measures

A political measure that enables the government to react to different types of crises, such as social crises or natural disasters, is the declaration of state of catastrophe. The decision to implement a national emergency state occurred on March 18, when president Piñera announced a 90-day state of catastrophe for the time being[7] .

Recently, the Chilean government declared the extension of the state of catastrophe, as the COVID19 cases in the country accumulate[8] .

By law, the military gets put in charge for keeping up the public order, implementing security and controlling the movement of essentials during a state of catastrophe. Furthermore, military officials are in the position to instruct public employees and local governments, and when considered necessary, also able to implement policies to maintain stability[9] .

Recently, the Chilean government declared the extension of the state of catastrophe, as the COVID19 cases in the country accumulate[8] .

By law, the military gets put in charge for keeping up the public order, implementing security and controlling the movement of essentials during a state of catastrophe. Furthermore, military officials are in the position to instruct public employees and local governments, and when considered necessary, also able to implement policies to maintain stability[9] .

2.2 Overall number of hospital beds and ventilators

According to the Chilean government, 3300 mechanical ventilators are available in the health sector. Additional to the normal number of 1229 beds with ventilators, 793 additional ventilators were bought by the government and approximately. The rest are anesthesia machines and pediatric ventilators that can be converted into mechanical ventilators that serve for a treatment of COVID-19.

In total, there are 27.000 hospital beds, 11.000 of them in the private sector. 4000 extra beds have been made available by the government through the contruction of 5 start-up hospitals[10] .

In total, there are 27.000 hospital beds, 11.000 of them in the private sector. 4000 extra beds have been made available by the government through the contruction of 5 start-up hospitals[10] .

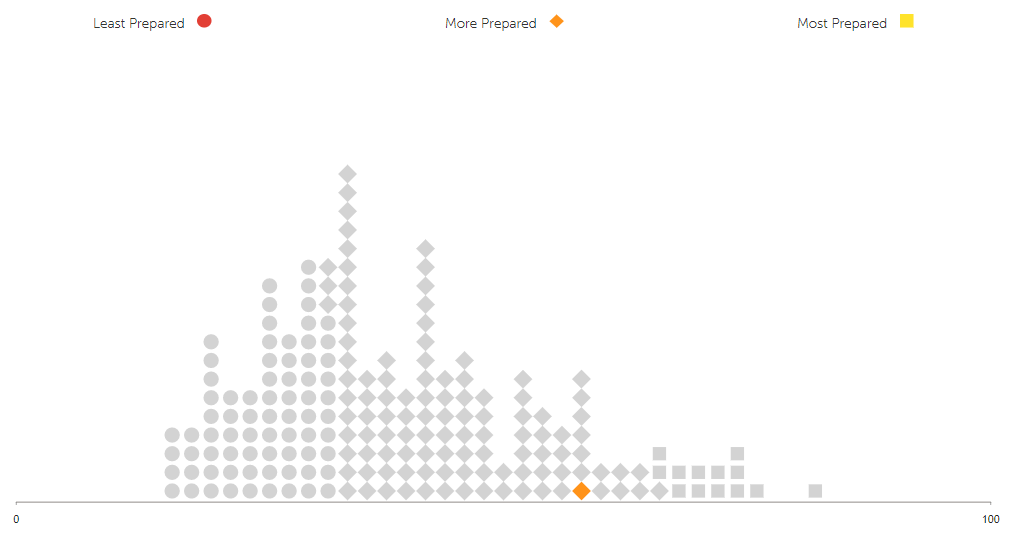

2.3 The GHS Index

The Global Health Security Index asseses the health security capabilities of 195 countries, following the aim to illustrate the preparedness but also gaps in the capacity of single countries in handling global health crises, in order to face upcoming crises in a more effective way[11] .

Chile overall is classified as a „More Prepared“ country and therefore located in the upper half of the spectre next to countries like Brazil, Austria, Argentina and Singapore.

Chile overall is classified as a „More Prepared“ country and therefore located in the upper half of the spectre next to countries like Brazil, Austria, Argentina and Singapore.

Overall performance of Chile as rated by the GHS Index (1)

In assesing the countries preparedness, it is useful to look at especially four out of the six categories, where I picked particular indicators from.

Categorie 1: Prevent

As a first important indicator,n Immunisation, measured through the vaccination rates, is common and widespread accross the country, although countries of the global north have a higher ranking with Chile being on place 76 out of 195.

Categorie 2: Detect

Regarding the Laboratory systems, there is sufficient evidence that the local Ministry of Health´s Department of Epidemiology is able to plan and coordinate the capacities for executing diagnostic tests for at least five of the six WHO-defined core tests.[12] Furthermore there is a website called ChileCompra Mercado Publico, where public agencies, such as the Ministry of Health, can request tenders for the production of laboratory equipment and similar matters [13] .

As another important indicator, Real time surveillance and reporting of infectious diseases is conducted by the Department of Epidemiology that also reported a potential case of public health emergency in 2017, due to an increase in hepatitis A cases [14] [15] .

In addition to that, there is an Epidemiological Surveillance System for the national and the sub-national level that allows the reporting of suspected and confirmed cases.

Categorie 3: Respond

Emergency preparedness and response planning adresses the existence of an emergency response plan. As a matter of fact, Chile has a public health emergency response plan that takes effect in the case of a potential pandemic. Published by Chile´s Ministry of Interior and Public Safety (ONEMI), the generalized plan focusses on responses to all kinds of emergencies and not only the outbreak of diseases with pandemic potential[16] . Not having an exclusive national plan for the extraordinary case of an emerging pandemic definitly counts as a weakness regarding Chile´s preparedness, although there is a special plan for pandemic influenza preparedness.

Emergency response operation tries to indicate whether there is an Emergency Operations Centre (EOC), in the case of Chile the ONEMI acts as the emergency operations centre. Despite this fact, the only simulations of emergency scenarios in the last years consisted of responses towards earthquakes and tsunamis[17] .

Linking public health and security authorities is made possible through standard operating procedures and guidelines defined by a plan that connects the specialized personnel of the Prefecture of Special Operations (GOPE) with the Ministry of Health given the case of an intentional biological threat. Although the spread of COVID19 isn´t a bioterrorism attack, Chile´s „Specific Plan for Emergencies of Variable Risk in Dangerous Materials“ can serve as a coordination tool during the actual crisis[18] .

Categorie 4: Health

Health capacity in clinics, hospitals and community care centres is measured through the available human resources, the existence of a health workforce strategy, the number of hospital beds and the capacity to isolate patients.

To make more meaning out of the numbers, I´ll draw a comparison between Chile (rank 149 out of 195) and the Netherlands (rank five) as they have a similar population size with about 18 million inhabitants.

While the Netherlands have 347.8 doctors and 1054.2 nurses and midwives per 100.000 people, Chile only has 103.3 doctors and 14.5 nurses [19] [20] .

Additional to that, there is no proof that the Chilean Ministry of Health has any strategy against the apparent workforce gaps in the health sector[21] [22] .

There hasn´t been found any evidence that the country has the capacity to isolate patients with highly communicable diseases [23] .

Categorie 1: Prevent

As a first important indicator,n Immunisation, measured through the vaccination rates, is common and widespread accross the country, although countries of the global north have a higher ranking with Chile being on place 76 out of 195.

Categorie 2: Detect

Regarding the Laboratory systems, there is sufficient evidence that the local Ministry of Health´s Department of Epidemiology is able to plan and coordinate the capacities for executing diagnostic tests for at least five of the six WHO-defined core tests.[12] Furthermore there is a website called ChileCompra Mercado Publico, where public agencies, such as the Ministry of Health, can request tenders for the production of laboratory equipment and similar matters [13] .

As another important indicator, Real time surveillance and reporting of infectious diseases is conducted by the Department of Epidemiology that also reported a potential case of public health emergency in 2017, due to an increase in hepatitis A cases [14] [15] .

In addition to that, there is an Epidemiological Surveillance System for the national and the sub-national level that allows the reporting of suspected and confirmed cases.

Categorie 3: Respond

Emergency preparedness and response planning adresses the existence of an emergency response plan. As a matter of fact, Chile has a public health emergency response plan that takes effect in the case of a potential pandemic. Published by Chile´s Ministry of Interior and Public Safety (ONEMI), the generalized plan focusses on responses to all kinds of emergencies and not only the outbreak of diseases with pandemic potential[16] . Not having an exclusive national plan for the extraordinary case of an emerging pandemic definitly counts as a weakness regarding Chile´s preparedness, although there is a special plan for pandemic influenza preparedness.

Emergency response operation tries to indicate whether there is an Emergency Operations Centre (EOC), in the case of Chile the ONEMI acts as the emergency operations centre. Despite this fact, the only simulations of emergency scenarios in the last years consisted of responses towards earthquakes and tsunamis[17] .

Linking public health and security authorities is made possible through standard operating procedures and guidelines defined by a plan that connects the specialized personnel of the Prefecture of Special Operations (GOPE) with the Ministry of Health given the case of an intentional biological threat. Although the spread of COVID19 isn´t a bioterrorism attack, Chile´s „Specific Plan for Emergencies of Variable Risk in Dangerous Materials“ can serve as a coordination tool during the actual crisis[18] .

Categorie 4: Health

Health capacity in clinics, hospitals and community care centres is measured through the available human resources, the existence of a health workforce strategy, the number of hospital beds and the capacity to isolate patients.

To make more meaning out of the numbers, I´ll draw a comparison between Chile (rank 149 out of 195) and the Netherlands (rank five) as they have a similar population size with about 18 million inhabitants.

While the Netherlands have 347.8 doctors and 1054.2 nurses and midwives per 100.000 people, Chile only has 103.3 doctors and 14.5 nurses [19] [20] .

Additional to that, there is no proof that the Chilean Ministry of Health has any strategy against the apparent workforce gaps in the health sector[21] [22] .

There hasn´t been found any evidence that the country has the capacity to isolate patients with highly communicable diseases [23] .

2.4 Evaluation of preparedness

As conclusion, Chile is neither among the best prepared nor among the worst prepared countries in facing the COVID-19 crisis. Although there is a high number of cases, the overall circumstances and the adopted measures before the crisis helped to prevent an even worse outbreak of the virus.

Chile is especially well prepared regarding controlling and coordination issues as the different ministries are linked to each other and catastrophe plans are at hand, probably a consequence of a government that was relatively stable until last october and a high amount of economic resources.

On the other hand, the capacities of the health system are extremly bad as there is a shortage of hospital beds and human resources. What sharpens this problem is the low quality of services that are covered by the public health insurance (FONASA) that 80% of the Chileans are part of. The rest of the population are members of a private health insurance (ISAPRES), that is orientated in profit maximation and charges high subscriptions.Having a system that is very exclusive towards members of lower social classes as they can´t afford an equivalent treatment in the case of sickness, there is a massive health-regarding cleavage in society[24] . Still, the health-care system is advanced compared to other latinamerican states.

It is important to mention that we have to enjoy the results of the GHS Index carefully, as for example the U.S. are rated as the best prepared country [25] and currently face the highest number of caseloads worldwide. Nevertheless the numbers and the data provided by the authors serves as a good basis for comparison.

Chile is especially well prepared regarding controlling and coordination issues as the different ministries are linked to each other and catastrophe plans are at hand, probably a consequence of a government that was relatively stable until last october and a high amount of economic resources.

On the other hand, the capacities of the health system are extremly bad as there is a shortage of hospital beds and human resources. What sharpens this problem is the low quality of services that are covered by the public health insurance (FONASA) that 80% of the Chileans are part of. The rest of the population are members of a private health insurance (ISAPRES), that is orientated in profit maximation and charges high subscriptions.Having a system that is very exclusive towards members of lower social classes as they can´t afford an equivalent treatment in the case of sickness, there is a massive health-regarding cleavage in society[24] . Still, the health-care system is advanced compared to other latinamerican states.

