Brazil

Seitenübersicht

[Ausblenden]This wiki contribution is dealing with Brazil's state response to the ongoing global pandemic of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). COVID-19 is caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a novel coronavirus which has previously not been identified in humans. Initially, it was reported in Wuhan, China in mid-December 2019. Followed by international spread, it was declared a pandemic by the UN's World Health Organisation on March 11th. Brazil's (plus South America's) first case was reported on February 26th when a 61-year old man returning from Lombardy, Italy, was diagnosed positively to the virus. The COVID-19 pandemic is exposing Brazil to an unprecedented challenge. In March numbers skyrocketed, turning Brazil into one of the worst affected countries in the world, a global epicentre of the outbreak and the hardest-hit country in South America. Moreover, Brazil is the second most exposed country globally in numbers of confirmed cases and deaths. Having hit the 1 million case mark on June 19th, 2020, some even predict that Brazil could pass the US leading the highest caseload by August 2020 [1] [2] .

Besides this tremendous public health crisis, Brazil finds itself in far-reaching political insecurities, wherein the Brazilian government's highly ineffective and uncoordinated management of the COVID-19 pandemic has played a major role. The crisis displays itself in a highly polarized population and includes numerous disputes within the federal government and between federal and state governments about the strategy pursued in dealing with the disease as well as conflicts in the horizontal distribution of power between the branches of government. Brazil's president Jair Bolsonaro (65), who repeatedly trivialized the threat of the virus by declaring it a "small flu" and attending public anti-lockdown rallies, often without the wearing of a mask and the implementation of social distancing measures, was diagnosed positively for COVID-19 on Tuesday, 7th of July.

To assess Brazil's pandemic response, this Wiki analysis utilizes Boin et al.'s (2017) framework of "five critical tasks of strategic crisis leadership" [3] , namely sense making, decision making and coordinating, meaning making, accounting and learning as structural underpinnings for the analysis.

So far, the spread of the virus has not slowed down and the country is expected to slide yet into another recession. Because the task ends on July 14th, all events and developments beyond this date are regarded as irrelevant to the Wiki.

Besides this tremendous public health crisis, Brazil finds itself in far-reaching political insecurities, wherein the Brazilian government's highly ineffective and uncoordinated management of the COVID-19 pandemic has played a major role. The crisis displays itself in a highly polarized population and includes numerous disputes within the federal government and between federal and state governments about the strategy pursued in dealing with the disease as well as conflicts in the horizontal distribution of power between the branches of government. Brazil's president Jair Bolsonaro (65), who repeatedly trivialized the threat of the virus by declaring it a "small flu" and attending public anti-lockdown rallies, often without the wearing of a mask and the implementation of social distancing measures, was diagnosed positively for COVID-19 on Tuesday, 7th of July.

To assess Brazil's pandemic response, this Wiki analysis utilizes Boin et al.'s (2017) framework of "five critical tasks of strategic crisis leadership" [3] , namely sense making, decision making and coordinating, meaning making, accounting and learning as structural underpinnings for the analysis.

So far, the spread of the virus has not slowed down and the country is expected to slide yet into another recession. Because the task ends on July 14th, all events and developments beyond this date are regarded as irrelevant to the Wiki.

1 Introduction

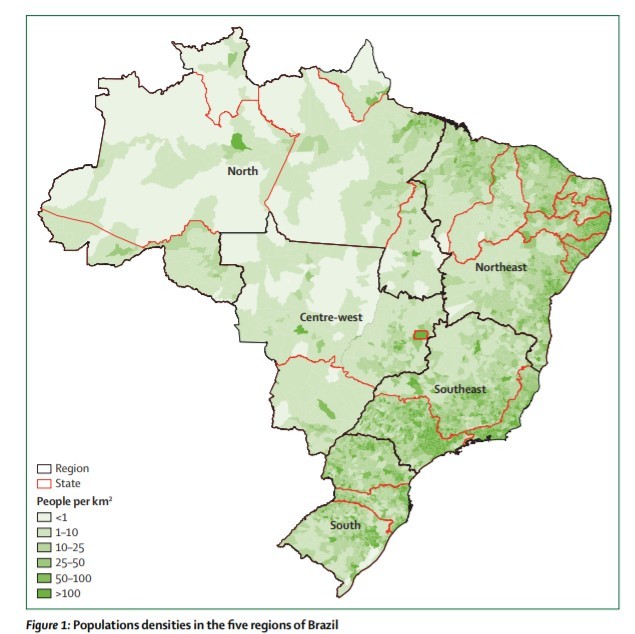

Figure 1; Brazil's regions and population density

Brazil (officially Federative Republic of Brazil or República Federativa do Brasil) is a country located in South America. It covers the continent’s half landmass and is the fifth largest country in the world by size [4] . Brazil shares borders with eight South American countries, precisely Uruguay, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and French Guyana. Its estimated population is 209, 712, 000 mio. (2019) ranking it the 6th most populous in 2018 and by far the most populous in South America [5] . The population is predominantly urban with Brazilians living in urban areas making off 86.6% relative to the total population and São Paulo being the most populated city in Brazil. Followed by Rio de Janeiro and Salvador, larger cities concentrate mostly along the eastern coastline (see Figure 1). Introduced by Portuguese colonialization, Portuguese is the Brazil's official language [6] .

Brazil's society is composed very heterogeneously as the country became a "melting pot" for a wide range of cultures during the centuries [cf. 1]. Major ethnic groups are Brazilians of European descent (or "white") (47.7%), mullattoes (mixed white and black) and mestizios (mixed European and Indian ancestry) (43.1%), there is a small amount of entirely African, Afro-Indian and Asian populations. Indians are the smallest ethnic group [7] . Uneven patterns of land ownership and extreme social inequalities remain major issues of the country in the 21st century [cf. 3]. Income inequality and poverty disproportionately affect the Northeast, North, and Center-West regions as well as women, the black, mixed-race, and indigenous populations. Brazil has relatively young demographics as the highest proportion of the population is between 15-54 years and about 9.2% are above 65 [cf. 6]. Furthermore, Brazil has a median age of 33.5 years which is considerably younger then especially East Asian and Western European G20 states averages [8] .

In the Human Development Index, which measures countries' progress and basic human development in three dimensions (long and healthy life, access to knowledge, decent standard of living) using several distinct indicators, Brazil positions 79 out of 189 countries and territories, trending positively since 1990 [9] . Even though referred to as a rapidly growing economic power and a state of the Bric-group (emerging economies with fast growth rates) in the first decade of the 21st century, Brazil went through a strong recession in the years 2015 and 2016 [10] . The economic recovery has been sluggish and economic growth in 2017 and 2018 did not exceed more than 1.1% a year, compared to 6.07% in 2007 [see World Bank Development Indicators]. In addition, Brazils' economy was negatively affected by numerous corruption scandals and public debt is among the highest in any emerging economy [11] . In terms of GDP per capita, Brazil in 2018 stands below the regional average with states such as Chile, Uruguay, Argentina, and Mexico outpassing it [see World Bank].

Brazil's society is composed very heterogeneously as the country became a "melting pot" for a wide range of cultures during the centuries [cf. 1]. Major ethnic groups are Brazilians of European descent (or "white") (47.7%), mullattoes (mixed white and black) and mestizios (mixed European and Indian ancestry) (43.1%), there is a small amount of entirely African, Afro-Indian and Asian populations. Indians are the smallest ethnic group [7] . Uneven patterns of land ownership and extreme social inequalities remain major issues of the country in the 21st century [cf. 3]. Income inequality and poverty disproportionately affect the Northeast, North, and Center-West regions as well as women, the black, mixed-race, and indigenous populations. Brazil has relatively young demographics as the highest proportion of the population is between 15-54 years and about 9.2% are above 65 [cf. 6]. Furthermore, Brazil has a median age of 33.5 years which is considerably younger then especially East Asian and Western European G20 states averages [8] .

In the Human Development Index, which measures countries' progress and basic human development in three dimensions (long and healthy life, access to knowledge, decent standard of living) using several distinct indicators, Brazil positions 79 out of 189 countries and territories, trending positively since 1990 [9] . Even though referred to as a rapidly growing economic power and a state of the Bric-group (emerging economies with fast growth rates) in the first decade of the 21st century, Brazil went through a strong recession in the years 2015 and 2016 [10] . The economic recovery has been sluggish and economic growth in 2017 and 2018 did not exceed more than 1.1% a year, compared to 6.07% in 2007 [see World Bank Development Indicators]. In addition, Brazils' economy was negatively affected by numerous corruption scandals and public debt is among the highest in any emerging economy [11] . In terms of GDP per capita, Brazil in 2018 stands below the regional average with states such as Chile, Uruguay, Argentina, and Mexico outpassing it [see World Bank].

1.1 The Political System of Brazil

Since the countries' coronacrisis response is accompanied by multiple political events with considerable significance and as there are voices claiming "the pandemic turned political in Brazil" [12], this section serves readers to gain a preliminary and rudimentary understanding of the Brazilian polity.

Brazil is a federal presidential republic, divided into 26 federal states plus the federal district including the capital city of Brasília. Its current constitution stems from 1988. The federal states are semi-autonomous entities, having their own constitutions, justice systems, directly elected governors and legislative assemblies. They are further subdivided into numerous municipalities. The bicameral National Congress (Congresso Nacional) represents the legislative branch of Brazils’ political system, consisting of the Chamber of Deputies (Câmara dos Deputados) and the Federal Senate (Senato Federal). While deputies are elected to the Chamber every four years, senators have an eight-year term of office to serve. Universal suffrage is exercised voluntarily between 16-18 years of age and compulsory between 18 and 70. Executive power is mainly exercised by the head of State and Government, which is President Jair Bolsonaro since 2019. The President is directly elected, serves a term of four years, and is eligible for one additional term. The president has a share of wide powers, including the appointing of ministers of state and several other heads of ministerial-level departments [13]. Under the 1988 constitution, "reactive" powers of the president involve a veto to legislation, which can be overridden by congress through an absolute majority and strong control over the budget. "Proactive" powers refer to Article 62, enabling presidents to implement "Provisional Measures" without congressional approval, "that have the force of law for a thirty-day period". Article 62 was explicitly designed for cases of "relevance and urgency", Mainwaring (1997) stresses, however, that "presidents have used Provisional Measures to push through all kinds of bills, with little concern for whether they truly constitute emergencies". In the same manner, presidents have considerable capacities to shape the congressional agenda: "if Congress fails to act on a presidential decree within 30 days, the Provisional Measure automatically goes to the top of the legislative agenda, displacing issues that the congress may have been discussing for some time" [14].

The judicial system comprises two branches: The ordinary branch, consisting of State and federal courts and a special branch with labour, electoral and military courts. The Supreme Federal Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal) is Brazil’s highest courts. It provides “final rulings on constitutional issues and hears cases involving the president, the vice president, Congress, the judiciary, the attorney general, government ministers, diplomats, foreign countries, and the political or administrative divisions of the union” [see Britannica].

Brazil is a federal presidential republic, divided into 26 federal states plus the federal district including the capital city of Brasília. Its current constitution stems from 1988. The federal states are semi-autonomous entities, having their own constitutions, justice systems, directly elected governors and legislative assemblies. They are further subdivided into numerous municipalities. The bicameral National Congress (Congresso Nacional) represents the legislative branch of Brazils’ political system, consisting of the Chamber of Deputies (Câmara dos Deputados) and the Federal Senate (Senato Federal). While deputies are elected to the Chamber every four years, senators have an eight-year term of office to serve. Universal suffrage is exercised voluntarily between 16-18 years of age and compulsory between 18 and 70. Executive power is mainly exercised by the head of State and Government, which is President Jair Bolsonaro since 2019. The President is directly elected, serves a term of four years, and is eligible for one additional term. The president has a share of wide powers, including the appointing of ministers of state and several other heads of ministerial-level departments [13]. Under the 1988 constitution, "reactive" powers of the president involve a veto to legislation, which can be overridden by congress through an absolute majority and strong control over the budget. "Proactive" powers refer to Article 62, enabling presidents to implement "Provisional Measures" without congressional approval, "that have the force of law for a thirty-day period". Article 62 was explicitly designed for cases of "relevance and urgency", Mainwaring (1997) stresses, however, that "presidents have used Provisional Measures to push through all kinds of bills, with little concern for whether they truly constitute emergencies". In the same manner, presidents have considerable capacities to shape the congressional agenda: "if Congress fails to act on a presidential decree within 30 days, the Provisional Measure automatically goes to the top of the legislative agenda, displacing issues that the congress may have been discussing for some time" [14].

The judicial system comprises two branches: The ordinary branch, consisting of State and federal courts and a special branch with labour, electoral and military courts. The Supreme Federal Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal) is Brazil’s highest courts. It provides “final rulings on constitutional issues and hears cases involving the president, the vice president, Congress, the judiciary, the attorney general, government ministers, diplomats, foreign countries, and the political or administrative divisions of the union” [see Britannica].

1.2 Political Situation prior to COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic hit Brazil amid the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro, who is portrayed as a far-right populist. Bolsonaro was elected president in the second round in October 2018 and took office on 1st January 2020. A self-claimed homophobe [12] and called a misogynist and racist by his opponents, Bolsonaro has regularly expressed his admiration and nostalgia for brazil's military dictatorship (1964-1985) (ibid.). Named "Trump of the tropics", Bolsonaro, a climate sceptic, is a deeply polarizing figure. He won the presidential election during heavy unemployment and after former president, Lula da Silva, was charged with corruption. Bolsonaro's predecessor Dilma Rousseff was impeached from office in 2016. Bolsonaro's power base is mostly seen in the evangelicals [13] and the military, with a considerable part of his cabinet consisting of former or on-duty military men [14] .

As a result of no clear political majorities for him in congress, leading to disputes between the legislative and executive branches, Brazil experiences both political stagnation and instability [15] . In economic terms, Brazil faced small GDP growth in 2019 fueling hopes that the country was about to leave its long-ranging previous recession [16] .

As a result of no clear political majorities for him in congress, leading to disputes between the legislative and executive branches, Brazil experiences both political stagnation and instability [15] . In economic terms, Brazil faced small GDP growth in 2019 fueling hopes that the country was about to leave its long-ranging previous recession [16] .

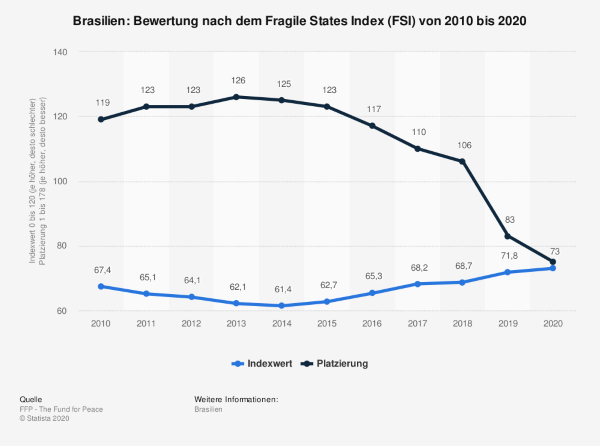

Figure 2, Brazil after the Fragile States Index

According to the Fragile States Index (previously Failed States Index, Figure 2) which measures countries' stability, Brazil has a value of 73 points [17] putting the country in the category of "Elevated Warning" regarding its vulnerability to conflict or collapse. It can be observed, that Brazil's negative trend since 2015 runs parallel to its economic development. As multiple nations develop negatively in the index, Brazil's downfall in terms of performance is not matched with a downfall in placement.

Meeting its nationally uncoordinated and diverging approach between federal and state-level governments of combatting COVID-19, the WHO lists Brazil under the category of no "National Plan for Pandemic Preparedness and Risk Management" that is publicly available in case of an virus outbreak [18] . Against this finding, the GHS index lists an "Epidemiological Surveillance Plan" for Brazil which establishes common procedures in case of pandemic diseases, such as influenza, cholera, or dengue and further plans for individual diseases [19] . However, there is absolutely no evidence whatsoever, that this plan was put into place or utilized for the COVID-19 pandemic. Brazil therefore highly contrasts from countries that followed precise epidemiological guidelines and scientific approaches in dealing with the new pandemic like Taiwan (https://ilias.uni-konstanz.de/ilias/goto.php?client_id=ilias_uni&target=wiki_1008389_Taiwan#ilPageTocA19 or South Korea https://ilias.uni-konstanz.de/ilias/goto.php?target=wiki_1008389_South_Korea].

I try to look at "Preparedness" from an angle of particular and unique preconditions to COVID-19 in Brazil. Thereby, aspects such as the healthcare system, GHS index, COVID-19 Regional Safety Assessment by Deep Knowledge Groupe, and political factors are regarded.

Above all other factors turning the novel coronavirus to a major global health challenge, such as little scientific knowledge, the fast pace of its spread, and its capacity to cause deaths in vulnerable groups the spread of COVID-19 in Brazil takes place in a context of huge social inequality. Precarious housing without access to running water and with widespread crowding fuels the disease's pace of transmission [20] . The circumstances for the adoption of different strategies of social distancing and its effects are therefore stated to be limited for Brazil (ibid.).

I try to look at "Preparedness" from an angle of particular and unique preconditions to COVID-19 in Brazil. Thereby, aspects such as the healthcare system, GHS index, COVID-19 Regional Safety Assessment by Deep Knowledge Groupe, and political factors are regarded.

Above all other factors turning the novel coronavirus to a major global health challenge, such as little scientific knowledge, the fast pace of its spread, and its capacity to cause deaths in vulnerable groups the spread of COVID-19 in Brazil takes place in a context of huge social inequality. Precarious housing without access to running water and with widespread crowding fuels the disease's pace of transmission [20] . The circumstances for the adoption of different strategies of social distancing and its effects are therefore stated to be limited for Brazil (ibid.).

1.3 Preconditions of the "Brazilian Case"

Shortly after the identification of the first case on Brazilian soil and before mass spreading of COVID-19 took place, scholars characterized the Brazilian healthcare system as "already fragile and vulnerable" and not sufficiently prepared for enduring a global pandemic. The social and economic issues in South America affecting the Health System previously were stressed, such as the political crisis in Venezuela causing migration linked to infectious diseases (for instance malaria) as further challenges. Concern was also raised about the adequate availability of intensive care units (ICU) and the availability of specific diagnosis tests (particularly the real-time PT-PCR) as crucial means for the detection of COVID-19 and the prevention of onward transmission. As the continent already suffers from dengue and measles, an epidemiological scenario called a "syndemic", that is the aggregation of two or more epidemics in a population, was named likely [21] .

Further factors exacerbate the Brazilian preconditions in case of a pandemic: Brazilian social heterogeneity raises the need for different medical and social management in each area. There is, due to the diversity of ethnicities and ancestral backgrounds, a high variability at the genome level, meaning that subpopulations share diverging genetic features. In this context, little is known about how genetic diversity leads to different phenotypic responses to COVID-19. Concerns were also raised about the indigenous population (ca. 500.000) as they have limited access to hospitals for intubation. This restriction of medical care, in particular, could lead to devastating outcomes for this part of the population.

Challenges profoundly involve housing as well, as it is crucial for the success of quarantine measures: The "great urban low-income conglomerates" [22] known as "Favelas" provide precarious living conditions with no or limited access to health, social, and financial support. Therefore "the infection can be transmitted and without diagnostic confirmation before or after death" in the Favelas. As people live closely together and share limited living space social distancing measures are almost impossible to adopt.

Another "Brazilian" challenge is the limited financial resources in terms of performing COVID-19 diagnosis and resources to deal with the disease at university hospitals, as support to research and scholarship was just recently cut [23] . Another area of uncertainty is the behaviour of the virus in a tropical climate: "Maybe, like other countries, Brazil may have a different severity and/or disease progression". According to Marson and Ortega (2020), Brazil lacks formal data on ICU beds and sub intensive care beds. Beds are further distributed between the private and public health systems with the demand of patients needing the public health system to be considerably higher. Following their estimation the number read as follows: The number of ICU beds is estimated between 60,000~62,000, for the most part, concentrated in three states: Sao Paulo (~18,000), Rio de Janeiro (~7,000) and Minas Gerais (~6,000). The number of beds is though not equally distributed across the country at the time of the estimation there was an occupancy rate of ~90%. Brazil has approximately 1 bed for every 10,000 citizens (WHO recommends 1-3). The quantity of respirators is also scarce, as ca. 65,000 respirators were estimated.