It is important to mention that we have to enjoy the results of the GHS Index carefully, as for example the U.S. are rated as the best prepared country [25] and currently face the highest number of caseloads worldwide. Nevertheless the numbers and the data provided by the authors serves as a good basis for comparison.

3 Sense-making

3.1 COVID-19 caseload

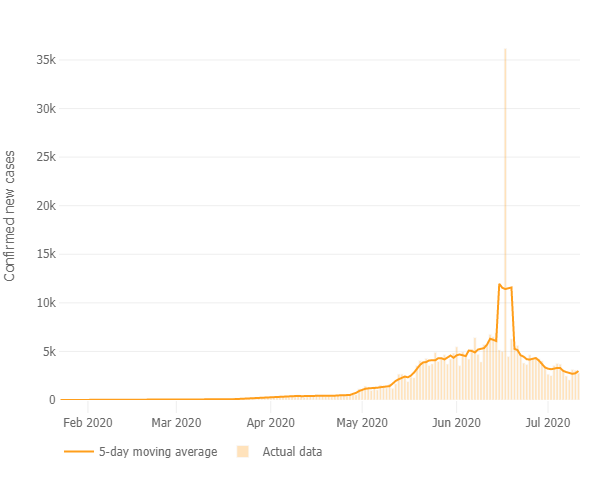

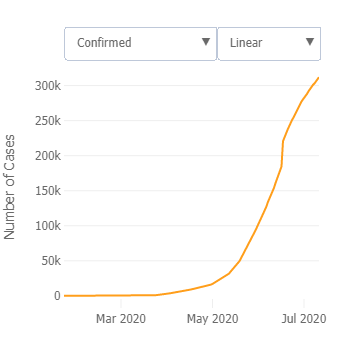

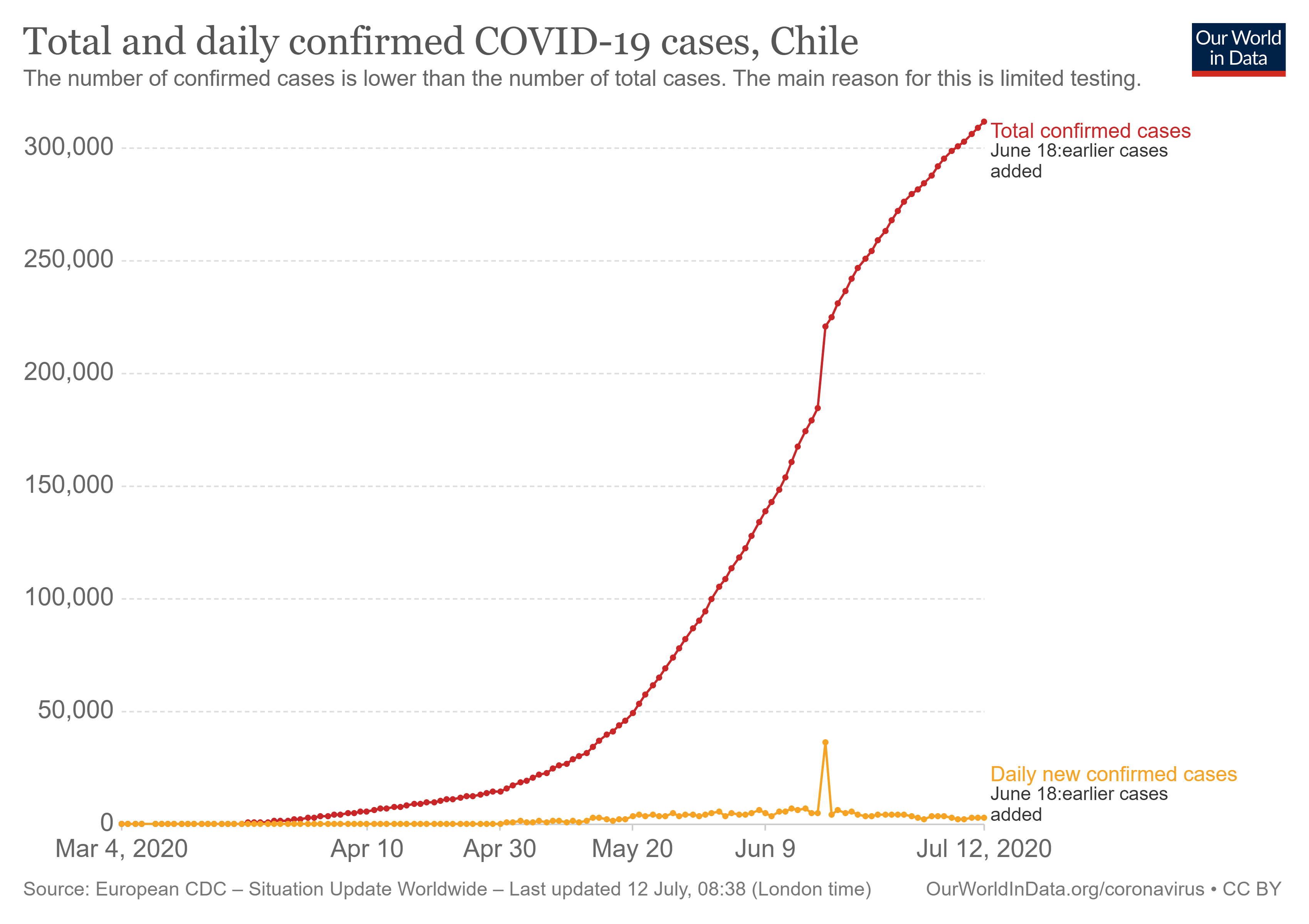

Number of confirmed new cases as of july 13 (2) |  Total number of cases as of july 13 (3) |

Although Chile is among the 10 most affected countries in the world next to India and Brazil, the number of confirmed new cases is currently decreasing[26] .

The first case of COVID-19 in Chile was reported on the third of march. Since then, the country has reported 312,029 cases, and 6,881deaths as of July 13 [27] .

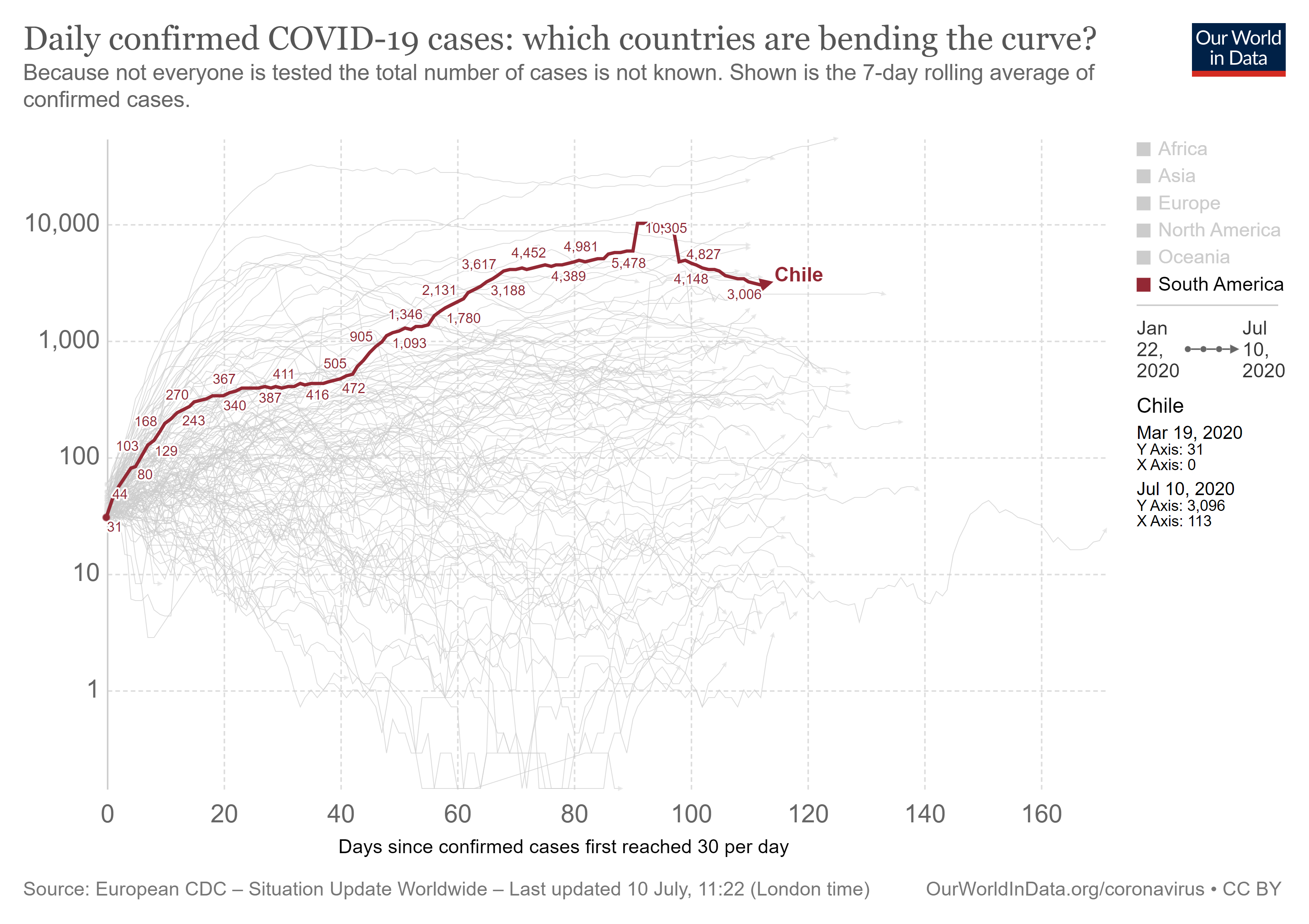

Total and daily confirmed cases (4)

The eye-catching peak in the number of daily confirmed COVID-19 cases is because on June 18, earlier cases have been added to the total number of confirmed cases what explains the massive number of new confirmed cases on that day. The number jumped from 5.013 to 36.179[28] .

Furthermore there has been a change in methodology of accounting and reporting deaths, where the number of probable deaths is added to the number of confirmed deaths[29] . As a result the death toll has nearly doubled with more than 7000 fatalities as of June 20 [30] .

Beneath that, the increasing numbers from march until june can explained in terms of the failed approach of imposing dynamic lockdowns for single municipalities, what is going to be discussed later on. After the first neighborhoods of Santiago have been quarantined, officials falsely believed that the outbreak was embanked. But due to the movement of workers across the capital, the virus was carried to poorer neighborhoods where it could spread easily as a lot of people live under precarious and overcrowded conditions [31]

By implementing a total lockdown for the whole city of Santiago, officials managed to contain a wider spreading of the virus.

Furthermore there has been a change in methodology of accounting and reporting deaths, where the number of probable deaths is added to the number of confirmed deaths[29] . As a result the death toll has nearly doubled with more than 7000 fatalities as of June 20 [30] .

Beneath that, the increasing numbers from march until june can explained in terms of the failed approach of imposing dynamic lockdowns for single municipalities, what is going to be discussed later on. After the first neighborhoods of Santiago have been quarantined, officials falsely believed that the outbreak was embanked. But due to the movement of workers across the capital, the virus was carried to poorer neighborhoods where it could spread easily as a lot of people live under precarious and overcrowded conditions [31]

By implementing a total lockdown for the whole city of Santiago, officials managed to contain a wider spreading of the virus.