Another urgent issue is created by the size of the informal sector. About 40% of the working population works without a regular employment contract, which is about 38 million people [24] . In the event of pandemic measures that bring down public life, this part of the population is left without any income security or social protection. As these people depend on their day to day earnings shutdown measures affecting the economy would present a significant threat of imposing them to poverty and hunger.

Further factors exacerbate the Brazilian preconditions in case of a pandemic: Brazilian social heterogeneity raises the need for different medical and social management in each area. There is, due to the diversity of ethnicities and ancestral backgrounds, a high variability at the genome level, meaning that subpopulations share diverging genetic features. In this context, little is known about how genetic diversity leads to different phenotypic responses to COVID-19. Concerns were also raised about the indigenous population (ca. 500.000) as they have limited access to hospitals for intubation. This restriction of medical care, in particular, could lead to devastating outcomes for this part of the population.

Challenges profoundly involve housing as well, as it is crucial for the success of quarantine measures: The "great urban low-income conglomerates" [22] known as "Favelas" provide precarious living conditions with no or limited access to health, social, and financial support. Therefore "the infection can be transmitted and without diagnostic confirmation before or after death" in the Favelas. As people live closely together and share limited living space social distancing measures are almost impossible to adopt.

Another "Brazilian" challenge is the limited financial resources in terms of performing COVID-19 diagnosis and resources to deal with the disease at university hospitals, as support to research and scholarship was just recently cut [23] . Another area of uncertainty is the behaviour of the virus in a tropical climate: "Maybe, like other countries, Brazil may have a different severity and/or disease progression". According to Marson and Ortega (2020), Brazil lacks formal data on ICU beds and sub intensive care beds. Beds are further distributed between the private and public health systems with the demand of patients needing the public health system to be considerably higher. Following their estimation the number read as follows: The number of ICU beds is estimated between 60,000~62,000, for the most part, concentrated in three states: Sao Paulo (~18,000), Rio de Janeiro (~7,000) and Minas Gerais (~6,000). The number of beds is though not equally distributed across the country at the time of the estimation there was an occupancy rate of ~90%. Brazil has approximately 1 bed for every 10,000 citizens (WHO recommends 1-3). The quantity of respirators is also scarce, as ca. 65,000 respirators were estimated.

Another urgent issue is created by the size of the informal sector. About 40% of the working population works without a regular employment contract, which is about 38 million people [24] . In the event of pandemic measures that bring down public life, this part of the population is left without any income security or social protection. As these people depend on their day to day earnings shutdown measures affecting the economy would present a significant threat of imposing them to poverty and hunger.

1.4 Brazil's Healthcare System

The average life expectancy in Brazil in 2016 was 72.9 years for males and 79.4 years for females. After re-democratization, Brazil's 1988 constitution establishes health as a "fundamental right and responsibility of the state" [25] forming the basic principle of Brazil's health system. Brazils health system is forming a public-private mix and is subdivided into three parts: The public subsector (services provided and financed by the state at the federal, state and municipal levels), the private subsector (profit and non-profit), in which services are financed in various ways with public or private funds; and finally, the private health insurance subsector, based on different forms of health plans, varying insurance premiums and tax subsidies [26] . The health systems' public sector is organized around the Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS) and covers approximately 75% of the population (2011) [27] . Financing involves general taxes and social contributions collected by the three levels of government (federal, state, and municipal) (ibid.). The SUS provides health care through a decentralized network of clinics, hospitals, and other establishments. It aims to provide "comprehensive, universal preventive and curative care through decentralized management and provision of health services and promotes community participation at all administrative levels" and is free of charge. The public and private components of the system "are distinct and interconnected", people can use services in all three subsectors, mainly depending on their ability to pay. Therefore, public hospitals mainly serve poorer Brazilians and since the private sector is offering services on an out-of-pocket basis it is mostly used by the high-income population. Four-fifths of the hospitals in Brazil are public institutions and the largest share of doctors and hospitals concentrate in urban areas. This being, Brazil's widespread regional and social inequalities also show in the countries' health system as large disparities in health service coverage and access to healthcare persist.

Brazil's public health sector faces, in contrast to the private sector, numerous challenges such as low public funding due to austerity measures by the state and major deficits in equipment. In their 2018 paper "The Brazilian health system at crossroads: progress, crisis, and resilience" Massuda et al. find that "Economic recession and political crises pose a major threat to Universal Healthcare as well as long term austerity measures" as economic crises since 2014, accompanied by a sharp fall in GDP growth, lead to major cuts in health system financing, resulting in "inadequate financing" for public healthcare. Since 2015 there has been a reduction in the average per-capita funds allocated by municipalities to the UHS, "exacerbating historical underfunding and resource scarcity in the health system", and according to recent media reports leading to shortages of basic medicines, worsening working conditions for health professionals and shortages of doctors in public health facilities. They stressed further that Brazil has one of the lowest proportion of public spending on health (46.0%) in Latin America and the Caribbean (average 51.28%), in upper-middle-income countries (55.2%) and in OECD countries (62.2%). Several outbreaks of infectious diseases, such as yellow fever in 2016 and 18, the resurgence of syphilis, malaria, and dengue (with the highest recorded cases between 2016-18) and the emergence of new infectious diseases such as Chikungunya and Zika viruses have further put the Universal Healthcare System under pressure (cf .). Severe underfunding shows also in the number of hospital beds from 2010 to 2019 which has declined effectively from 2.28 beds per 1000 inhabitants to 1.95 in 2019 [28] .

Infectious diseases are a major public health issue for Brazil, despite the proportion of total deaths that are being caused decreasing tremendously [29] . The country is frequently hit by epidemics. In 2015 and 2016 the country found itself already in the epicentre of a large-scale virus outbreak, namely the Zika Virus, which was an epidemic of global concern. The mosquito-borne virus proved to have far-reaching consequences, especially for pregnant women, supposedly causing a serious birth defect in newborns known as microcephaly [30] . It was declared a "Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHIC) by the WHO. The main outbreak of the virus occurred simultaneously to the Olympic and Paralympic Games in Brazil. In May 2017, the Brazilian government ended its public health emergency on Zika. In the Zika case, Brazil was able to organize a large-scale response. However, since the Zika spread is different from COVID-19 and it affects other groups the outbreak serves as a poor basis of comparison.

There were successes and failures in the control of infectious diseases in Brazil. Barretto et al. (2011) state that handling of cholera, Chagas disease, and those "preventable by vaccination" has proved successful "through efficient public policies and concerted efforts from different levels of government and civil society". In those cases of infectious diseases, policies that improved key determinants such as the quality of water and basic sanitation provided access to preventive resources (such as vaccines), and "successfully integrated health policies with broader social policies" were effective. In their study, the authors examine measures taken in past spreadings of infectious diseases and aim to identify policies to further improve control or interrupt transmission. They point out that in Brazil's ongoing process of rapid urbanization, "cash transfer programs for the neediest populations, the SUS, and other social and environmental improvements (such as in sanitation and education) are crucial for efforts to control infectious diseases" in Brazil. From this conclusion can be derived again how poor housing conditions found in the major cities of the country contribute to the risks of a pandemic. Speaking of epidemics, at the time of the writing, the health care system registered about 2.2 million dengue fever infections, the highest count in the region.

Brazil's public health sector faces, in contrast to the private sector, numerous challenges such as low public funding due to austerity measures by the state and major deficits in equipment. In their 2018 paper "The Brazilian health system at crossroads: progress, crisis, and resilience" Massuda et al. find that "Economic recession and political crises pose a major threat to Universal Healthcare as well as long term austerity measures" as economic crises since 2014, accompanied by a sharp fall in GDP growth, lead to major cuts in health system financing, resulting in "inadequate financing" for public healthcare. Since 2015 there has been a reduction in the average per-capita funds allocated by municipalities to the UHS, "exacerbating historical underfunding and resource scarcity in the health system", and according to recent media reports leading to shortages of basic medicines, worsening working conditions for health professionals and shortages of doctors in public health facilities. They stressed further that Brazil has one of the lowest proportion of public spending on health (46.0%) in Latin America and the Caribbean (average 51.28%), in upper-middle-income countries (55.2%) and in OECD countries (62.2%). Several outbreaks of infectious diseases, such as yellow fever in 2016 and 18, the resurgence of syphilis, malaria, and dengue (with the highest recorded cases between 2016-18) and the emergence of new infectious diseases such as Chikungunya and Zika viruses have further put the Universal Healthcare System under pressure (cf .). Severe underfunding shows also in the number of hospital beds from 2010 to 2019 which has declined effectively from 2.28 beds per 1000 inhabitants to 1.95 in 2019 [28] .

Infectious diseases are a major public health issue for Brazil, despite the proportion of total deaths that are being caused decreasing tremendously [29] . The country is frequently hit by epidemics. In 2015 and 2016 the country found itself already in the epicentre of a large-scale virus outbreak, namely the Zika Virus, which was an epidemic of global concern. The mosquito-borne virus proved to have far-reaching consequences, especially for pregnant women, supposedly causing a serious birth defect in newborns known as microcephaly [30] . It was declared a "Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHIC) by the WHO. The main outbreak of the virus occurred simultaneously to the Olympic and Paralympic Games in Brazil. In May 2017, the Brazilian government ended its public health emergency on Zika. In the Zika case, Brazil was able to organize a large-scale response. However, since the Zika spread is different from COVID-19 and it affects other groups the outbreak serves as a poor basis of comparison.

There were successes and failures in the control of infectious diseases in Brazil. Barretto et al. (2011) state that handling of cholera, Chagas disease, and those "preventable by vaccination" has proved successful "through efficient public policies and concerted efforts from different levels of government and civil society". In those cases of infectious diseases, policies that improved key determinants such as the quality of water and basic sanitation provided access to preventive resources (such as vaccines), and "successfully integrated health policies with broader social policies" were effective. In their study, the authors examine measures taken in past spreadings of infectious diseases and aim to identify policies to further improve control or interrupt transmission. They point out that in Brazil's ongoing process of rapid urbanization, "cash transfer programs for the neediest populations, the SUS, and other social and environmental improvements (such as in sanitation and education) are crucial for efforts to control infectious diseases" in Brazil. From this conclusion can be derived again how poor housing conditions found in the major cities of the country contribute to the risks of a pandemic. Speaking of epidemics, at the time of the writing, the health care system registered about 2.2 million dengue fever infections, the highest count in the region.

Epidemiological legislation

Law no. 6.259, which was created before the unified health system (SUS), has been called the "main Brazilian standard for general epidemiological surveillance" [31] . Accordingly, the Brazilian Ministry of Health is responsible for coordinating and regulating measures to control diseases and health problems. The law provides for compulsory notification to health authorities of suspected or confirmed cases of diseases. Once notified, the health authority is obliged to carry out epidemiological investigations for instance on the spread of the disease) and to promptly adopt measures indicated for the control of the disease.

Brazil adopted the International Health Regulations, approved 2005 by the World Health Assembly. Therewith, Brazil assumed major international obligations in terms of health surveillance. 2011 the legal category of Public Health Emergency of National Importance was created. Two have been declared: the one related to Congenital Syndrome associated with infection by the Zika virus (CZS), between 2015 and 2017; and the one related to the new coronavirus (ibid.).

Law no. 6.259, which was created before the unified health system (SUS), has been called the "main Brazilian standard for general epidemiological surveillance" [31] . Accordingly, the Brazilian Ministry of Health is responsible for coordinating and regulating measures to control diseases and health problems. The law provides for compulsory notification to health authorities of suspected or confirmed cases of diseases. Once notified, the health authority is obliged to carry out epidemiological investigations for instance on the spread of the disease) and to promptly adopt measures indicated for the control of the disease.

Brazil adopted the International Health Regulations, approved 2005 by the World Health Assembly. Therewith, Brazil assumed major international obligations in terms of health surveillance. 2011 the legal category of Public Health Emergency of National Importance was created. Two have been declared: the one related to Congenital Syndrome associated with infection by the Zika virus (CZS), between 2015 and 2017; and the one related to the new coronavirus (ibid.).

1.5 Brazil's performance in the GHS Index

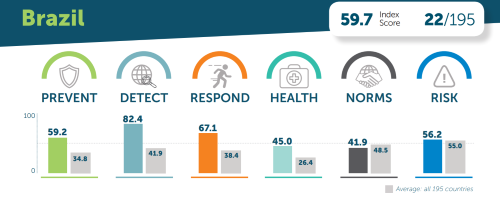

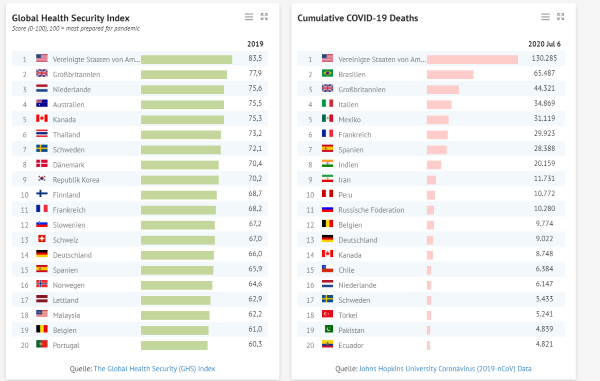

Figure 3; Relative performance to the average of 196 countries |  Figure 4; Overall Ranking |

In November 2019, the Global Health Security Index (GHS) was released by three leading research organizations: The Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (JHU), and the Economists Intelligence Unit (EIU). The goal of the GHS is to help understand and measure improvement in the global capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease threats [32] . It is assumed to be the first comprehensive assessment of global health security preparedness. Considering the fact that it directly estimates countries' preparedness for the emergence of deadly pathogens and epidemic or pandemic diseases, it establishes a valuable tool in studying pandemic preparedness. The GHS covers 195 countries and territories and is based on a comprehensive framework that comprises 140 questions organized around six categories: Prevention, Detection, and reporting, Rapid response, Health system, Compliance with international norms, and risk environment. It relies on open-source data. The United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands topped the global 2019 GHS ranking.

The GHS attempts to "illuminate preparedness and capacity gaps to increase both political will and financing to fill them" [33] .

Figure 3 shows how Brazil positions in comparison to the average of 196 included countries. Except for "health", measuring health care access and the sufficiency and robustness of the health system in treating the sick and protecting health workers, and "norms", indicating the willingness to improve national capacity, adhering to international norms and financing plans to address gaps, Brazil points above average in each category. In Figure 4, depicting Brazil in the upper third of all countries assessed, Brazil has been marked a "more prepared country".

Particularly striking, as it corresponds to observed reality is the placement of Brazil in the "risk"-category, covering the overall risk environment and country vulnerability to biological threats. There, Brazil performs especially bad in "Political and security risk" placing 70/195, "Socioeconomic resilicence" (101/196), and "public health vulnerabilities" (86/196). The "Socioeconomic resilience" indicator under the "Risk environment"-category covers among others poverty, "political and security risk" government effectiveness or risk of social unrest, and "public health vulnerabilities" access to potable water and sanitation as well as public health spending per capita.

However, the results of the Index must be enjoyed carefully in regard to the current COVID-19 pandemic. When comparing those countries that were supposed "most prepared" according to the index to actual data of COVID-19 cases and deaths, counterintuitively those occurring to be "prepared" appear to face particularly high caseloads and deaths. On April 7th, 12 of the 20th most prepared countries were in the top 20 globally for COVID-19 deaths. Consequently, analysts declare that the "Pandemic Preparedness Index itself is unprepared for COVID-19" [34] . Therefore, the organizations responsible for the index state that a countries' "score or rank do not indicate that the country is adequately prepared to respond to potentially catastrophic infectious disease outbreaks" and highlight the role of effective political leadership. This argument puts forward, that certain countries should have been able to respond in a better way to the Covid-19 health crisis than what they have done as they were, in theory, better prepared. In addition, it is told that "the COVID-19 pandemic has become a proof point for its main finding: national health security is fundamentally weak around the world." [35] .

The GHS attempts to "illuminate preparedness and capacity gaps to increase both political will and financing to fill them" [33] .

Figure 3 shows how Brazil positions in comparison to the average of 196 included countries. Except for "health", measuring health care access and the sufficiency and robustness of the health system in treating the sick and protecting health workers, and "norms", indicating the willingness to improve national capacity, adhering to international norms and financing plans to address gaps, Brazil points above average in each category. In Figure 4, depicting Brazil in the upper third of all countries assessed, Brazil has been marked a "more prepared country".

Particularly striking, as it corresponds to observed reality is the placement of Brazil in the "risk"-category, covering the overall risk environment and country vulnerability to biological threats. There, Brazil performs especially bad in "Political and security risk" placing 70/195, "Socioeconomic resilicence" (101/196), and "public health vulnerabilities" (86/196). The "Socioeconomic resilience" indicator under the "Risk environment"-category covers among others poverty, "political and security risk" government effectiveness or risk of social unrest, and "public health vulnerabilities" access to potable water and sanitation as well as public health spending per capita.

However, the results of the Index must be enjoyed carefully in regard to the current COVID-19 pandemic. When comparing those countries that were supposed "most prepared" according to the index to actual data of COVID-19 cases and deaths, counterintuitively those occurring to be "prepared" appear to face particularly high caseloads and deaths. On April 7th, 12 of the 20th most prepared countries were in the top 20 globally for COVID-19 deaths. Consequently, analysts declare that the "Pandemic Preparedness Index itself is unprepared for COVID-19" [34] . Therefore, the organizations responsible for the index state that a countries' "score or rank do not indicate that the country is adequately prepared to respond to potentially catastrophic infectious disease outbreaks" and highlight the role of effective political leadership. This argument puts forward, that certain countries should have been able to respond in a better way to the Covid-19 health crisis than what they have done as they were, in theory, better prepared. In addition, it is told that "the COVID-19 pandemic has become a proof point for its main finding: national health security is fundamentally weak around the world." [35] .

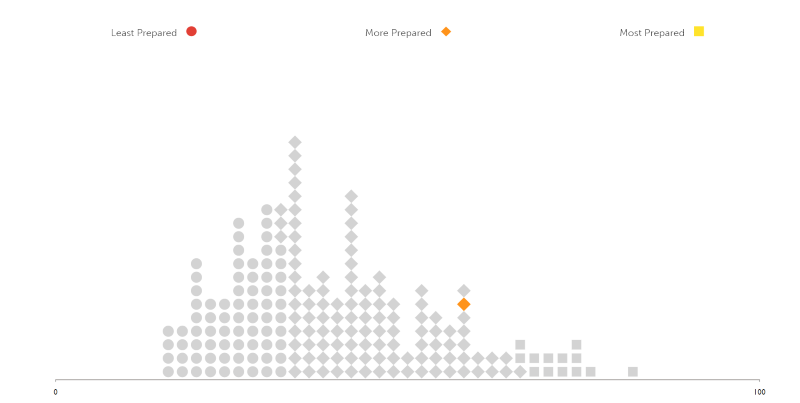

Figure 5; GHS index vs. cumulative deaths from COVID-19 by countries

As Figure 5 depicts, the pre-COVID-19 GHS index is if in no, in small association to countries' actual coronavirus outbreaks, which is explicitly presented in the cases of the US and the UK, which perform good on the GHS index but poor on COVID-19. Health systems supposed preparedness' and responses do accordingly not match, hinting at the GHS index greatly overestimating the capacity and preparedness of certain healthcare systems and underestimated others, such as Germany and South Korea which rank much better on evolving indices during COVID-19 [36] . Therefore, retrospectively, as the index stems from 2019, it is of little use and unmeaningful when reviewing countries' preparedness to COVID-19. Still, those factors going beyond the sheer health care system preparedness such as "Risk environment" are still valid, since they outline political and social risk factors in case of a pandemic outbreak and thus contribute to my goal of identifying particular Brazilian preconditions.

Additional country-level indices that measure countries' preparedness to face pandemics are the COVID-19 Safety-, Risk, and Treatment Efficiency Indices presented by Deep Knowledge Group, a consortium of profit and non-profit organizations and covering 150 countries by 72 metrics [37] . The Covid-19 safety index was produced after the initial outbreaks in March 2020 and remains preliminary and dynamic as the pandemic evolves. The “Safety” Index comprises "Quarantine efficiency", "Government management efficiency", "Monitoring and detection" and "Emergency treatment readiness". Although the results are preliminary, for the moment it is topped by Israel, Germany, and South Korea. Comparing both indices, there is no correlation in the GHS ranks and Covid-19 Safety ranks as it can be noted that the two top performers in the GHS – the United-Kingdom and United-States – are not in the top 40 performers in the Covid-19 Safety Index.