Development of the curve (5)

3.2 Testing and reporting logic

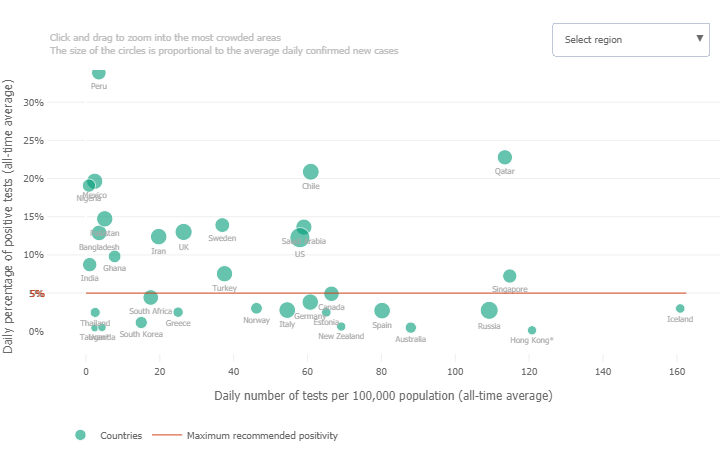

International comparison of positivity rates and tests per capita (6)

According to the John Hopkins University, „(…) testing programs should be scaled to the size of their epidemic, not the size of the population.“ (John Hopkins University, 28.06.20) so that governments can identify new cases and act effectively. It is possible for a country to controll the spread of the virus also with testing programs that have a low number of tests per capita.

An effective tool to assess whether a government is testing enough is the „positivity rate“, defined as the number of positive COVID-19 tests out of all tests conducted. A high rate implies that a government only tests the sickest patients without creating a neccessary overview of the population.

Before an abolishment of social distancing measures, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes that a government should recognize positivity rates below 5% for at least two weeks.

In the case of Chile, with a daily number of 61 tests per 1000 people, it becomes clear that the government didn´t cast a net that is wide enough to capture the whole situation yet, having an average daily positivity rate of 20,90%[32] .

In comparison, countries like Norway, New Zealand and Spain managed to fall below the threshold of 5%.

An effective tool to assess whether a government is testing enough is the „positivity rate“, defined as the number of positive COVID-19 tests out of all tests conducted. A high rate implies that a government only tests the sickest patients without creating a neccessary overview of the population.

Before an abolishment of social distancing measures, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes that a government should recognize positivity rates below 5% for at least two weeks.

In the case of Chile, with a daily number of 61 tests per 1000 people, it becomes clear that the government didn´t cast a net that is wide enough to capture the whole situation yet, having an average daily positivity rate of 20,90%[32] .

In comparison, countries like Norway, New Zealand and Spain managed to fall below the threshold of 5%.

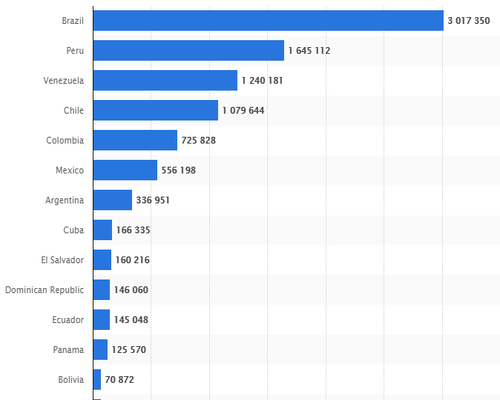

Number of COVID-19 tests performed in selected countries in Latin America as of June 29 (7)

According to the website of the chilean government, capacities are large enough to perform the Coronavirus diagnostic PCR test for free for all members of the public health insurance agency FONASA.

In the definition of cases, the goverment differentiates between three types. A suspicious case is a person with at least two symptons of COVID-19, without having had direct contact with a positive case and also anyone with a severe respiratory infection.

For a confirmed case, a quarantine for 14 days from the beginning of the symptoms is determined if the patient presents symptoms. If not, the quarantine will be imposed for 14 days from the diagnosis.

Probable cases sum up those who show symptoms but have an an indetermined testing result. They are treated as a verified case and added to the active cases, everyone affected must remain in quarantine for 14 days.

Additional to those categories, persons who had close contact to a person diagnosed with COVID-19 have to adhere to the isolation measures for 14 days [33] .

In the definition of cases, the goverment differentiates between three types. A suspicious case is a person with at least two symptons of COVID-19, without having had direct contact with a positive case and also anyone with a severe respiratory infection.

For a confirmed case, a quarantine for 14 days from the beginning of the symptoms is determined if the patient presents symptoms. If not, the quarantine will be imposed for 14 days from the diagnosis.

Probable cases sum up those who show symptoms but have an an indetermined testing result. They are treated as a verified case and added to the active cases, everyone affected must remain in quarantine for 14 days.

Additional to those categories, persons who had close contact to a person diagnosed with COVID-19 have to adhere to the isolation measures for 14 days [33] .

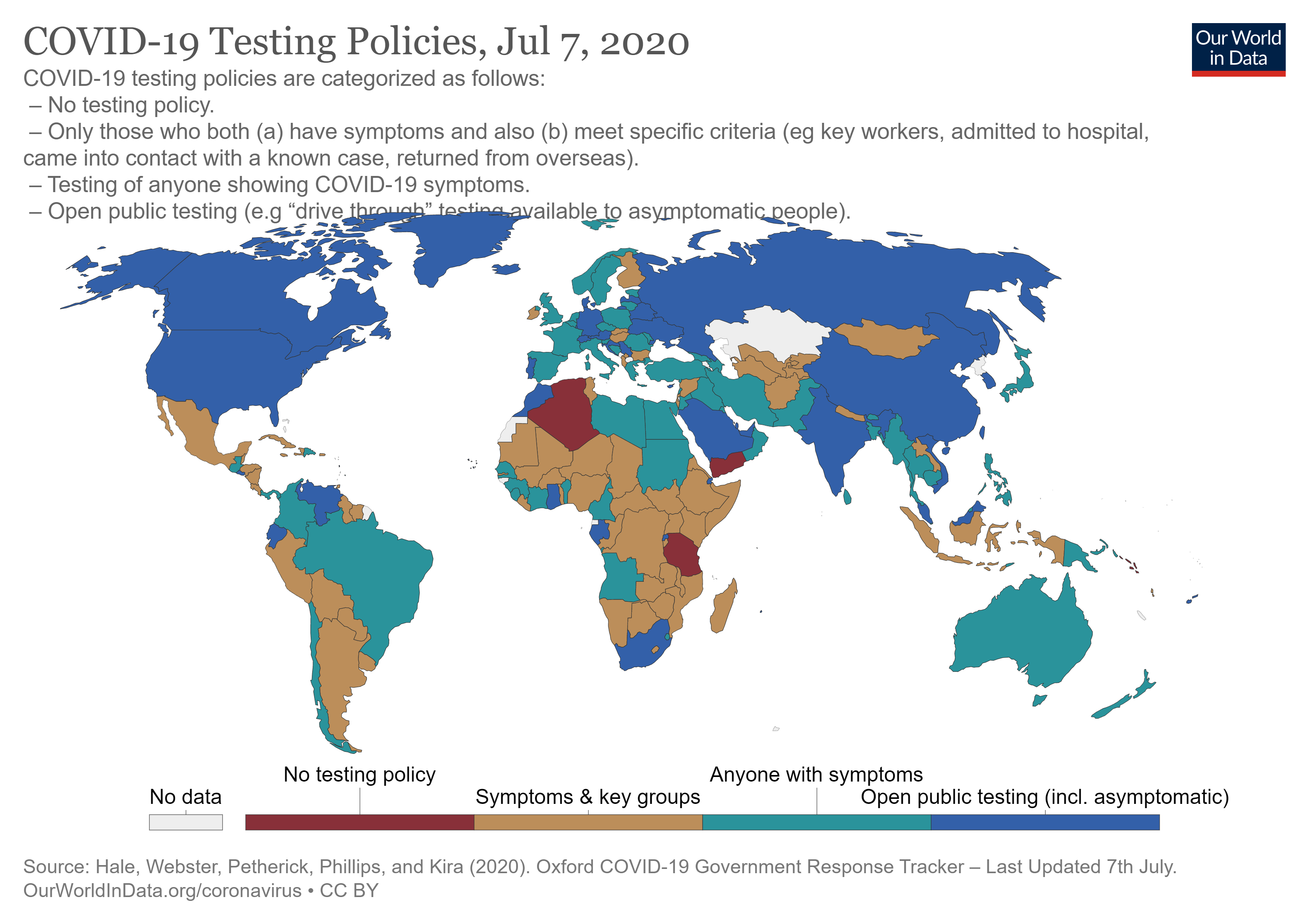

When comparing the overall testing policies, it becomes clear that Chile follows a rather strict approach than its neighboring countries, testing anyone showing COVID-19 syptoms similar to France and Spain.

Meanwhile countries like Argentina, Bolivia and Peru only test those persons who have symptoms AND meet specific criteria, like contact to an infected person or someone who has returned from overseas.

Meanwhile countries like Argentina, Bolivia and Peru only test those persons who have symptoms AND meet specific criteria, like contact to an infected person or someone who has returned from overseas.

Comparison of worldwide testing policies for COVID-19 (8)

4 Decision-Making and Coordinating

4.1 Implemented measures

Instead of a national lockdown, Chile follows the approach of flexible lockdowns of districts and municipalities, where health officials are able to cordon off the areas where outbreaks are detected [34] . Single municipalities all over the country have been put under quarantine at different points of time. Only a few of them have been quarantined since march, other municipalities followed during april, and a lot more followed in may and june. While some communes just imposed a quarantine recently, others limited the quarantine period to only a few weeks.

As a consequence of the increasing number of cases, the whole city of Santiago has been put under quarantine for an uncertain amount of time [35] . Additional to that, the movement of people has been restricted so that they can´t leave their home without reason and penalties for violating the quarantine or the curfew have been implemented (ibid.).

Furthermore, 123 posts of Sanitary Authority have been established to control travelers for their temperature so they don´t have to be quarantined immediately. Chilean citizen can obtain a Health Passport online that is verified at the Sanitary customs and allows, after the control for sickness, the entry to every region. You can find a map of the sanitary control points below.

During the national dusk-to-dawn curfew, no one will be able to move freely except for those who have a permission. Those are only delivered in the case of health emergency or death and can be requested at police stations or online [36]

As a consequence of the increasing number of cases, the whole city of Santiago has been put under quarantine for an uncertain amount of time [35] . Additional to that, the movement of people has been restricted so that they can´t leave their home without reason and penalties for violating the quarantine or the curfew have been implemented (ibid.).

Furthermore, 123 posts of Sanitary Authority have been established to control travelers for their temperature so they don´t have to be quarantined immediately. Chilean citizen can obtain a Health Passport online that is verified at the Sanitary customs and allows, after the control for sickness, the entry to every region. You can find a map of the sanitary control points below.

During the national dusk-to-dawn curfew, no one will be able to move freely except for those who have a permission. Those are only delivered in the case of health emergency or death and can be requested at police stations or online [36]

Sanitary customs in every region of the country.

Region number 22 marks the Metropolitan Region where Santiago is located (9)

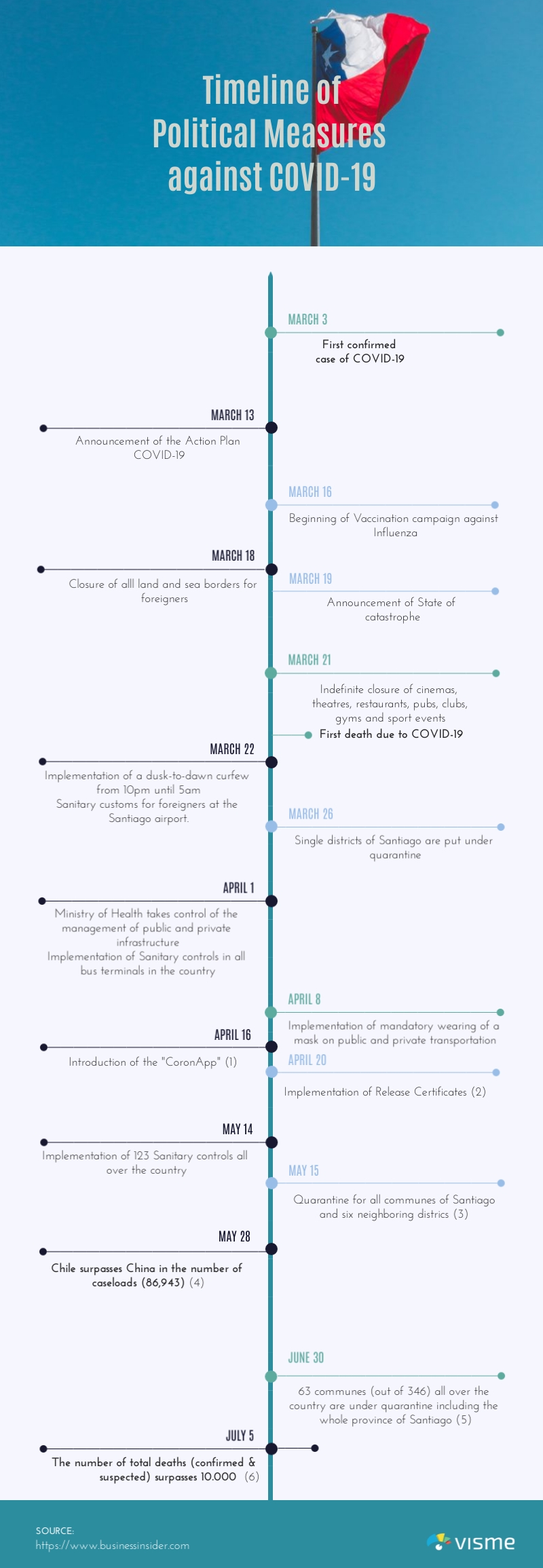

The Action Plan COVID-19 (Plan de Accion Coronavirus) is the first officially published plan by the chilean government.

In the corresponding document, abstract and concrete policy measures in six core areas are defined.

The most important addtional measure is the designation of the Ministry of Health as interministerial coordinator in the fight against COVID-19.

All of the following information has been taken out of the Action Plan COVID-19 [37] .

Education

Closure of schools and universitites. A mandatory quarantine of 14 days is implemented for everyone having a family member that is infected, who is infected themself or if there are two or more confirmed cases in one class. Preschool and school classes have been suspended between March 30 and April 12, and the winter break started early on April 13 until April 24.

Health

Employees have a right for sick-leave, if they had contact with an infected person.

For everyone that is in need of it and also member of the public health insurance FONASA, testing for a COVID-19 infection will be free.

Furthermore, the capacity of the health system is increased through a higher amount of available hospital beds and the support of the military.

Last but not least, a fund of 220 Milliards of Pesos (approximately 240 milliards of Euros) will be established according to the plan, accounting for the construction of hospitals and the medical care of the population.

Mass events

All public events with more than 50 people are prohibited for an uncertain period.

Border control

Additional to the closure of borders of foreign people, Chileans or foreigners residing in Chile must undergo a mandatory 14-day quarantine when entering the country. All chilean passenger cruise ports are closed from March 15 to September 30.

Provision with goods

Everything necessary will be done to maintain the normal provision of the population. The declaration of the state of catastrophe will support this goal.

Traffic

Public transport continues to be open in order to remain the personal liberty, although higher hygiene standards will be implemented by desinfecting the metro, busses and trains regularly.

On march 16, the government announced another document called "Plan para enfrentar el Coronavirus", where measures from the first plan are partly specified and additional statements are made, such the implementation of fines and prison sentences for everyone not following the instructions and the collaboration with the armed forces in order to protect the borders[38] . For giving a better overview, the timeline doesn´t differentiate between the two documents but shows the measures that apply for the very moment.

The Action Plan against COVID-19 is accompanied by the declaration of a constitutional state of exception (or state of catastrophe) announced by the government on March 19.

Regarding to the official website, this measure aims to anticipate and prepare for future stages of the pandemic. It allows for the restriction of meetings in public and mobility, the establishment of quarantines or curfews and the ensurement of the distribution of public goods and services [39] .

Other countries that declared a state of catastrophe are Bulgaria and Spain on March 13, Portugal on March 18 and New Zealand on March 25.

In order to conclude more expertise as well as to legitimize the decisions by the government, a COVID-19 Advisory Committee has been established, consisting of epidemiologists and health experts that work together with the ministry of health[40] .

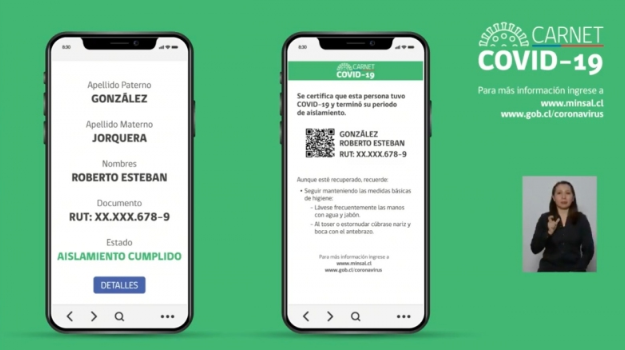

4.2 Immunity passport

As one of the first countries worldwide, the chilean government issued plans to implement an „Immunity Passport“, a physical or digital card that would free holders from quarantine and other restrictions. Everyone who recovered from a confirmed infection with COVID-19 could then return to work, as they can help the community without presenting a risk according to former Health minister Jaime Manalich. Any further details haven´t been specified by officials, who promised a plan for mass testing. As there is no evidence that long-term immunity against COVID-19 exists, the planned approach was highly criticized by scientists and the public. The announcement that patients who appeared to have recovered have been tested positive anew [41] couldn´t be proven true by the Corean Center for Disease Control [42] , but still, a confirmation of immunity isn´t guaranteed.

On April 24, the WHO expressed the concern that “there is not enough evidence about the effectiveness of antibody-mediated immunity to guarantee the accuracy of an ‘immunity passport’ or ‘risk-free certificate’” and that a certificate could encourage people to “ignore public health advice” [43]

Despite the WHO warning, the chilean government then came up with release certificates called COVID-19 Card („Carnet COVID-19/ Carnet sanitario“) as the first country worldwide.

This document expires after 3 months and the owner will again be considered to have the same probability of an infection as everyone else, but in the mean time it is meant to provide security and the possibility to help others without taking a risk (Fraser 2020).

Everyone who has recovered and is „non-infectious“ according to the following criteria can obtain the card:

On April 24, the WHO expressed the concern that “there is not enough evidence about the effectiveness of antibody-mediated immunity to guarantee the accuracy of an ‘immunity passport’ or ‘risk-free certificate’” and that a certificate could encourage people to “ignore public health advice” [43]

Despite the WHO warning, the chilean government then came up with release certificates called COVID-19 Card („Carnet COVID-19/ Carnet sanitario“) as the first country worldwide.

This document expires after 3 months and the owner will again be considered to have the same probability of an infection as everyone else, but in the mean time it is meant to provide security and the possibility to help others without taking a risk (Fraser 2020).

Everyone who has recovered and is „non-infectious“ according to the following criteria can obtain the card:

- Patients with symptoms and positive diagnosis, with 14 days without symptoms

- Patients who has been hospitalized and discharged receives the card from the 14th day after the first symptoms

- Discharged patients who still had symptoms need to wait one more week

- People with compromised immunity will receive a card 28 days after the onset of symptoms

Digital version of the release certificate (10)

4.3 The "CoronApp"

Implemented on April 16, there is an official App provided by the Chilean government, called CoronApp. Among other countries that developed Apps are India, Taiwan, South Korea, Norway and the Netherlands.

In Chile, the governmental website for Digitalisation informs about the features of the application, it serves most importantly for the monitoring of symptoms, the controlling of quarantine regulations and the reporting of risky situations, all in ordert o prevent further infections. Updated information by health authorities will also be delivered by this App.

Furthermore, the CoronApp helps potential infected people with a self-diagnosis system, in severe cases it recommends going to a healthcare center. In general, users are able to control how their infection is evolving, in the case of questions the App provides a virtual assisent based on artificial intelligence.

When allowing for tracking of the location, users receive notifications when they leave their quarantine area. They are also able to collaborate with the police and health authorities when reporting risky situations in public such as the gathering of crowds. This is made possible as a measure for taking quick actions in dangerous situations as explained by the website [45] .

The Chilean approach is comparable with the App provided by the Netherlands, as its mainly about the surveillance of symptoms and doesn´t serve for the tracking of individuals to avoid the spreading of the virus like for example in Taiwan or Israel.

In Chile, the governmental website for Digitalisation informs about the features of the application, it serves most importantly for the monitoring of symptoms, the controlling of quarantine regulations and the reporting of risky situations, all in ordert o prevent further infections. Updated information by health authorities will also be delivered by this App.

Furthermore, the CoronApp helps potential infected people with a self-diagnosis system, in severe cases it recommends going to a healthcare center. In general, users are able to control how their infection is evolving, in the case of questions the App provides a virtual assisent based on artificial intelligence.

When allowing for tracking of the location, users receive notifications when they leave their quarantine area. They are also able to collaborate with the police and health authorities when reporting risky situations in public such as the gathering of crowds. This is made possible as a measure for taking quick actions in dangerous situations as explained by the website [45] .

The Chilean approach is comparable with the App provided by the Netherlands, as its mainly about the surveillance of symptoms and doesn´t serve for the tracking of individuals to avoid the spreading of the virus like for example in Taiwan or Israel.

The "CoronApp" (11)

4.4 Coordination between different levels

The Action Plan COVID-19 also contains the information that measures in all areas can be modified or extended for certain territories like whole regions or communities if necessary.

This imposes the question whether a federalist structure is a chance or a difficulty in situations like this. For sure multi level governance can lead problems but it can lead to chances of effective and coordinated regional responses as well.

In order to answer the question, it is helpful to deal with a Paper published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, with the title: The territorial impact of COVID-19: Managing the crisis across levels of government.

This imposes the question whether a federalist structure is a chance or a difficulty in situations like this. For sure multi level governance can lead problems but it can lead to chances of effective and coordinated regional responses as well.

In order to answer the question, it is helpful to deal with a Paper published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, with the title: The territorial impact of COVID-19: Managing the crisis across levels of government.

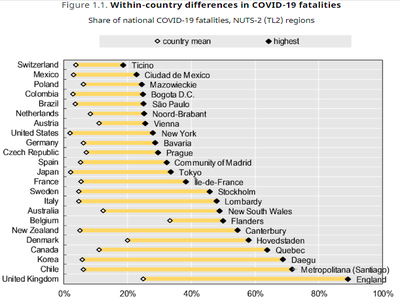

Cleavage between the country´s average rate of COVID-19 fatalities and the highest rate in the Metropolitan region in and around of the capital Santiago (12)

The most important conclusion is that the graphic emphasizes the necessity of coordination between national and sub-national levels as well as the importance of different measures in different regions, as Metropolitan Santiago accounts for 85% of the cases as of June 6 [46] .

One factor accounting for this huge disparity is the development of the first „clusters“ of cases, where large cities often face a higher risk due to internationalisation, tourism and similar reasons[47] .

Another factor is that contagion is faster to spread in urban areas (ibid.).

What is important to say is that density of population per se is not the problem, but rather density being connected with poverty, poor housing conditions and the worse access to health care[48] .

Chile´s way of dealing with regional differences and enable vertical coordination inlcudes the establishment of a Social Commitee for COVID-19 (Mesa social por COVID-19) at the national level and replicating the same commitee at the regional level[49] .

It consists of mayors, government authorities, academics and experts from the health sector that meet twice a week in order to strengten the Action Plan COVID-19[50] .