Additional country-level indices that measure countries' preparedness to face pandemics are the COVID-19 Safety-, Risk, and Treatment Efficiency Indices presented by Deep Knowledge Group, a consortium of profit and non-profit organizations and covering 150 countries by 72 metrics [37] . The Covid-19 safety index was produced after the initial outbreaks in March 2020 and remains preliminary and dynamic as the pandemic evolves. The “Safety” Index comprises "Quarantine efficiency", "Government management efficiency", "Monitoring and detection" and "Emergency treatment readiness". Although the results are preliminary, for the moment it is topped by Israel, Germany, and South Korea. Comparing both indices, there is no correlation in the GHS ranks and Covid-19 Safety ranks as it can be noted that the two top performers in the GHS – the United-Kingdom and United-States – are not in the top 40 performers in the Covid-19 Safety Index.

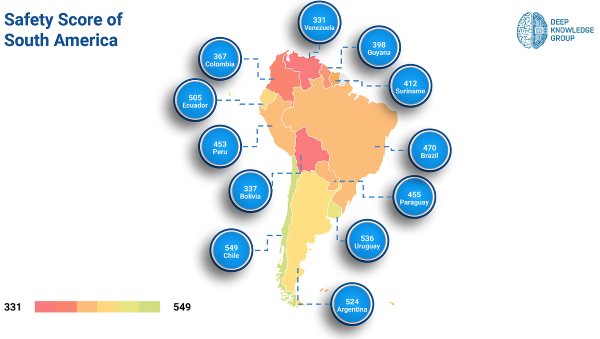

Figure 6; Safety Scores of South American countries |  Figure 7; detailed results for Brazil |

1.6 Brazil in the "COVID-19 Regional Safety Index"

In Deep Knowledge Groups "COVID-19 Regional Safety Index" Brazil is grouped in tier 3 ranking overall 91st place (of a total number of 200 countries ) by June 3rd with a cumulative score of 470 points, slightly higher than the regional South American average of 445 points but significantly lower than Chile (rank 41), Uruguay (51) or Argentina (62). The index is constructed around 60 parameters which are aggregated from each of the index's 6 categories ("COVID-19 Quarantine Efficiency", "COVID-19 Government Efficiency of Risk Management", "COVID-19 Monitoring and Detection", "COVID-19 Healthcare Readiness", "COVID-19 Regional Resiliency", "COVID-19 Emergency Preparedness"). Amongst the parameters are population density, number of cases, scale and scope of region-wide lockdown and length of quarantine or fines (under the category "Quarantine Efficiency"), the numbers of tests conducted per day and if the region has a significant shortage of COVID-19 tests ("COVID-19 monitoring and detection"), hospital beds and number of doctors ("Healthcare readiness"), literacy rate, poverty rate, size of the elderly population, and total transportation network size ("Regional resiliency"), government effectiveness, E-Government Development Index, number of internet users per 1000 ("Government Efficiency of Risk management"). The specific parameters for "Emergency preparedness" are not publicly disclosed.

For a more detailed look at the methodology I recommend using this link: http://analytics.dkv.global/covid-regional-assessment-200-regions/full-report.pdf

Figure 6 shows a broad variety of Regional Safety Scores for South America. Put into perspective Brazil's comparatively low score as the largest economy in Southern America, displayed in Figure 4, can be traced back to slow responses in lockdown measures. The result for those countries scoring significantly higher than average regional safety scores in South America (Chile, Uruguay, Peru, and Ecuador) is mainly attributed to very early, proactive government responses, specific policies and COVID-19 measures [38] and less to differences in healthcare modernization or development.

Figure 7 covers more detailed results for the Brazilian comparatively low score. "Monitoring and Detection", that is the scope of diagnostic methods, and testing efficiency is particularly weak as well as "Healthcare readiness" comprising COVID-19 equipment availability. "Government Efficiency and Risk Management", scoring 99 is lower than this of Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Ecuador. The category is made up of indicators such as rapid emergency mobilization, legislative effectiveness, and efficiency of Government structure.

What can be concluded from these results? According to the report, Tier 3 group in the study is made up of countries that scored significantly lower in cumulative regional safety scores in the analysis than expected given their general pre-pandemic levels of Quarantine Efficiency, Government Efficiency of Risk Management, Monitoring and Detection Efficiency, Health Readiness, Regional Resilience, and Emergency Preparedness [39] . Theoretically, given their healthcare, governmental, and crisis management capacities, these countries should have been prepared better, but in practice failed to pass the "stress test". This finding matches the GHS index in which Brazil was also classified as a "more prepared" country. Thus, the presumed reasons leading to scoring relatively low among South American countries and Tier 3 regions in the index are governmental strategies used to combat pandemics (ibid.). Resulting from this main hypothesis analyzing both indices that governmental strategies and policy factors play a crucial role in pandemic evolution in Brazil, I will set this as a special focus in my further analysis.

For a more detailed look at the methodology I recommend using this link: http://analytics.dkv.global/covid-regional-assessment-200-regions/full-report.pdf

Figure 6 shows a broad variety of Regional Safety Scores for South America. Put into perspective Brazil's comparatively low score as the largest economy in Southern America, displayed in Figure 4, can be traced back to slow responses in lockdown measures. The result for those countries scoring significantly higher than average regional safety scores in South America (Chile, Uruguay, Peru, and Ecuador) is mainly attributed to very early, proactive government responses, specific policies and COVID-19 measures [38] and less to differences in healthcare modernization or development.

Figure 7 covers more detailed results for the Brazilian comparatively low score. "Monitoring and Detection", that is the scope of diagnostic methods, and testing efficiency is particularly weak as well as "Healthcare readiness" comprising COVID-19 equipment availability. "Government Efficiency and Risk Management", scoring 99 is lower than this of Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Ecuador. The category is made up of indicators such as rapid emergency mobilization, legislative effectiveness, and efficiency of Government structure.

What can be concluded from these results? According to the report, Tier 3 group in the study is made up of countries that scored significantly lower in cumulative regional safety scores in the analysis than expected given their general pre-pandemic levels of Quarantine Efficiency, Government Efficiency of Risk Management, Monitoring and Detection Efficiency, Health Readiness, Regional Resilience, and Emergency Preparedness [39] . Theoretically, given their healthcare, governmental, and crisis management capacities, these countries should have been prepared better, but in practice failed to pass the "stress test". This finding matches the GHS index in which Brazil was also classified as a "more prepared" country. Thus, the presumed reasons leading to scoring relatively low among South American countries and Tier 3 regions in the index are governmental strategies used to combat pandemics (ibid.). Resulting from this main hypothesis analyzing both indices that governmental strategies and policy factors play a crucial role in pandemic evolution in Brazil, I will set this as a special focus in my further analysis.

1.7 Preparedness overall summary

As large disparities in Brazil's healthcare system persist and healthcare is unequally distributed in the country, Brazil's healthcare system is not resilient to a mass pandemic. Brazil's states do not possess the recommended counts of hospital beds with intensive treatment [40] and its health system is stressed already with infectious diseases. In addition to that, underfunding presents an urgent issue for the healthcare system. In recent times, there were numerous incidents unfolding around the catastrophic state of public hospitals [41] . Werneck et al. (2020) point out that "the COVID-19 pandemic has reached the Brazilian population in a scenario of extreme

vulnerability, with high unemployment rates and severe budget cuts in social policies."

Nearly half of the population is without regular employment and thus extremely vulnerable to the economic effects of quarantine measures. When there is a public shutdown, there wouldn't be any guaranteed income which they depend on in their work as housekeepers, street vendors, day laborers, etc [42] . As many as three-thirds of Brazilians live in cities and a great part in precarious housing conditions in low-income neighborhoods known as favelas, critically aggravating the adoption of social distancing measures. Little or no access to sanitation and a high population density present a surrounding where a highly contagious virus is very likely to spread quickly.

Brazil's indigenous communities are especially vulnerable. Brazil's current president has not turned out a special guardian of this population as he attempts to legalize commercial activities such as mining in the indigenous regions [43] Little is known about the immune response of the indigenous population to the virus and communities live often with precarious medical supply [44] . The political situation prior to the first cases in February and Bolsonaro's presidency was already heated. The country experienced years of economic recession and mass unemployment with no significant relaxation before COVID-19 [45] . These factors further weaken the country's stand and preconditions in times of a major health crisis.

vulnerability, with high unemployment rates and severe budget cuts in social policies."

Nearly half of the population is without regular employment and thus extremely vulnerable to the economic effects of quarantine measures. When there is a public shutdown, there wouldn't be any guaranteed income which they depend on in their work as housekeepers, street vendors, day laborers, etc [42] . As many as three-thirds of Brazilians live in cities and a great part in precarious housing conditions in low-income neighborhoods known as favelas, critically aggravating the adoption of social distancing measures. Little or no access to sanitation and a high population density present a surrounding where a highly contagious virus is very likely to spread quickly.

Brazil's indigenous communities are especially vulnerable. Brazil's current president has not turned out a special guardian of this population as he attempts to legalize commercial activities such as mining in the indigenous regions [43] Little is known about the immune response of the indigenous population to the virus and communities live often with precarious medical supply [44] . The political situation prior to the first cases in February and Bolsonaro's presidency was already heated. The country experienced years of economic recession and mass unemployment with no significant relaxation before COVID-19 [45] . These factors further weaken the country's stand and preconditions in times of a major health crisis.

2 Sense Making

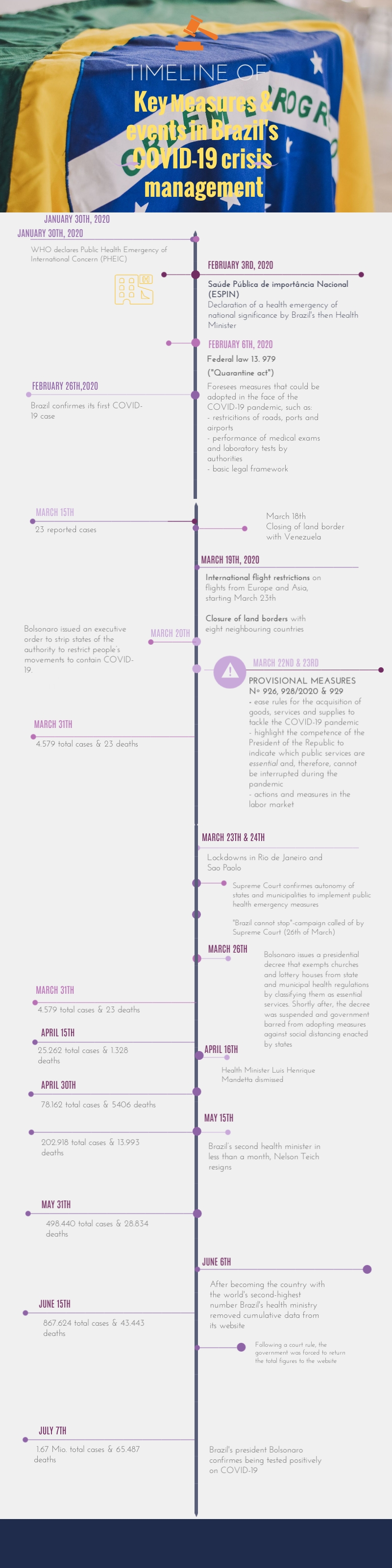

In the Boin et al. (2017) (cf. 1) crisis management framework, "Sense Making" is coined a "collecting and processing [of] information that will help crisis managers to detect an emerging crisis and understand the significance of what is going on during a crisis." Thus the following section will cover COVID-19 progression in Brazil using central figures and statistics.