As the OECD claims, it is recommendable to implement „(…) multi-level coordination bodies in order to minimise the risk of a fragmented crisis response.“ (OECD, 29.06.20) and use them to implement strategies, make decisions and develop solutions [51] .

Furthermore, the central chilean government transferred USD 100 Million to municipalities as a compensation for lacking municipal revenues. Those funds will be distributed proportional to the population and vulnerability rates of the municipalities, mayors will be in the position to decide on the use and the distribution of these funds [52] .

Another way to make use of federal structures during a crisis is to introduce more flexibility in administrative procedures at the subnational level, so agencies can react faster and in a simpler way (ibid.).

In Chile, the subsecretary for regional development and administration (SUBDERE) worked together with different municipal associations for coordinating measures to simplify administrative procedures for citizens what leads to more flexibility during the time of a crisis (ibid.).

One factor accounting for this huge disparity is the development of the first „clusters“ of cases, where large cities often face a higher risk due to internationalisation, tourism and similar reasons[47] .

Another factor is that contagion is faster to spread in urban areas (ibid.).

What is important to say is that density of population per se is not the problem, but rather density being connected with poverty, poor housing conditions and the worse access to health care[48] .

Chile´s way of dealing with regional differences and enable vertical coordination inlcudes the establishment of a Social Commitee for COVID-19 (Mesa social por COVID-19) at the national level and replicating the same commitee at the regional level[49] .

It consists of mayors, government authorities, academics and experts from the health sector that meet twice a week in order to strengten the Action Plan COVID-19[50] .

As the OECD claims, it is recommendable to implement „(…) multi-level coordination bodies in order to minimise the risk of a fragmented crisis response.“ (OECD, 29.06.20) and use them to implement strategies, make decisions and develop solutions [51] .

Furthermore, the central chilean government transferred USD 100 Million to municipalities as a compensation for lacking municipal revenues. Those funds will be distributed proportional to the population and vulnerability rates of the municipalities, mayors will be in the position to decide on the use and the distribution of these funds [52] .

Another way to make use of federal structures during a crisis is to introduce more flexibility in administrative procedures at the subnational level, so agencies can react faster and in a simpler way (ibid.).

In Chile, the subsecretary for regional development and administration (SUBDERE) worked together with different municipal associations for coordinating measures to simplify administrative procedures for citizens what leads to more flexibility during the time of a crisis (ibid.).

5 Meaning making

5.1 Definiton

Boin et al. define meaning making „(…) as the attempt to reduce public and political uncertainty and inspire confidence in crisis leaders by formulating and imposing a convincing narrative.“ (p.79).

5.2 Crisis narrative and Framing

In order to evaluate the meaning making process, it is important to investigate the crisis narrative that has been communicated.

In the first Action Plan COVID-19, president Piñera emphasizes the early action of the government and claims that since January, work groups have been formed, plans have been made, equipment has been bought and laboratories have been prepared. Furthermore he points out that the government iniciated a health-orientated border protection, a strengthening of hospital capacity through a consolidation of health care workers and the opening of five new hospitals in different regions [53] .

This gives the impression that the crisis has been anticipated by those in force and furthermore has been taken seriously from the beginning.

In an article, published by the governmental website CHILE reports in the beginning of May, this image is intensified. The successful implementation of policy measures such as the national curfew and the strengthening of the health system since January are emphasized. The article contains quotes such as „The next few weeks will be the hardest and require the very best from all of us.“ and „Everyone in our healthcare system is working tirelessly and giving everything they can to meet the challenge of providing the healthcare that our fellow Chileans – all of our fellow Chileans – need.“ by president Sebastian Piñera [54] .

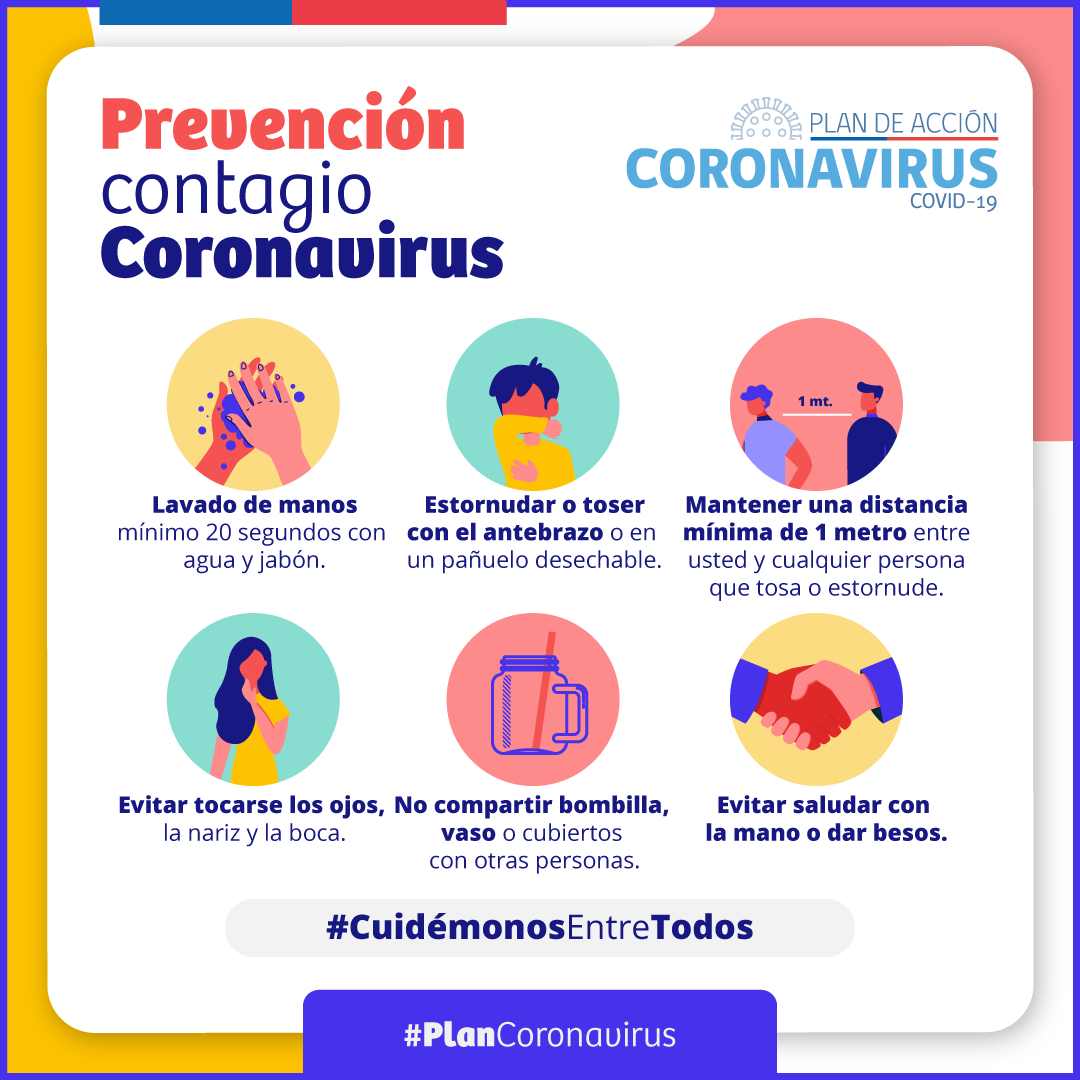

As for now, the government actknowledges the crisis in a serious way as depicted on several websites that call on the population to take care.

In the first Action Plan COVID-19, president Piñera emphasizes the early action of the government and claims that since January, work groups have been formed, plans have been made, equipment has been bought and laboratories have been prepared. Furthermore he points out that the government iniciated a health-orientated border protection, a strengthening of hospital capacity through a consolidation of health care workers and the opening of five new hospitals in different regions [53] .

This gives the impression that the crisis has been anticipated by those in force and furthermore has been taken seriously from the beginning.

In an article, published by the governmental website CHILE reports in the beginning of May, this image is intensified. The successful implementation of policy measures such as the national curfew and the strengthening of the health system since January are emphasized. The article contains quotes such as „The next few weeks will be the hardest and require the very best from all of us.“ and „Everyone in our healthcare system is working tirelessly and giving everything they can to meet the challenge of providing the healthcare that our fellow Chileans – all of our fellow Chileans – need.“ by president Sebastian Piñera [54] .

As for now, the government actknowledges the crisis in a serious way as depicted on several websites that call on the population to take care.

Measures of prevention recommended by the Chilean government (13)

But nevertheless, mixed messages about the severity of the COVID-19 crisis have been communicated in the past what led to a delayed or wrong transportation of an appropriate crisis narrative .In the middle of march, after a few cases already had been confirmed, president Sebastian Piñera claimed that Chile is in a state of preparation way better than Italy By successfully implementing flexible lockdowns for districs that were affected by a breakout of COVID-19, the situation seemed under control and by the end of april, single offices and even malls reopened [55] . After the massive increase of the number of caseloads at the end of may, this turned out to be a huge mistake, an example for an inappropriate framing of the severe situation.

At the same time, former health minister Jaime Mañalich stated that he never knew about the precarious living conditions and the amount of poverty in the poorer districts of Santiago[56] , demonstrating ignorance and lack of knowledge.

It was also during april when president Piñera asked workers in the public sector to return to work despite critiques from the scientific community. Shortly after, government authorities began talking about a „new normality“ which led to the opening of single offices and malls as mentioned before. Those measures were adapted based on the idea of Piñera´s government that the country already had overcome the worst part of the crisis, which was clearly not the case [57] .

At the same time, former health minister Jaime Mañalich stated that he never knew about the precarious living conditions and the amount of poverty in the poorer districts of Santiago[56] , demonstrating ignorance and lack of knowledge.

It was also during april when president Piñera asked workers in the public sector to return to work despite critiques from the scientific community. Shortly after, government authorities began talking about a „new normality“ which led to the opening of single offices and malls as mentioned before. Those measures were adapted based on the idea of Piñera´s government that the country already had overcome the worst part of the crisis, which was clearly not the case [57] .

5.3 Evaluation of crisis framing

Following Boin et al. (2017) an effective frame consists of five aspects: an explanation of what has happened, the offering of guidance, the creation of hope, showing of empathy and the suggestion that leaders are in control [58] .

In the Chilean case, an explanation of what has happened is definitly missing, as the official documents that are accesible online, only contain information about the Action Plan COVID-19 without mentioning the development of the crisis or the actual status. Regarding the offering of guidance, the government´s framing of the crisis was more successful as a lot of information is provided online on followed by the development of the CoronApp. The government under Sebastian Pinera also managed to instill hope at first, at least among some parts of the population, when looking at the part-time increase of approval-rates of the president. As mentioned before, Jaime Mañalich failed in his approach to demonstrate empathy with the people poorer districts of Santiago. But by using terms such as „us“ and „all chileans“ in public interviews and speeches, Pinera manages construct an unified image of the chilean society. Whether this corresponds to the reality is another question. But all in all, the president and his government managed to keep up the impression of being in control of the situation.

In the Chilean case, an explanation of what has happened is definitly missing, as the official documents that are accesible online, only contain information about the Action Plan COVID-19 without mentioning the development of the crisis or the actual status. Regarding the offering of guidance, the government´s framing of the crisis was more successful as a lot of information is provided online on followed by the development of the CoronApp. The government under Sebastian Pinera also managed to instill hope at first, at least among some parts of the population, when looking at the part-time increase of approval-rates of the president. As mentioned before, Jaime Mañalich failed in his approach to demonstrate empathy with the people poorer districts of Santiago. But by using terms such as „us“ and „all chileans“ in public interviews and speeches, Pinera manages construct an unified image of the chilean society. Whether this corresponds to the reality is another question. But all in all, the president and his government managed to keep up the impression of being in control of the situation.

6 Legitimacy

6.1 Legitimacy before the pandemic

Chile has experienced massive anti-government protests since the beginning of october where demonstrants called for social reforms and a new constitution, as the actual constitution is a heritage of the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. On october 18, Pinera declared the state of catastrophe allowing 10.000 soldiers of the military to go to the streets in order to take control of the situation [59] .

In order to beat down the protests, the „Carabineros“ (police officers in military uniform) as well as forces of the military used firearms, rubber bullets and tear gas even towards peaceful demonstrants[60] . There are over 2000 reports about sexualized violence and the abuse of arrested persons additional to cases where demonstrants got murdered [61] .

It is clear to say that police powers have been exercised to the degree of human right violations, all tolerated by the Chilean government.

After the state of catastrophe has been annulled and an announcement of social reforms has been made, protests still didn´t stop as the violent and brutal behavior towards the citizens created new anger and frustration[62] . As a result, a lot of demonstrants called for the resignation of president Pinera, having an approval rating below ten percent at that time (ibid.).

In order to beat down the protests, the „Carabineros“ (police officers in military uniform) as well as forces of the military used firearms, rubber bullets and tear gas even towards peaceful demonstrants[60] . There are over 2000 reports about sexualized violence and the abuse of arrested persons additional to cases where demonstrants got murdered [61] .

It is clear to say that police powers have been exercised to the degree of human right violations, all tolerated by the Chilean government.

After the state of catastrophe has been annulled and an announcement of social reforms has been made, protests still didn´t stop as the violent and brutal behavior towards the citizens created new anger and frustration[62] . As a result, a lot of demonstrants called for the resignation of president Pinera, having an approval rating below ten percent at that time (ibid.).

6.2 The State Fragility Index

On the website of the State Fragility Index, Chile is listed as one of the countries with a high degree of confidence, which means it is believed to be among the most worsened countries in 2020 according to the Index[63] .

Despite a generally imporving trend since 2012, Chile had to face different challenges in the last year. The growth of the economy slowed down followed by increasing economic instability, that in turn contributed to the dissatisfaction of the population. Together with systemic inequality, huge protests all over the country errupted. Another challenge that arose is the immigration of refugees from Venezuela (ibid.).

As the State Fragility Index also assesses countries in terms of their legitimacy, one can state that the Chilean government lost a lot of its legitimacy in the last year due to the violation of human rights and the downgrading economic conditions.

Despite a generally imporving trend since 2012, Chile had to face different challenges in the last year. The growth of the economy slowed down followed by increasing economic instability, that in turn contributed to the dissatisfaction of the population. Together with systemic inequality, huge protests all over the country errupted. Another challenge that arose is the immigration of refugees from Venezuela (ibid.).

As the State Fragility Index also assesses countries in terms of their legitimacy, one can state that the Chilean government lost a lot of its legitimacy in the last year due to the violation of human rights and the downgrading economic conditions.

6.3 Legitimacy during the crisis

Until late-april, the national strategy of implementing flexible lockdowns seemed to work, resulting in higher approval rates for the president, who fulfilled the role as leader by managing and limiting the negative effects of the crisis. Additional to that, the spread of COVID-19 put an end to the mass-demonstrations taking place in the streets [64] .

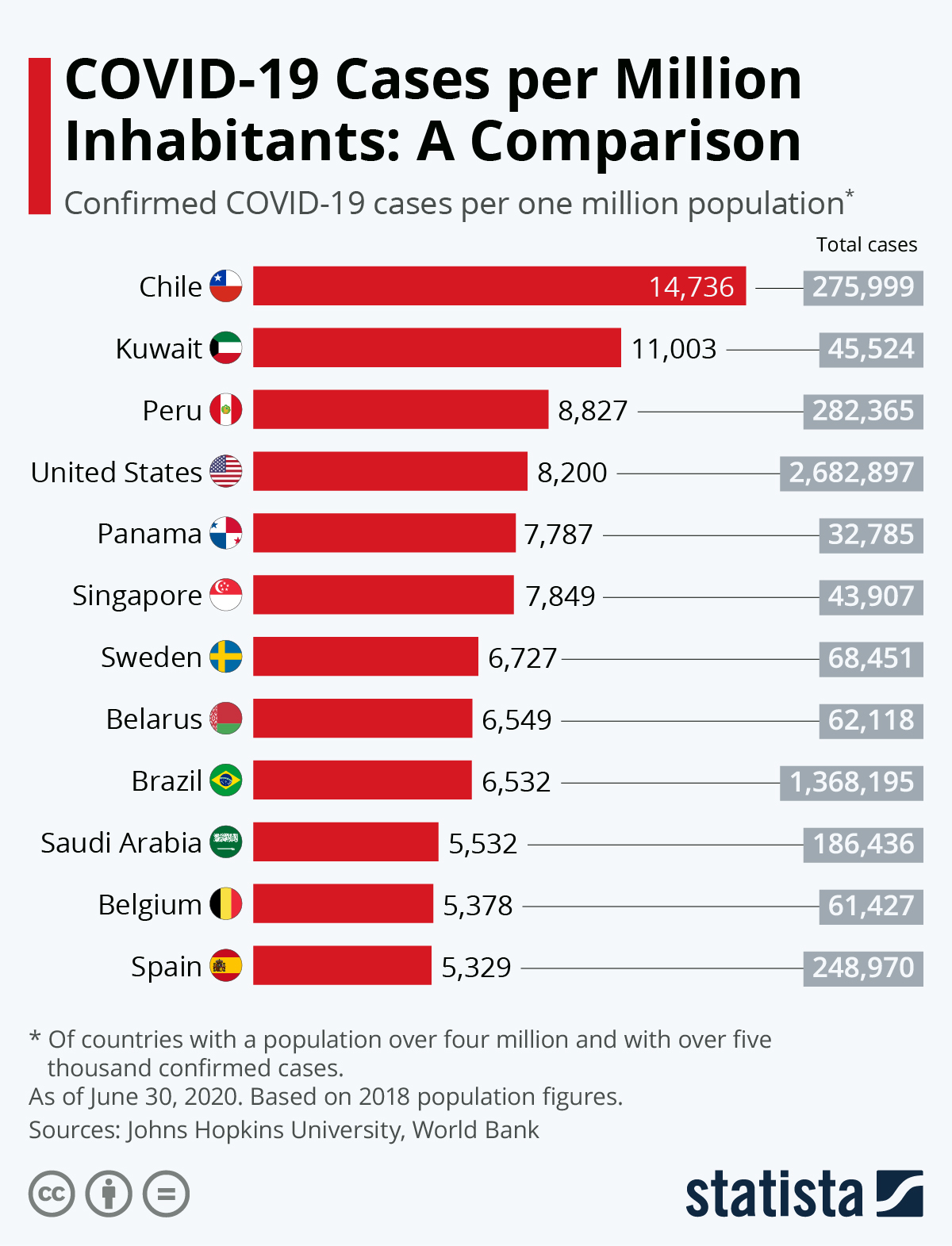

However, Chile had the highest proportional number of confirmed COVID-19 cases with a rate of 14.736 cases per one million inhabitants in june [65] . It became clear that the management of the crisis wasn´t as successful as the president pictured it.

One main reason for that was the ignorance towards experts and scientists who criticized the governmental approach already in march and april. Serious doubts of professionals were also voiced about the plans of implementing an immunity passport but the government undermined the expertise by implementing the release certificates [66] .

With the rising number of infections, critical voices of politicans, experts and social groups towards the health minister Jaime Mañalich and his handling of the crisis became louder. The last straw was a report that revealed that Mañalich had reported more cases of COVID-19 deaths to the WHO than he did to the public what underlines his lacking legitimacy. As a consequence, he has been replaced by the health professional Enrique Paris on June 13 [67] .

During may, protests demonstrating upset about the handling of the crisis by the governments emerged in poorer neighborhoods and began to spread and in the beginning of july, peaceful protests were ended by the police in a brutal way [68] . Just like in autumn, police officers follow the same pattern of repression.

However, Chile had the highest proportional number of confirmed COVID-19 cases with a rate of 14.736 cases per one million inhabitants in june [65] . It became clear that the management of the crisis wasn´t as successful as the president pictured it.

One main reason for that was the ignorance towards experts and scientists who criticized the governmental approach already in march and april. Serious doubts of professionals were also voiced about the plans of implementing an immunity passport but the government undermined the expertise by implementing the release certificates [66] .

With the rising number of infections, critical voices of politicans, experts and social groups towards the health minister Jaime Mañalich and his handling of the crisis became louder. The last straw was a report that revealed that Mañalich had reported more cases of COVID-19 deaths to the WHO than he did to the public what underlines his lacking legitimacy. As a consequence, he has been replaced by the health professional Enrique Paris on June 13 [67] .

During may, protests demonstrating upset about the handling of the crisis by the governments emerged in poorer neighborhoods and began to spread and in the beginning of july, peaceful protests were ended by the police in a brutal way [68] . Just like in autumn, police officers follow the same pattern of repression.

Comparison of cases per one million inhabitants as of June 30 (14)

6.4 Government Response Stringency Index

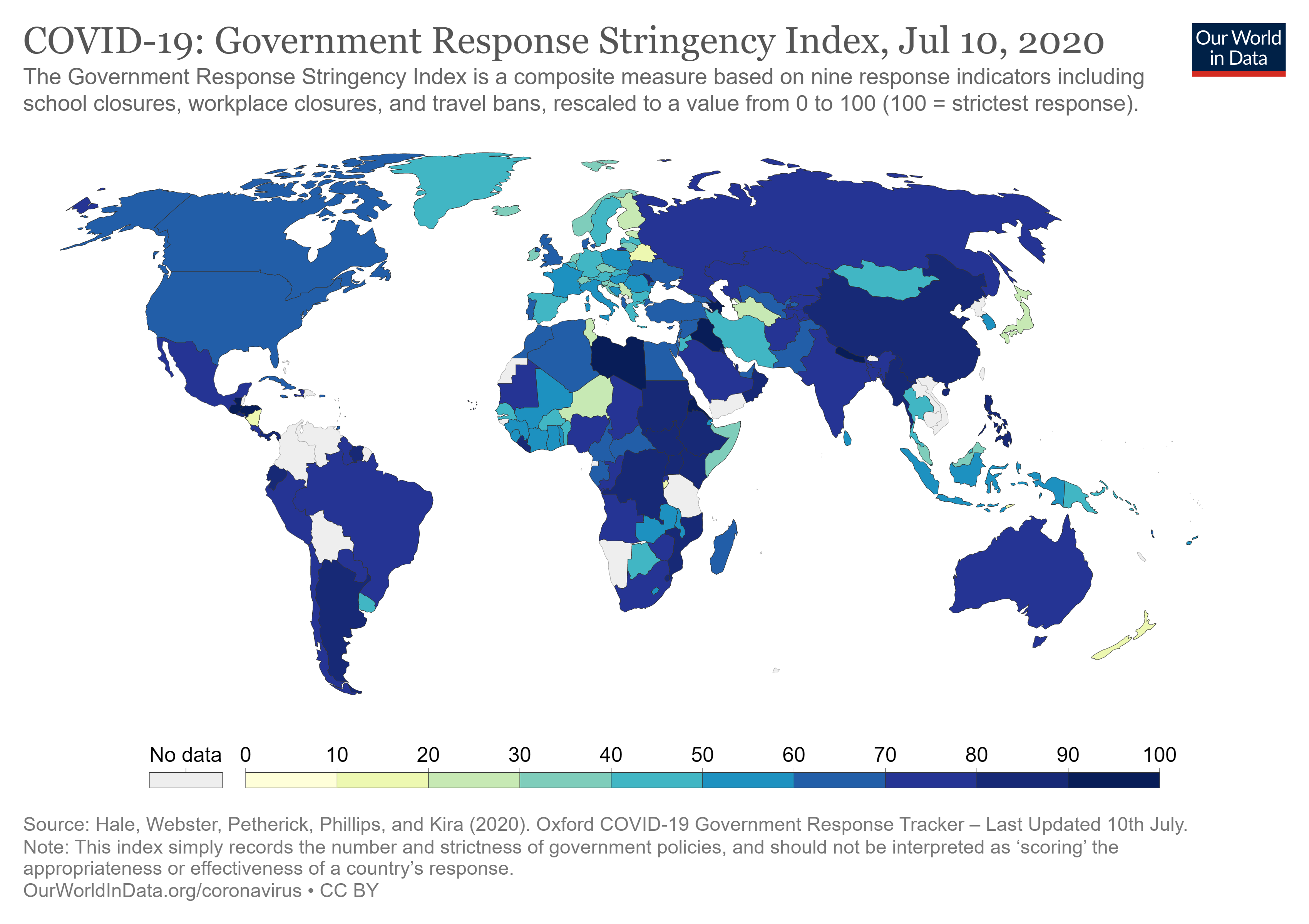

The Government Response Stringency Index assesses the amount of measures that have been implemented by a government in order to respond to the threat of the pandemic.