Nonetheless, one has to be aware that COVID-19 statistics of Brazil are widely regarded as incomplete. It is assumed, that real statistics on cases and deaths are a lot higher as Brazil's testing is inadequate [46] . According to estimations, numbers could be as much as 7x-15x higher than officially reported and death rates twice as high [47] .

On June 06th/07th Brazil's Federal Government removed official statistics such as cumulative COVID-19 infection and death totals from the Health Ministry's website claiming sub-federal levels of government, such as municipalities and federal states inflated and over-reported numbers in order to gain federal funding [48] [49] . Also in early June, the daily presentation of figures was moved from afternoon to late in the evening. At this time former health minister Luis Henrique Mandetta called the actions and missing of public data on recognized epidemiological measures a "tragedy for the health system" (ibid.). After pressure rose from parliament and the Supreme Court's (Brazil's highest court) ruling that the Ministry must resume releasing all epidemiological data, a new website was set up (which can be accessed here: https://covid.saude.gov.br/) and the numbers were brought back [50] .

After the arrival of the virus and the first cases of the infection being registered among the higher social classes that travel internationally, COVID-19 was often coined a disease of the richer class. Soon however, due to living conditions and poverty which promote transmission, began to rage within the poorer parts of the population where it is believed to have far more damaging effects.

Nonetheless, one has to be aware that COVID-19 statistics of Brazil are widely regarded as incomplete. It is assumed, that real statistics on cases and deaths are a lot higher as Brazil's testing is inadequate [46] . According to estimations, numbers could be as much as 7x-15x higher than officially reported and death rates twice as high [47] .

On June 06th/07th Brazil's Federal Government removed official statistics such as cumulative COVID-19 infection and death totals from the Health Ministry's website claiming sub-federal levels of government, such as municipalities and federal states inflated and over-reported numbers in order to gain federal funding [48] [49] . Also in early June, the daily presentation of figures was moved from afternoon to late in the evening. At this time former health minister Luis Henrique Mandetta called the actions and missing of public data on recognized epidemiological measures a "tragedy for the health system" (ibid.). After pressure rose from parliament and the Supreme Court's (Brazil's highest court) ruling that the Ministry must resume releasing all epidemiological data, a new website was set up (which can be accessed here: https://covid.saude.gov.br/) and the numbers were brought back [50] .

After the arrival of the virus and the first cases of the infection being registered among the higher social classes that travel internationally, COVID-19 was often coined a disease of the richer class. Soon however, due to living conditions and poverty which promote transmission, began to rage within the poorer parts of the population where it is believed to have far more damaging effects.

2.1 COVID-19 Evolution in Brazil

On February 25, 2020, the Brazilian Ministry of Health confirmed its (supposedly) first COVID-19 case. The patient, a 61-year-old Brazilian man brought the disease from Lombardy in Northern Italy. The man was quickly isolated, received precautionary care and his contacts were traced. The premier Brazilian case is also considered the first (confirmed) COVID-19 case in South America. By June 29th, 2020, according to Johns Hopkins University (2020), 1.344.143 cases and 57.622 deaths of COVID-19 have been confirmed, ranking the country second behind the US [51] .

2.2 Tracking Cumulative Cases and New Infections

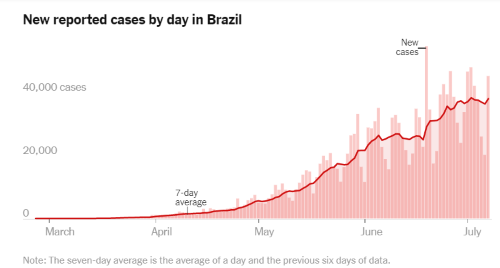

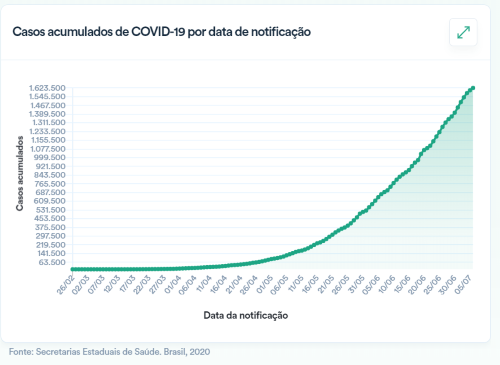

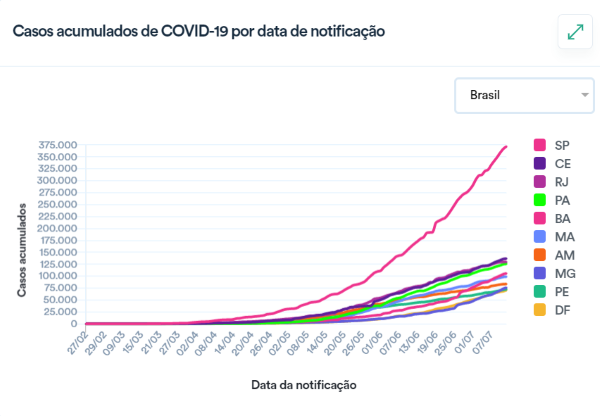

Figure 8; newly reported cases per day | Figure 9; cumulative cases by notification date |

Source: Brazil Coronavirus Map and Case Count By The New York Times (Updated July 8, 2020, 4:36 A.M. E.T.) |  Source: Painel de casos de doença pelo coronavírus 2019 (COVID-19) no Brasil pelo Minísteria da Saúde (Brazil Health Ministry Panel, see link above) |

Figure 8 depicts newly reported cases by day in Brazill as well as the seven-day average. From the time the first case was reported to the end of March (on 31.03., 1.138 new cases were reported and the 7-day average was at 502 cases) the curve remained relatively low. In April, rapid growth can be already observed: 1st of April saw 1.117 new cases and a 629 7-day average, while at the end of April (April 30th) newly reported cases rose at 7.502 and a 5.385 average. Comparing those values to the number of cumulative cases in Figure 9, by the beginning of May a cumulative total of cases of 91.604 was counted, as opposed to 5744 at the end of March.

In May 2020, the virus' spread in Brazil was further accelerated at accumulative case numbers enter the realm of six digits (101.227 cumulative confirmed cases on May 3rd). The number of recently identified cases reached a new height on May 30th, as 33.274 were newly tested positive for COVID-19 with a 7-day average of 21.477 who were positively tested the previous week. The rapid pace of COVID-19 spread can be further witnessed in June as total cumulative confirmed cases increase from 526.447 to almost one and a half million (1.402.041 cases on Jun 30th) within a month according to the ministry of health. June 19th saw a record-breaking figure of identified cases as they counted 54,771 and an almost 30.000 weekly average.

The New York Times counting method is either composed of a combination of confirmed cases and probable cases or the total of confirmed counts when they are available. Confirmed cases being "counts of individuals whose coronavirus infections were confirmed by a laboratory test.", probable cases counting "individuals who did not have a confirmed test but were evaluated using criteria developed by national and local governments". This alternative approach and the fact that authorities often revise data might explain why counts are somewhat different from the Ministry of Health's source on new cases per day.

Figure 9's cumulative confirmed cases show how the outbreak has expanded, counting every individual who has ever tested positive and paying no regard to whether a given individual has yet recovered. As an upward bend in the curve indicates a time of explosive growth in coronavirus cases, that the Brazilian curve has neither been flattened nor does it show any trend of decline. On the other hand it must be noted, that due to delays in reporting and to limited testing (as mentioned above) the actual number of cases is likely to be much higher than the number of confirmed cases.

In May 2020, the virus' spread in Brazil was further accelerated at accumulative case numbers enter the realm of six digits (101.227 cumulative confirmed cases on May 3rd). The number of recently identified cases reached a new height on May 30th, as 33.274 were newly tested positive for COVID-19 with a 7-day average of 21.477 who were positively tested the previous week. The rapid pace of COVID-19 spread can be further witnessed in June as total cumulative confirmed cases increase from 526.447 to almost one and a half million (1.402.041 cases on Jun 30th) within a month according to the ministry of health. June 19th saw a record-breaking figure of identified cases as they counted 54,771 and an almost 30.000 weekly average.

The New York Times counting method is either composed of a combination of confirmed cases and probable cases or the total of confirmed counts when they are available. Confirmed cases being "counts of individuals whose coronavirus infections were confirmed by a laboratory test.", probable cases counting "individuals who did not have a confirmed test but were evaluated using criteria developed by national and local governments". This alternative approach and the fact that authorities often revise data might explain why counts are somewhat different from the Ministry of Health's source on new cases per day.

Figure 9's cumulative confirmed cases show how the outbreak has expanded, counting every individual who has ever tested positive and paying no regard to whether a given individual has yet recovered. As an upward bend in the curve indicates a time of explosive growth in coronavirus cases, that the Brazilian curve has neither been flattened nor does it show any trend of decline. On the other hand it must be noted, that due to delays in reporting and to limited testing (as mentioned above) the actual number of cases is likely to be much higher than the number of confirmed cases.