Even though Chile scores relatively high with 78.24 out of 100 (with 100 being the strictest response), the Index doesn´t incorporate thesuccess of the policy measures[69] . It definitly serves as an indicator for whether a country reacted at all, something we can´t deny in the case of Chile. Nevertheless, one should ask the question if policies could have been formulated better and implemented earlier if the government would have listened to experts sooner.

Even though Chile scores relatively high with 78.24 out of 100 (with 100 being the strictest response), the Index doesn´t incorporate thesuccess of the policy measures[69] . It definitly serves as an indicator for whether a country reacted at all, something we can´t deny in the case of Chile. Nevertheless, one should ask the question if policies could have been formulated better and implemented earlier if the government would have listened to experts sooner.

The Government Response Stringency Index (15)

6.5 Public perception of government actions

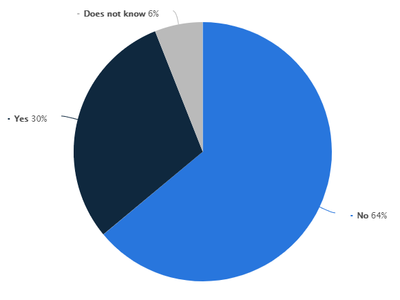

Do you agree the government has taken timely and appropriate decisions to address the novel COVID-19 crisis? (16)

As mentioned before, the Action Plan against COVID-19 published by the government contains statements about an early preparation in January and therefore seems like the extent of the crisis has been anticipated by those in power.

Meanwhile the population seems to think differently as shown in this survey that was conducted with 767 participants through an online panel, where 67% of the participants claim that the chilean government hasn´t taken timely and appropriate decisions in order to fight the coronavirus as of March 16.

Meanwhile the population seems to think differently as shown in this survey that was conducted with 767 participants through an online panel, where 67% of the participants claim that the chilean government hasn´t taken timely and appropriate decisions in order to fight the coronavirus as of March 16.

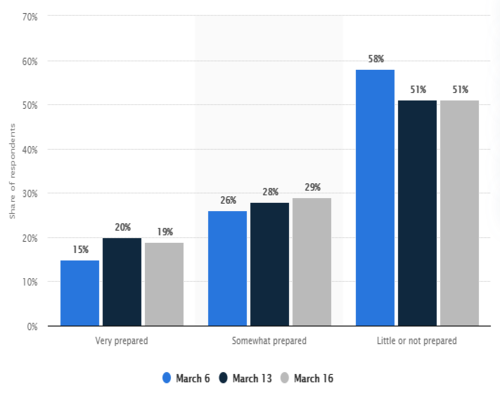

Perceptions on Chile's preparation to protect the population against COVID-19 as of March 16 2020 (17)

Results of another survery show that in March over 50% of the respondents perceived their country as little or not prepared in order to protect the population against COVID-19

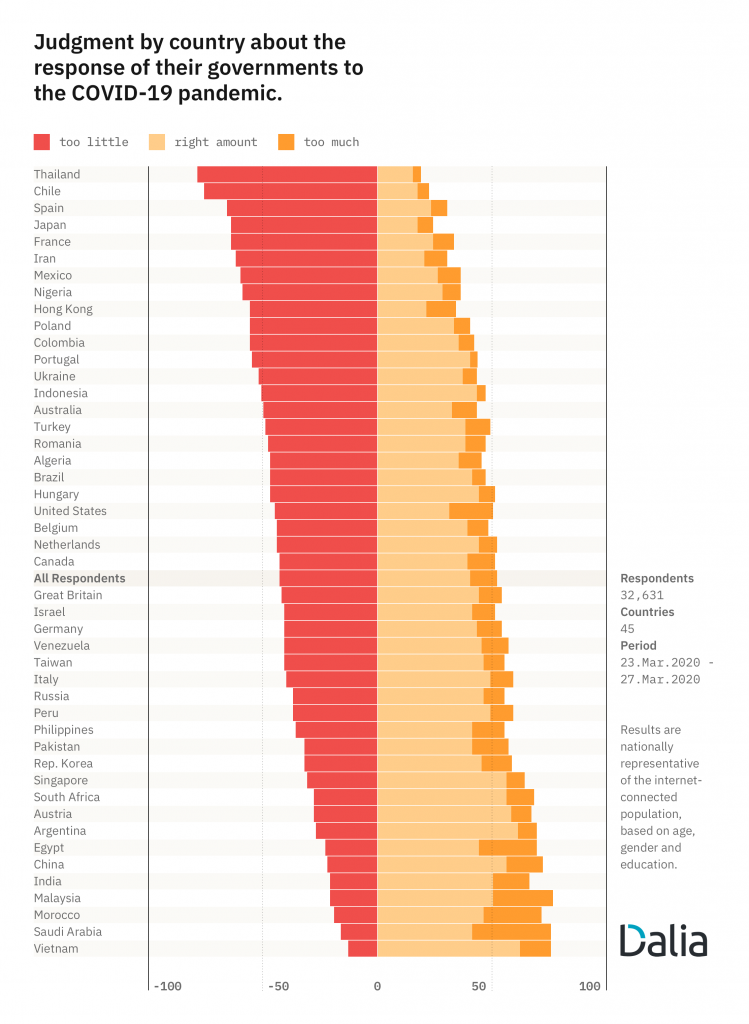

Evaluation of the response of their governments to the COVID-19 pandemic by country (18)

Research has also been done on the question “Think about your government’s reaction to COVID-19 (Coronavirus) right now. Do you believe measures taken are too much or too little?” asking 32.000 respondents in 45 countries all over the world. As a result, almost half (43%) of the citizens surveyed from march 23 to march 27 want more government action as reaction to the pandemic. In Chile, 76% of the respondents think that the government is doing too little as pictured in the graphic [70] .

Overall dissatisfaction with the government as in Chile can also be found in countries like France, Bulgaria and Thailand.

Overall dissatisfaction with the government as in Chile can also be found in countries like France, Bulgaria and Thailand.

7 Overall Evaluation

Boin et al. define the key concepts of a crisis as threat, urgency and uncertainty [71] . All conditions are fulfilled by the spread of the COVID-19 virus resulting in a global pandemic. When confronted with a crisis, people count on their leaders and governments to make sense out of the situation in order to protect the population and to limit the degree of damage [72] .

Back in march, president Piñera claimed that Chile was ready for the coronavirus and far better prepared than Italy. The amount of preparedness was underlined by the fast provisioning of additional hospital beds and ventilators as well as the announcement of the Action Plan COVID-19. By imposing flexible lockdowns and conducting a high amount of tests, it first seemed like the country´s approach against the crisis is successful. This appeared not to be true, as the infections continued to soar and more than 250.000 cases have been reported until the end of june. In terms of sense-making, the government didn´t perform that well, examples are the sudden addition of confirmed cases on June 18 and the concealing of COVID-19 related deaths. With over 315.000 confirmed cases as of today, Chile is on rank six worldwide [73] .

Because the virus first spread in the wealthier areas of Santiago where the private sector provides good health care for everyone who is able to afford it, officials considered the crisis as being under control. But similar to other countries like India, the outbreak of the virus sprawled from rich to poor people, as workers from poorer neighborhoods had no chance but go to work in order to support their families. To sum it up, the measures haven´t been adopted timely in relation to the development of the situation, the implementation of the dynamic lockdowns for example could have been conducted in a stricter way. Ximena Aguilera, epidemiologist and member of Chile´s coronavirus advisory committee, mentions that „(…) the strategy focused disproportionately on hospital care – when the social aspect is just as important.“ and thereby labels the segregation of the Chilean society as one of the main problems the country has to deal with [74] . The coronavirus mortality rate in the public hospitals of Santiago has been twice as high compard to the private clinics in the capital (ibid.) She continues by stating that “The panel of experts was only convened in March when the virus had already arrived in Chile, and the scientific community did not get its wish with regard to the data it wanted published. (...)" (ibid.).

The former health minister Dr Álvaro Erazo adds that "Health system capacity was not the problem in Chile (...). But our ability to handle the crisis has been negated by a lacklustre communications strategy that saw the government encourage people to go back to normal, all while the curve was soaring upwards.” [75]

In the ligth of old and new anti-government protests together with the bad performance of officials, such as the former health minister Mañalich, the government definitely suffers of lacking legitimacy.

Although a comparatively high number of tests is still being conducted, the chaotic and unclear communication towards the population, the ignorance towards the marginalized part of the population, the overconfidence after the first successfully imposed lockdowns and the delayed consultation of health experts lead to the conclusion that the crisis response of the Chilean government is neither inclusive nor prevented big parts of the population from suffering from an infection or other consequences of the pandemic such as redundancy. Nevertheless, the government performed the role of a decision-making and coordination instance by imposing different internationally approved measures, such as the mandatory wearing of a mask in public transportation or the closure of schools.

However, with a decreasing number of new confirmed cases per 5-day-average [76] it is likely that Chile has gone through the worst already. Whether the winter half year leads to a new increase of infections isn´t clear yet.

From my personal point of view, the crisis response of the Chilean government can be summarized as two-edged. On one hand, the government acknowledged its responsibility and implemented several measures in order to protect the population. But at the same time, a lot of people can´t afford high-quality health care and critical protests are beaten down, as the dimension of the pandemic emphasizes the immense societal cleavage and the unequal system anew. Out of personal experience and the research I have done for this entry, my impression of Chile is a country being governed by the rich for the rich.

For a better understanding of the impact of the crisis on the Chilean society, i would recommend reading the article Endstation Reichtum, written by Lisa Caspari, which can be found here https://www.zeit.de/wirtschaft/2017-06/chile-neoliberalismus-armutsgrenze-wirtschaft-reichtum.

Back in march, president Piñera claimed that Chile was ready for the coronavirus and far better prepared than Italy. The amount of preparedness was underlined by the fast provisioning of additional hospital beds and ventilators as well as the announcement of the Action Plan COVID-19. By imposing flexible lockdowns and conducting a high amount of tests, it first seemed like the country´s approach against the crisis is successful. This appeared not to be true, as the infections continued to soar and more than 250.000 cases have been reported until the end of june. In terms of sense-making, the government didn´t perform that well, examples are the sudden addition of confirmed cases on June 18 and the concealing of COVID-19 related deaths. With over 315.000 confirmed cases as of today, Chile is on rank six worldwide [73] .

Because the virus first spread in the wealthier areas of Santiago where the private sector provides good health care for everyone who is able to afford it, officials considered the crisis as being under control. But similar to other countries like India, the outbreak of the virus sprawled from rich to poor people, as workers from poorer neighborhoods had no chance but go to work in order to support their families. To sum it up, the measures haven´t been adopted timely in relation to the development of the situation, the implementation of the dynamic lockdowns for example could have been conducted in a stricter way. Ximena Aguilera, epidemiologist and member of Chile´s coronavirus advisory committee, mentions that „(…) the strategy focused disproportionately on hospital care – when the social aspect is just as important.“ and thereby labels the segregation of the Chilean society as one of the main problems the country has to deal with [74] . The coronavirus mortality rate in the public hospitals of Santiago has been twice as high compard to the private clinics in the capital (ibid.) She continues by stating that “The panel of experts was only convened in March when the virus had already arrived in Chile, and the scientific community did not get its wish with regard to the data it wanted published. (...)" (ibid.).

The former health minister Dr Álvaro Erazo adds that "Health system capacity was not the problem in Chile (...). But our ability to handle the crisis has been negated by a lacklustre communications strategy that saw the government encourage people to go back to normal, all while the curve was soaring upwards.” [75]

In the ligth of old and new anti-government protests together with the bad performance of officials, such as the former health minister Mañalich, the government definitely suffers of lacking legitimacy.

Although a comparatively high number of tests is still being conducted, the chaotic and unclear communication towards the population, the ignorance towards the marginalized part of the population, the overconfidence after the first successfully imposed lockdowns and the delayed consultation of health experts lead to the conclusion that the crisis response of the Chilean government is neither inclusive nor prevented big parts of the population from suffering from an infection or other consequences of the pandemic such as redundancy. Nevertheless, the government performed the role of a decision-making and coordination instance by imposing different internationally approved measures, such as the mandatory wearing of a mask in public transportation or the closure of schools.

However, with a decreasing number of new confirmed cases per 5-day-average [76] it is likely that Chile has gone through the worst already. Whether the winter half year leads to a new increase of infections isn´t clear yet.

From my personal point of view, the crisis response of the Chilean government can be summarized as two-edged. On one hand, the government acknowledged its responsibility and implemented several measures in order to protect the population. But at the same time, a lot of people can´t afford high-quality health care and critical protests are beaten down, as the dimension of the pandemic emphasizes the immense societal cleavage and the unequal system anew. Out of personal experience and the research I have done for this entry, my impression of Chile is a country being governed by the rich for the rich.

For a better understanding of the impact of the crisis on the Chilean society, i would recommend reading the article Endstation Reichtum, written by Lisa Caspari, which can be found here https://www.zeit.de/wirtschaft/2017-06/chile-neoliberalismus-armutsgrenze-wirtschaft-reichtum.

8 Country´s favoutrite stay at home song

9 Sources

- Graphics

- The GHS Index https://www.ghsindex.org/country/chile/ 06.20

- John Hopkins https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/new-cases07.20

- John Hopkins https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/cumulative-cases07.20

- Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/chile?country=~CHL07.20

- Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/chile?country=~CHL07.20

- John Hopkins University https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/international-comparison 20.06.20

- Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/1105907/latin-america-coronavirus-covid-19-tests-country/06.20

- Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-testing 01.07.20

- Action Plan Coronavirus https://cdn.digital.gob.cl/public_files/Campa%C3%B1as/Corona-Virus/documentos/2020.05.14_ADUANAS_SANITARIAS_ubicacion.pdf 07.20

- Action Plan Coronavirus https://www.gob.cl/coronavirus/plandeaccion/07.20

- Action Plan Coronavirus https://www.gob.cl/coronavirus/plandeaccion/07.20

- OECD http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-territorial-impact-of-covid-19-managing-the-crisis-across-levels-of-government-d3e314e1/06.20

- Chilean Government https://www.gob.cl/coronavirus/autocuidado/ 07.20

- Statista https://www.statista.com/chart/21176/covid-19-infection-density-in-countries-most-total-cases/07.20

- Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-stringency-index 10.07.20

- Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/1105130/chile-perceptions-government-response-against-coronavirus/06.20

- Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/1104794/chile-preparation-protection-against-coronavirus/06.20

- Dalia Research https://daliaresearch.com/blog/dalia-assesses-how-the-world-ranks-their-governments-response-to-covid-19/ 07.07.20

- Timeline

- Gobierno Digital https://digital.gob.cl/noticias/coronapp-la-nueva-aplicacion-de-chile-para-combatir-la-pandemia 05.07.20

- T13 https://www.t13.cl/noticia/nacional/carnet-covid-certificado-recuperados-requisitos-16-04-2020 05.07.20

- Chile as https://chile.as.com/chile/2020/05/15/tikitakas/1589544161_222643.html 05.07.20

- T13 https://www.t13.cl/noticia/nacional/chile-supero-china-contagios-covid-19-paises-mas-afectados-28-05-2020 05.07.20

- Departamento de Epidemiología https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/InformeEPI050720.pdf 05.07.20

- Contact Chile https://www.contactchile.cl/de/news/2020/06/30/covid-19:-aktuelle-situation-in-chile 05.07.20

[1] Boin, Arjen & Hart, Paul & Stern, Eric & Sundelius, Bengt. (2017). The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership Under Pressure

[2] Der neue Fischer Weltalmanach 2019, Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main 2018 10.06.20

[3] Süddeutsche Zeitung www.sueddeutsche.de, 10.06.20

[4] Human Development Report 2019, auf hdr.undp.org 10.06.20

[5] Die Zeit www.zeit.de, 27.06.2017

[6] Aljazeera, www.aljazeera.com, 18.03.2020

[7] Reuters.com, 18.03.2020

[8] ] Reuters.com, 15.06.2020

[9] Aljazeera.com 18.03.2020

[10] CHILE reports https://chilereports.cl/en/news/2020/04/03/health-ministry-has-3-300-mechanical-ventilators-available-for-the-covid-19-health-emergency 21.05.20

[11] The GHS Index https://www.ghsindex.org/about/ 22.06.2020

[12] Department of Epidemiology. 2018. “Illnesses of Obligatory Notification (Enfermedades de Notificacion Obligatoria)”. [ http://epi.minsal.cl/enfermedades-de-notificacion-obligatoria/ 27.06.20

[13] ChileCompra Mercado Publico. 2018. “Solicitation search (Busqueda licitacion). [ https://www.mercadopublico.cl/Home/BusquedaLicitacion ] 27.06.20

[14] Department of Epidemiology. 2018. “Public Health Vigilance Events (Vigilancia Eventos Salud Publica)”. [ http://epi.minsal.cl/vigilancia-eventos-salud-publica-2018/ ] 27.06.20

[15] World Health Organisation. 2018. “Disease outbreak news”. 2017 and 2018 pages. [ http://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/year/2018/en/ ]; [ http://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/year/2017/en/ ] 27.06.20

[16] Ministry of Interior and Public Safety. 2018. “Specific Plan for Emergencies of Variable Risk in Dangerous Materials (Plan Especifico por Variable de Riesgo Materiales Peligrosos)”. [ http://www.onemi.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/PEEVR_MATERIALES_PELIGROSOS_01-02-2018.pdf ] 27.06.20

[17] Ministry of Interior and Public Safety. 2018. “Chile Prepared (Chile Preparado)”. [ http://www.onemi.cl/simulacros/ ]27.06.20

[18]

Ministry of Interior and Public Safety. 2018. “Specific Plan for Emergencies of Variable Risk in Dangerous Materials”. [ http://www.onemi.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/PEEVR_MATERIALES_PELIGROSOS_01-02-2018.pdf ]. Accessed September 2018

Ministry of Interior and Public Safety. 2018. “Specific Plan for Emergencies of Variable Risk in Dangerous Materials”. [ http://www.onemi.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/PEEVR_MATERIALES_PELIGROSOS_01-02-2018.pdf ]. Accessed September 2018

[19] The Global Health Security Index https://www.ghsindex.org/country/netherlands/ 28.06.20

[20] The Global Health Security Index https://www.ghsindex.org/country/chile/ 28.06.20

[21] Institute of Public Health. 2018. “Institutional Development (Desarrollo Institucional)”. [ http://www.ispch.cl/quienes_somos/gestion_institucional ] 28.06.20

[22] Ministry of Education. “Professional Technical Education (Educacion Tecnico Profesional)”. [ http://www.tecnicoprofesional.mineduc.cl ] 28.06.20

[23] Ministry of Health. 2018. [ https://www.minsal.cl ] accessed November 2018

[24] Heinrich Böll Stiftung www.boell.de 10.09.2013

[25] GHS Index https://www.ghsindex.org/country/united-states/ 07.07.20

[26] John Hopkins University www.coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/new-cases 28.06.20

[27] John Hopkins University www.coronavirus.jhu.edu/data 13.07.20

[28] Our world in data https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/chile?country=~CHL 12.07.20

[29] La Tercera https://www.latercera.com/nacional/noticia/ministerio-de-salud-anuncia-cambio-de-metodologia-para-anunciar-cifras-de-fallecidos-por-covid-19/KQTLCRKPBRFLJDQHYBBNZGZCOM/ 06.07.20

[30] Bangkok Post https://www.bangkokpost.com/world/1938252/chile-reports-more-than-7-000-virus-deaths-under-new-counting-method 06.07.20

[31] The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/chile-coronavirus-lockdown-sebastian-pinera/2020/06/23/70e9701a-b4a7-11ea-aca5-ebb63d27e1ff_story.html 07.07.20

[32] John Hopkins University https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/international-comparison 28.06.20

[33] Action Plan COVID-19 https://www.gob.cl/coronavirus/plandeaccion/ 07.07.20

[34] https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/chile-coronavirus-lockdown-sebastian-pinera/2020/06/23/70e9701a-b4a7-11ea-aca5-ebb63d27e1ff_story.html 05.07.20

[35] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/chile-tightens-lockdowns-coronavirus-cases-surpass-200000-200617171310811.html 06.07.20

[36] Action Plan COVID-19 https://www.gob.cl/coronavirus/plandeaccion/ 05.07.20

[37] Action Plan COVID-19 https://www.gob.cl/coronavirus/plandeaccion/ 07.07.20

[38] Plan para enfrentar el Coronavirus https://cdn.digital.gob.cl/filer_public/17/1c/171c48f7-5f5c-4f04-aa72-2f5c731de6c9/declaracion_coronavirus_16mar20.pdf 06.07.20

[39] Action Plan COVID-19

https://www.gob.cl/coronavirus/plandeaccion/ 05.07.20

https://www.gob.cl/coronavirus/plandeaccion/ 05.07.20

[40] CHILE reports https://chilereports.cl/en/news/2020/04/28/health-ministry-s-advisory-committee-broadens-its-definition-of-suspected-and-confirmed-cases-of-covid-19 21.06.20

[41] The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/chile-coronavirus-immunity-passport-antibody-testing-card/2020/04/20/8daef326-826d-11ea-81a3-9690c9881111_story.html 06.07.20

[42] Corea Center for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a30402000000&bid=0030 11.07.20

[43] World Health Organisation https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/immunity-passports-in-the-context-of-covid-19 05.07.20

[44] T13 https://www.t13.cl/noticia/nacional/carnet-covid-certificado-recuperados-requisitos-16-04-2020 05.07.20

[45] Gobierno Digital https://digital.gob.cl/noticias/coronapp-la-nueva-aplicacion-de-chile-para-combatir-la-pandemia 05.07.20

[46] OECD http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-territorial-impact-of-covid-19-managing-the-crisis-across-levels-of-government-d3e314e1/ 28.06.20

[47] OECD http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-territorial-impact-of-covid-19-managing-the-crisis-across-levels-of-government-d3e314e1/ 28.06.20

[48] Basset, M. (2020), Just Because You Can Afford to Leave the City, Doesn’t Mean You Should, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/opinion/sunday/coronavirus-cities-density.html 27.06.20

[49] Government of Chile (2020), Mesa Social Covid-19, https://www.gob.cl/mesasocialcovid19/ 29.06.20