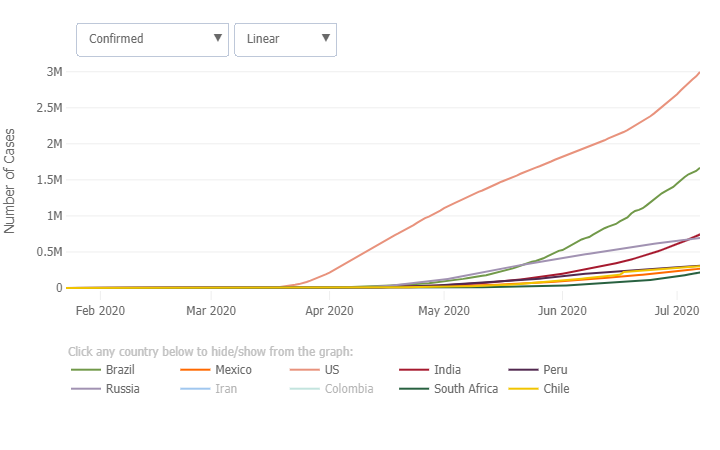

Figure 10; Cumulative Cases By Date

Putting these numbers into perspective by comparing across regions, I used the statistical tools presented by John Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center's to adjust for population [52] (for Figures 10 and 11).

On the right-hand side, the graph shows the cumulative confirmed number of cases by date. Selected countries compared to Brazil the US, India, Russia, Peru, Chile, and Mexico as they position amongst the premier 20 countries concerning COVID-19 cases. From the graph can be derived, how the virus spread in Brazil is even comparatively extended to other countries dealing with the outbreak. As it passed Russia by end of May Brazil became the country with the second-highest amount of total (confirmed) cases.

On the right-hand side, the graph shows the cumulative confirmed number of cases by date. Selected countries compared to Brazil the US, India, Russia, Peru, Chile, and Mexico as they position amongst the premier 20 countries concerning COVID-19 cases. From the graph can be derived, how the virus spread in Brazil is even comparatively extended to other countries dealing with the outbreak. As it passed Russia by end of May Brazil became the country with the second-highest amount of total (confirmed) cases.

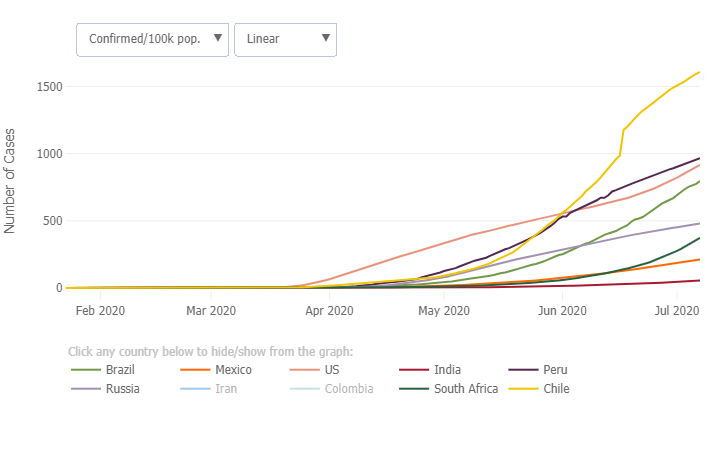

However, looking at the chart of Figure 11 underneath which assesses countries confirmed cases by date and 100.000 individuals, at least according to official statistics Chile, Peru, and the US have higher confirmed cases in relation to 100.000 population.

Figure 11; Cases per 100k population

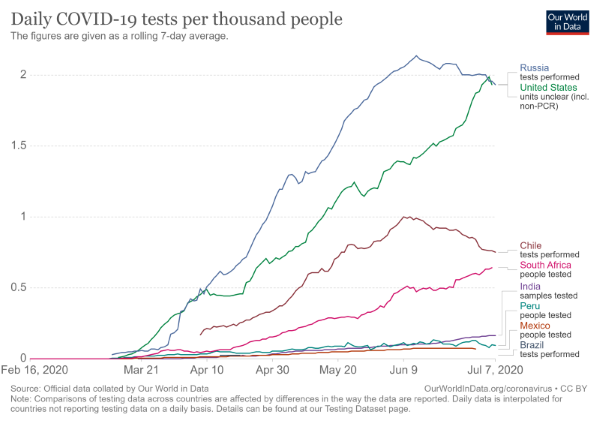

This result can be partly attributed to the testing that is carried out in countries. Figure 12 [53] shows that Brazil conducts considerably fewer tests than the countries previously compared to in relative caseload, meaning that these logically report more cases as they find more. Thus, following this logic and as already mentioned before, estimations expect high dark counts and unreported data for COVID-19 figures in Brazil due to little testing, leading to the assumption of likely even more critical circumstances.

Figure 12; COVID-19 Tests per Thousand People

2.3 Deaths and Mortality Rate

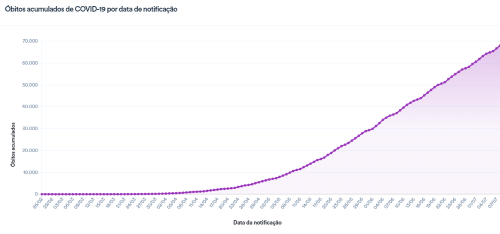

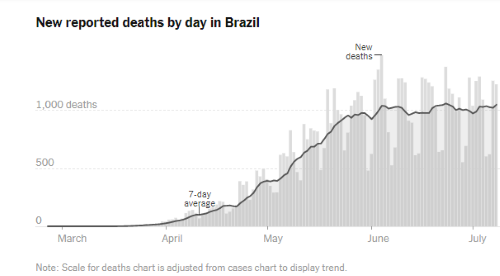

Figure 13; Brazil's number of COVID-19 deaths  | Figure 14; Brazil's reported COVID-19 related deaths by day  |

No progress has been made in bending the curve when one looks at the trends of deaths over time and daily reported deaths (Figure 13 & 14). On the contrary, the total numbers of deaths increase counting 60.632 deaths on July 1st. The numbers on newly reported deaths appear to constantly fluctuate around 1.000 and 1.200 cases per day since May displaying a clear upward trending. Here it must be also kept in mind, that the actual total death toll from COVID-19 is likely to be higher than the number of confirmed deaths.

Put in a nutshell, the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil is by no means controlled in Brazil and far from being so.

Put in a nutshell, the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil is by no means controlled in Brazil and far from being so.

2.4 Accounting for Brazilian interstate heterogeneity

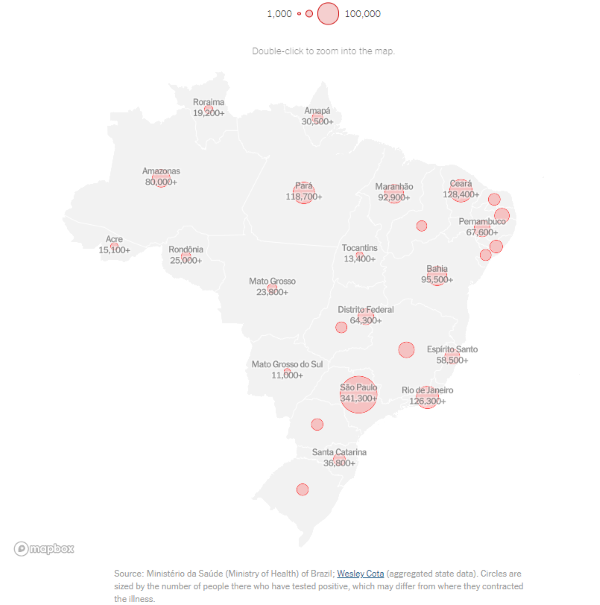

Source: Ministério da Saúde (Ministry of Health) of Brazil

Brazil is a country of continental dimensions and regional cultural, political, demographical, and economic variations persist between Brazil's states. Likewise, the regional epidemic intensity and dynamics differ. Scholars have already indicated that the characteristics of Brazilian states may significantly affect state epidemic dynamics, making them differ substantially [54] . These substantial differences feed "the need for optimal containment policies that are also heterogeneous and varying in extent and duration for different states." Borelli and Goes (2020) state that "disregarding the importance of such heterogeneities and not taking them into account to coordinate containment policies may amplify both the severity of the economic recession and the number of infected and deaths resulting from the epidemic."

Indeed there are great regional disparities in Brazil's COVID-19 outbreak. Brazil's most affected state is São Paulo, where the first South American case was reported, with 341.365 cases and 16.788 deaths on July 8th, 2020. The capitals of six federal states are centres of massive outbreaks: São Paulo (São Paulo), Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro), Fortaleza (Ceará), Belém (Pará), Manaus (Amazonas), and Recife (Pernambuco). Although regions of the North and Northeast count fewer total cases, they rely on a weaker public health system and some four states had already 90% of ICU bed capacity covered in early June. Medical resources are further unequally distributed as 17 out of 27 states fail to meet the benchmark of 1 ICU bed per 10.000 people [55]

Indeed there are great regional disparities in Brazil's COVID-19 outbreak. Brazil's most affected state is São Paulo, where the first South American case was reported, with 341.365 cases and 16.788 deaths on July 8th, 2020. The capitals of six federal states are centres of massive outbreaks: São Paulo (São Paulo), Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro), Fortaleza (Ceará), Belém (Pará), Manaus (Amazonas), and Recife (Pernambuco). Although regions of the North and Northeast count fewer total cases, they rely on a weaker public health system and some four states had already 90% of ICU bed capacity covered in early June. Medical resources are further unequally distributed as 17 out of 27 states fail to meet the benchmark of 1 ICU bed per 10.000 people [55]

Social Health Inequalities

Given that Brazil has a remarkably diverse population, a pandemic inevitably does not affect all parts of society in the same way. Instead, socioeconomic inequalities play a huge part in a pandemic development as there are particularly vulnerable populations [56] . Hence, next to regional health inequalities, social differences are an aspect necessarily to consider in an analysis. In Brazil, extreme disparities lead to Black Brazilians and Indigenous people getting sick and dying at much higher rates.

About a quarter of Brazilians have access to its private healthcare sector, mainly middle and high-income Brazilians. 51% of all ICU beds are allocated in private hospitals with Black and Pardo (mixed ethnicity) making up 15-20% of those covered by private health insurance plans. 67% of the public health system users identify as black.

Concerns about the virus' impact on the favelas were voiced, as mentioned before in Preparedness, already in advance. 1.5 Mio. mostly dark-skinned people alone living in Rio de Janeiro's favelas, the population is predominantly poor with some considerable amount living in precarious, crowded conditions without running water and health care access that is limited. A recent survey found already that due to the lack of reliable statistics the infection rate in the favelas could be as much as 30% higher [57] than the official count. There have been preliminary findings of an ethnicity effect on mortality with Pardo and Black populations being at higher risks when exposed to COVID-19 [58] .

Reports marked the devastating effect of COVID-19 on indigenous communities as well, a population heavily vulnerable when exposed to the virus. Historically speaking, imported diseases have often caused decimation among the indigenous population. As their living conditions make hygiene measures and social distancing considerably more difficult, many suffer from malnutrition and their medical care is precarious anyway, Brazilian 900.000 indigenous people face high death tolls and case number in face of the current pandemic. Some live that remoted, that hospitals are days away. Bolsonaro's government is harshly accused to have failed to protect the communities from the disease [59] . Several groups went into self-isolate by advancing deep into the forest. Under the rule of Bolsonaro, indigenous communities were already under severe threat. Brazil has dismantled environmental protections of the Amazon, allowing deforestation. Furthermore, there is an increase in an illegal land grab violating indegenous land rights.

About a quarter of Brazilians have access to its private healthcare sector, mainly middle and high-income Brazilians. 51% of all ICU beds are allocated in private hospitals with Black and Pardo (mixed ethnicity) making up 15-20% of those covered by private health insurance plans. 67% of the public health system users identify as black.

Concerns about the virus' impact on the favelas were voiced, as mentioned before in Preparedness, already in advance. 1.5 Mio. mostly dark-skinned people alone living in Rio de Janeiro's favelas, the population is predominantly poor with some considerable amount living in precarious, crowded conditions without running water and health care access that is limited. A recent survey found already that due to the lack of reliable statistics the infection rate in the favelas could be as much as 30% higher [57] than the official count. There have been preliminary findings of an ethnicity effect on mortality with Pardo and Black populations being at higher risks when exposed to COVID-19 [58] .

Reports marked the devastating effect of COVID-19 on indigenous communities as well, a population heavily vulnerable when exposed to the virus. Historically speaking, imported diseases have often caused decimation among the indigenous population. As their living conditions make hygiene measures and social distancing considerably more difficult, many suffer from malnutrition and their medical care is precarious anyway, Brazilian 900.000 indigenous people face high death tolls and case number in face of the current pandemic. Some live that remoted, that hospitals are days away. Bolsonaro's government is harshly accused to have failed to protect the communities from the disease [59] . Several groups went into self-isolate by advancing deep into the forest. Under the rule of Bolsonaro, indigenous communities were already under severe threat. Brazil has dismantled environmental protections of the Amazon, allowing deforestation. Furthermore, there is an increase in an illegal land grab violating indegenous land rights.

3 Decision-Making and coordination

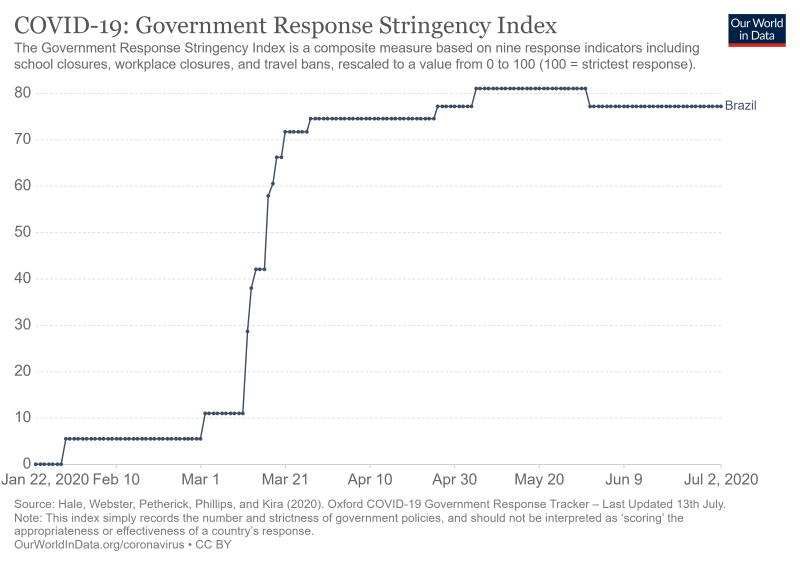

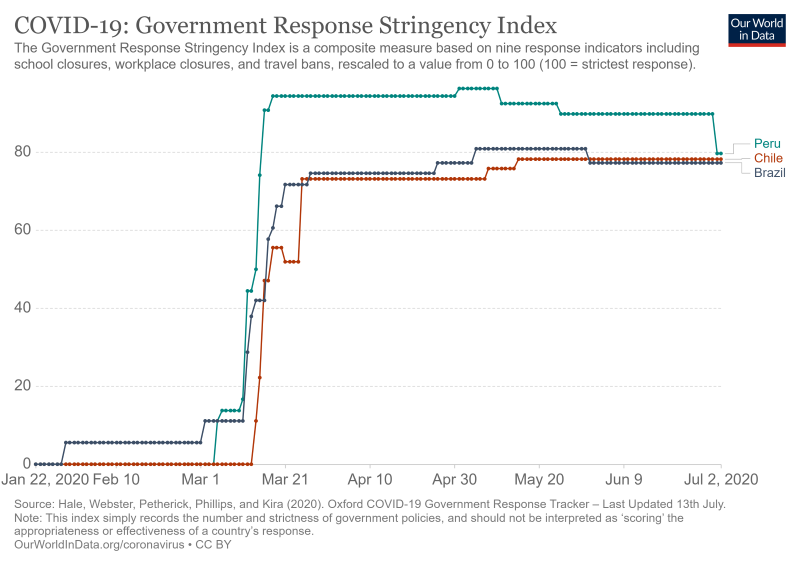

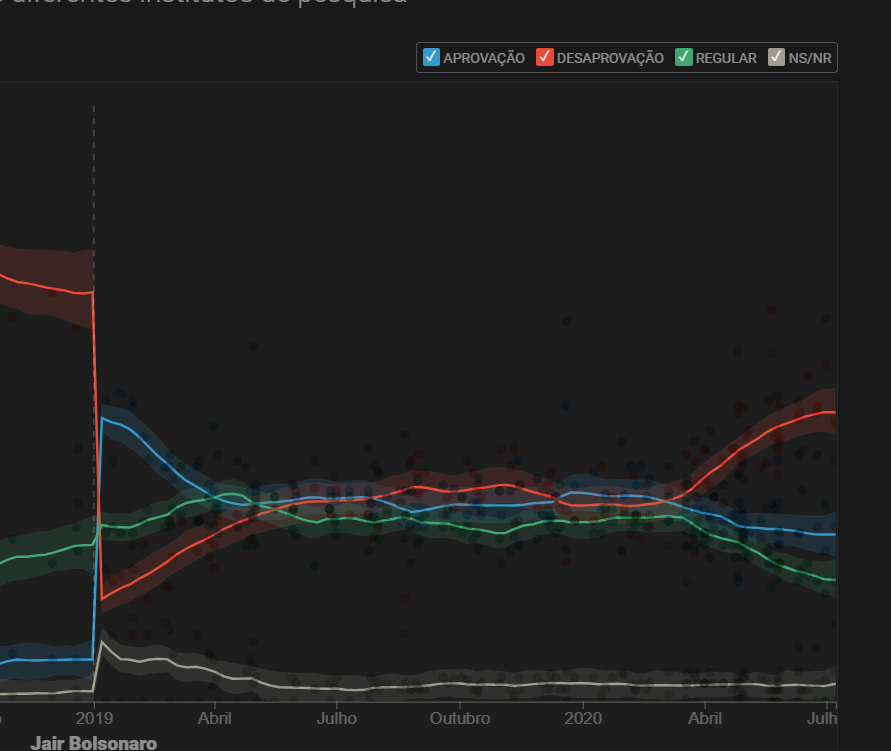

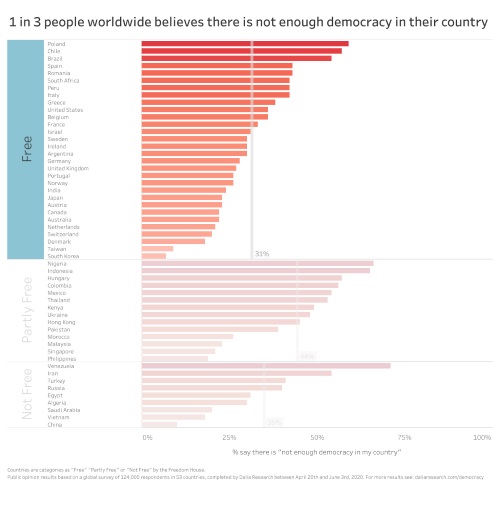

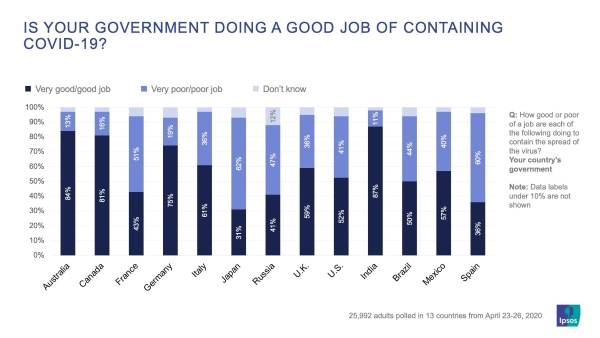

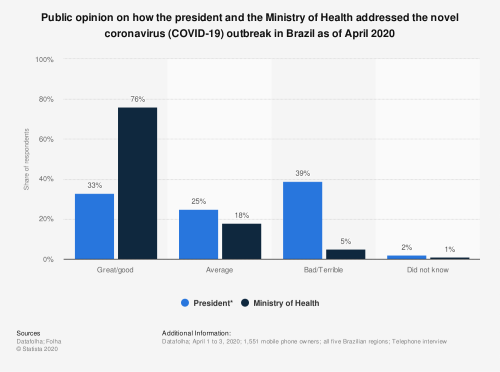

Boin et al. (2017) define decision-making as "making critical calls on strategic dilemmas and orchestrating a coherent response to implement those decisions.". Following the conclusion of the "Sense-Making" section that it hasn't been managed to bend the pandemic curve in Brazil and the COVID-19 outbreak being far from controlled, this part concerning "Decision-Making and Coordination" serves to trace measures which were adopted by political units and their timing in relation to the trends and dynamics of the pandemic.